So far, most of the Late Cretaceous fossils I have shared with you for Fossil Friday have been from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana and were collected over a number of years by the late Harley Garbani. The Hell Creek dates to the very end of the age of dinosaurs, just before the mass extinction 66 million years ago.There are more Hell Creek fossils at WSC to share, but today I want to showcase another fossil from a somewhat older slice of the Late Cretaceous. Last month, I showed you some plant fossils from our field area in New Mexico. Today's fossil is the tibia of a plant-eating dinosaur, probably a young hadrosaur, one of the duck-billed dinosaurs. This bone was found by University of Arizona - Tucson paleontology undergrad Kara Kelley and is now being prepared at WSC by volunteer Joe Reavis.This bone was collected from the Menefee Formation of New Mexico, and is around 80 million years old. We are now preparing and studying this bone and many other fossils collected by the Western Science Center, our partners at the Zuni Dinosaur Institute of Geosciences in Springerville, AZ, and volunteers from the Southwest Paleontological Society. We had a very successful expedition to the Menefee Formation in May-June; you can read an account of it written by yours truly. And we'll undertake another round of field work in the Menefee in August!Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

So far, most of the Late Cretaceous fossils I have shared with you for Fossil Friday have been from the Hell Creek Formation of Montana and were collected over a number of years by the late Harley Garbani. The Hell Creek dates to the very end of the age of dinosaurs, just before the mass extinction 66 million years ago.There are more Hell Creek fossils at WSC to share, but today I want to showcase another fossil from a somewhat older slice of the Late Cretaceous. Last month, I showed you some plant fossils from our field area in New Mexico. Today's fossil is the tibia of a plant-eating dinosaur, probably a young hadrosaur, one of the duck-billed dinosaurs. This bone was found by University of Arizona - Tucson paleontology undergrad Kara Kelley and is now being prepared at WSC by volunteer Joe Reavis.This bone was collected from the Menefee Formation of New Mexico, and is around 80 million years old. We are now preparing and studying this bone and many other fossils collected by the Western Science Center, our partners at the Zuni Dinosaur Institute of Geosciences in Springerville, AZ, and volunteers from the Southwest Paleontological Society. We had a very successful expedition to the Menefee Formation in May-June; you can read an account of it written by yours truly. And we'll undertake another round of field work in the Menefee in August!Post by Curator Dr. Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - Triceratops Teeth

Dinosaurs evolved many amazing and sophisticated adaptations during their long history. One of the most remarkable is the ability of some plant-eating dinosaurs to chew their food. This feature evolved independently in the armored ankylosaurs, the thumb-spiked and duck-billed iguanodonts, and the horned ceratopsians. In a recent open-access study, Erickson et al. (2015) examined the teeth of the famous ceratopsian Triceratops for clues as to how they functioned in feeding. This paper is available here: http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/1/5/e1500055.fullErickson et al. found that the teeth of Triceratops wore down to form a sharp cutting edge over time and with use, allowing the animal to chew resilient plants. As the teeth wore down, they also developed shallow depressions on the cutting surface as a means to lessen friction during the chewing motion. As a tooth was worn down completely, a new tooth growing from below would be ready to replace it.Today's Fossil Friday image shows two Triceratops teeth that were found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. Triceratops lived at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, and went extinct as part of the mass extinction 66 million years ago. These teeth show the sharp slicing edge along the top. Other Triceratops specimens discovered by Harley Garbani are on display in the Western Science Center's temporary exhibit Great Wonders: The Horned Dinosaurs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

