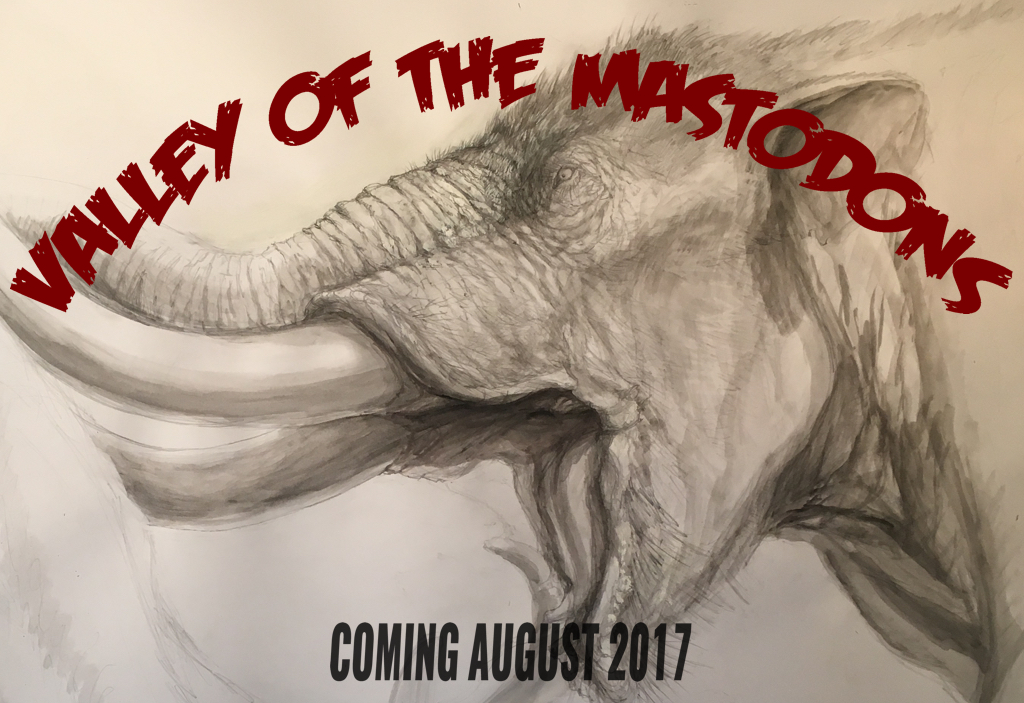