Dinosaurs evolved many amazing and sophisticated adaptations during their long history. One of the most remarkable is the ability of some plant-eating dinosaurs to chew their food. This feature evolved independently in the armored ankylosaurs, the thumb-spiked and duck-billed iguanodonts, and the horned ceratopsians. In a recent open-access study, Erickson et al. (2015) examined the teeth of the famous ceratopsian Triceratops for clues as to how they functioned in feeding. This paper is available here: http://advances.sciencemag.org/content/1/5/e1500055.fullErickson et al. found that the teeth of Triceratops wore down to form a sharp cutting edge over time and with use, allowing the animal to chew resilient plants. As the teeth wore down, they also developed shallow depressions on the cutting surface as a means to lessen friction during the chewing motion. As a tooth was worn down completely, a new tooth growing from below would be ready to replace it.Today's Fossil Friday image shows two Triceratops teeth that were found in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana by local fossil hunter Harley Garbani and donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. Triceratops lived at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, and went extinct as part of the mass extinction 66 million years ago. These teeth show the sharp slicing edge along the top. Other Triceratops specimens discovered by Harley Garbani are on display in the Western Science Center's temporary exhibit Great Wonders: The Horned Dinosaurs.Post by Curator Dr. Andrew T. McDonald.

Fossil Friday - juvenile Tyrannosaurus

Tyrannosaurus rex. If any prehistoric animal has achieved mythic status among us humans, it must be this gigantic carnivorous dinosaur. But far from being a mere monster, T. rex was a living creature as complex, wondrous, and deserving of study as any alive today. As with many dinosaurs, the last two decades have seen a burst of new discoveries about T. rex, from the acuity of its senses to how it is related to other species in the tyrannosaur group. One of most fascinating areas of study is how T. rex grew.These formidable upper and lower jaws belong to an important part of that particular story. This is a cast of a specimen in the collection of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, LACM 28471. This cast belonged to the late fossil hunter Harley Garbani, who also found the actual fossil; the cast was donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. LACM 28471 was originally named as a new species of small tyrannosaur, called "Stygivenator molnari". However, in 2004, paleontologists Thomas Carr and Thomas Williamson showed that LACM 28471 is actually a juvenile specimen of T. rex.Juvenile specimens such as LACM 28471 reveal that young T. rex had much longer legs, lighter skulls, and longer snouts for their body size compared to adults. LACM has put the actual skull of LACM 28471 on display and mounted a cast skeleton (see photos), which you can see is much smaller than the adult looming overhead! A new discovery of a juvenile T. rex was just announced by paleontologists at the University of Kansas: http://news.ku.edu/2018/03/21/researchers-investigate-baby-tyrannosaur-fossil-unearthed-montana. There is still much for us to learn about the early life of the tyrant lizard king.

Tyrannosaurus rex. If any prehistoric animal has achieved mythic status among us humans, it must be this gigantic carnivorous dinosaur. But far from being a mere monster, T. rex was a living creature as complex, wondrous, and deserving of study as any alive today. As with many dinosaurs, the last two decades have seen a burst of new discoveries about T. rex, from the acuity of its senses to how it is related to other species in the tyrannosaur group. One of most fascinating areas of study is how T. rex grew.These formidable upper and lower jaws belong to an important part of that particular story. This is a cast of a specimen in the collection of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, LACM 28471. This cast belonged to the late fossil hunter Harley Garbani, who also found the actual fossil; the cast was donated to the Western Science Center by his wife, Mary. LACM 28471 was originally named as a new species of small tyrannosaur, called "Stygivenator molnari". However, in 2004, paleontologists Thomas Carr and Thomas Williamson showed that LACM 28471 is actually a juvenile specimen of T. rex.Juvenile specimens such as LACM 28471 reveal that young T. rex had much longer legs, lighter skulls, and longer snouts for their body size compared to adults. LACM has put the actual skull of LACM 28471 on display and mounted a cast skeleton (see photos), which you can see is much smaller than the adult looming overhead! A new discovery of a juvenile T. rex was just announced by paleontologists at the University of Kansas: http://news.ku.edu/2018/03/21/researchers-investigate-baby-tyrannosaur-fossil-unearthed-montana. There is still much for us to learn about the early life of the tyrant lizard king.

By Andrew McDonald

By Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - possible Leptoceratops tooth

If you follow the Western Science Center on social media, you have probably noticed that horned dinosaur fever has gripped the museum. We are gearing up for the March 24 opening of "Great Wonders: The Horned Dinosaurs", a new exhibit dedicated to the ceratopsians. The most famous ceratopsian must be Triceratops. Triceratops lived at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, right up to the mass extinction that wiped out all the dinosaurs (except modern birds) 66 million years ago.While elephant-sized Triceratops thundered across the American West, another, smaller type of ceratopsian scurried around at the same time. This dog-sized ceratopsian was called Leptoceratops. Here is an artist's depiction of this little dinosaur: http://images.dinosaurpictures.org/Leptoceratops-Peter-Trusler_036f.jpg. The object shown here is a possible tooth of Leptoceratops in the collections of the Western Science Center. It is tiny - the black and white squares on the scale bar next to the tooth are each only 1 centimeter long. This tooth was collected in a rock layer called the Hell Creek Formation, in Montana. It is one of many fossil discoveries made by the late Harley Garbani. We are now working to determine whether this tooth is Leptoceratops and, if so, whether it came from the upper or lower jaw.by Andrew McDonald

If you follow the Western Science Center on social media, you have probably noticed that horned dinosaur fever has gripped the museum. We are gearing up for the March 24 opening of "Great Wonders: The Horned Dinosaurs", a new exhibit dedicated to the ceratopsians. The most famous ceratopsian must be Triceratops. Triceratops lived at the very end of the age of dinosaurs, right up to the mass extinction that wiped out all the dinosaurs (except modern birds) 66 million years ago.While elephant-sized Triceratops thundered across the American West, another, smaller type of ceratopsian scurried around at the same time. This dog-sized ceratopsian was called Leptoceratops. Here is an artist's depiction of this little dinosaur: http://images.dinosaurpictures.org/Leptoceratops-Peter-Trusler_036f.jpg. The object shown here is a possible tooth of Leptoceratops in the collections of the Western Science Center. It is tiny - the black and white squares on the scale bar next to the tooth are each only 1 centimeter long. This tooth was collected in a rock layer called the Hell Creek Formation, in Montana. It is one of many fossil discoveries made by the late Harley Garbani. We are now working to determine whether this tooth is Leptoceratops and, if so, whether it came from the upper or lower jaw.by Andrew McDonald

Fossil Friday - ceratopsian rib

A few months ago Dr. Andrew McDonal joined the staff of WSC as our new curator. Andrew has been excavating for several years in the Cretaceous Menefee Formation on federal land in New Mexico, and now some of that material is making its way to WSC. This morning we opened our first Menefee Formation field jacket on public view at the museum’s Exploration Station. The image above shows the jacket after about 3 hours of prep work. The jacket contains a ceratopsian rib, the posterior edge of which is visible running through the middle of the jacket from the left end to about 10 cm past the top of the scale bar. The rib actually continues all the way to the other end of the jacket, but we’ve not yet uncovered it that far. The small black specks dotting the sediment are fragments of charcoal from burned Cretaceous trees.Andrew tells me that this rib is part of an associated skeleton including at least a dozen bones, from a small, probably juvenile, ceratopsian. So far we don’t know what taxon it represents, but there’s still a lot of material to prepare. This rib will be on public view in the Exploration Station for the next few weeks as we continue our preparation work.

A few months ago Dr. Andrew McDonal joined the staff of WSC as our new curator. Andrew has been excavating for several years in the Cretaceous Menefee Formation on federal land in New Mexico, and now some of that material is making its way to WSC. This morning we opened our first Menefee Formation field jacket on public view at the museum’s Exploration Station. The image above shows the jacket after about 3 hours of prep work. The jacket contains a ceratopsian rib, the posterior edge of which is visible running through the middle of the jacket from the left end to about 10 cm past the top of the scale bar. The rib actually continues all the way to the other end of the jacket, but we’ve not yet uncovered it that far. The small black specks dotting the sediment are fragments of charcoal from burned Cretaceous trees.Andrew tells me that this rib is part of an associated skeleton including at least a dozen bones, from a small, probably juvenile, ceratopsian. So far we don’t know what taxon it represents, but there’s still a lot of material to prepare. This rib will be on public view in the Exploration Station for the next few weeks as we continue our preparation work.

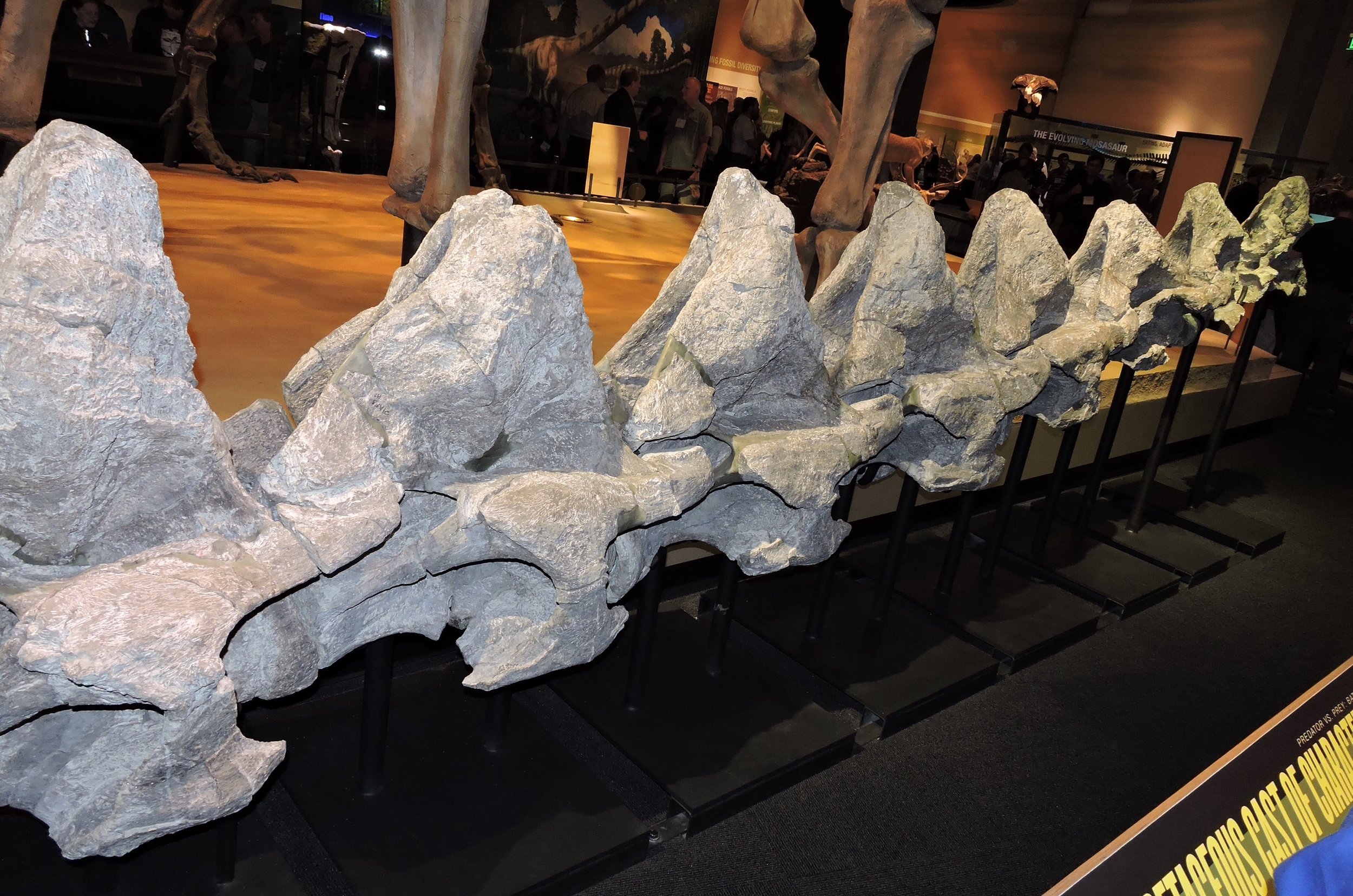

Fossil Friday - Alamosaurus neck vertebrae

This week I've been attending the annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP) meeting, which is being held this year in Dallas. SVP usually is held in a city with a natural history museum, and on Wednesday night the local museum will generally host a welcome reception. So for this week's Fossil Friday I photographed one of the highlights of the Perot Museum of Nature and Science's exhibits, the neck of Alamosaurus.Alamosaurus was a large sauropod dinosaur that has been found in Cretaceous sediments in the southwestern United States; this specimen is from Big Bend National Park in Texas. While not as famous as its older Jurassic relatives like Brontosaurus, Alamosaurus was just as large and impressive. This is easy to see when you realize that in the photo above you can only see 8 neck vertebrae!This image is taken as if you're standing near the base of the neck on the right side, looking forward, so the head would be toward the far right. There were at least a few more vertebrae at the base of the skull that were not preserved in this specimen, and more at the base of the neck as well. In fact, there is a ninth vertebra on exhibit, but the neck is so large that with the reception crowds I couldn't get far enough away to get all nine vertebrae in one photo from this angle. So here are all nine, looking from the front to the back:

This week I've been attending the annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP) meeting, which is being held this year in Dallas. SVP usually is held in a city with a natural history museum, and on Wednesday night the local museum will generally host a welcome reception. So for this week's Fossil Friday I photographed one of the highlights of the Perot Museum of Nature and Science's exhibits, the neck of Alamosaurus.Alamosaurus was a large sauropod dinosaur that has been found in Cretaceous sediments in the southwestern United States; this specimen is from Big Bend National Park in Texas. While not as famous as its older Jurassic relatives like Brontosaurus, Alamosaurus was just as large and impressive. This is easy to see when you realize that in the photo above you can only see 8 neck vertebrae!This image is taken as if you're standing near the base of the neck on the right side, looking forward, so the head would be toward the far right. There were at least a few more vertebrae at the base of the skull that were not preserved in this specimen, and more at the base of the neck as well. In fact, there is a ninth vertebra on exhibit, but the neck is so large that with the reception crowds I couldn't get far enough away to get all nine vertebrae in one photo from this angle. So here are all nine, looking from the front to the back:  The Perot Museum asked Research Casting International to produce a cast reconstruction of Alamosaurus based on these vertebrae and other Alamosaurus specimens. The cast is also on exhibit:

The Perot Museum asked Research Casting International to produce a cast reconstruction of Alamosaurus based on these vertebrae and other Alamosaurus specimens. The cast is also on exhibit: The people standing around the exhibit give an idea of scale. If that's not enough, that little theropod dinosaur standing beside Alamosaurus is Tyrannosaurus, and a Columbian mammoth is just visible at the lower left. By any standards, Alamosaurus was a huge animal!For more abut Alamosaurus, and to see photos of this specimen in the field, visit the SV-POW! blog.

The people standing around the exhibit give an idea of scale. If that's not enough, that little theropod dinosaur standing beside Alamosaurus is Tyrannosaurus, and a Columbian mammoth is just visible at the lower left. By any standards, Alamosaurus was a huge animal!For more abut Alamosaurus, and to see photos of this specimen in the field, visit the SV-POW! blog.

Fossil Friday - Tyrannosaurus tooth

The vast majority of the Western Science Center's fossil collection comes from Pleistocene deposits in Riverside County, so most of our specimens are less than 200,000 years old. Being so geologically young, birds are almost the only dinosaurs in our collection, as birds were the only dinosaurs to survive the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous Period 65 million years ago. We do, however, have a handful of much older, non-avian dinosaurs at the museum.On the left above is a partial single tooth from Tyrannosaurus rex from the Late Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation in Montana, which was collected by Harley Garbani and donated to the museum by Harley and his wife Mary. The tooth was apparently found isolated, which is not uncommon with dinosaurs as they shed teeth throughout their lives. As is typical of Tyrannosaurus and other theropods, the tooth has serrated cutting edges, one of which is visible near the left edge of the tooth. There is noticeable apical wear at the tip of the tooth, which is somewhat rounded off.This tooth was one of the first subjects for our molding and casting program. At the center of the photo is an unpainted resin cast of the tooth, and on the right is a painted cast. The serrated cutting edge is actually more visible in the cast than in the original specimen.The original specimen is on display at the Western Science Center as part of the "Harley Garbani: Dinosaur Hunter" exhibit. Replicas of the tooth will be available in the museum store early next year.

The vast majority of the Western Science Center's fossil collection comes from Pleistocene deposits in Riverside County, so most of our specimens are less than 200,000 years old. Being so geologically young, birds are almost the only dinosaurs in our collection, as birds were the only dinosaurs to survive the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous Period 65 million years ago. We do, however, have a handful of much older, non-avian dinosaurs at the museum.On the left above is a partial single tooth from Tyrannosaurus rex from the Late Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation in Montana, which was collected by Harley Garbani and donated to the museum by Harley and his wife Mary. The tooth was apparently found isolated, which is not uncommon with dinosaurs as they shed teeth throughout their lives. As is typical of Tyrannosaurus and other theropods, the tooth has serrated cutting edges, one of which is visible near the left edge of the tooth. There is noticeable apical wear at the tip of the tooth, which is somewhat rounded off.This tooth was one of the first subjects for our molding and casting program. At the center of the photo is an unpainted resin cast of the tooth, and on the right is a painted cast. The serrated cutting edge is actually more visible in the cast than in the original specimen.The original specimen is on display at the Western Science Center as part of the "Harley Garbani: Dinosaur Hunter" exhibit. Replicas of the tooth will be available in the museum store early next year.

Harley Garbani exhibit opens at WSC

Last night more than 70 WSC members and supporters attended the sneak preview of our new permanent exhibit "Harley Garbani: Dinosaur Hunter".Harley Garbani grew up in the San Jacinto Valley, and it was during his childhood here that he developed his interest in paleontology and archaeology. He spent most of his life collecting fossils and artifacts in Southern California and in Garfield County, Montana. The Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation produced some of his most famous finds, including skulls of Tyrannosaurus and a juvenile Triceratops, casts of which are on display in our exhibit. His discoveries are housed in several museums, and he was the first recipient of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology's Morris F. Skinner Award for "...outstanding and sustained contributions to scientific knowledge through the making of important collections of fossil vertebrates."After several years of fundraising and design work, we held a reception last night that was attended by Harley's wife Mary and other members of the Garbani family, as well as by numerous WSC members and board members.

Last night more than 70 WSC members and supporters attended the sneak preview of our new permanent exhibit "Harley Garbani: Dinosaur Hunter".Harley Garbani grew up in the San Jacinto Valley, and it was during his childhood here that he developed his interest in paleontology and archaeology. He spent most of his life collecting fossils and artifacts in Southern California and in Garfield County, Montana. The Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation produced some of his most famous finds, including skulls of Tyrannosaurus and a juvenile Triceratops, casts of which are on display in our exhibit. His discoveries are housed in several museums, and he was the first recipient of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology's Morris F. Skinner Award for "...outstanding and sustained contributions to scientific knowledge through the making of important collections of fossil vertebrates."After several years of fundraising and design work, we held a reception last night that was attended by Harley's wife Mary and other members of the Garbani family, as well as by numerous WSC members and board members.

Starting today the Harley Garbani exhibit is open to everyone, and is included as part of the normal WSC admission.

Starting today the Harley Garbani exhibit is open to everyone, and is included as part of the normal WSC admission.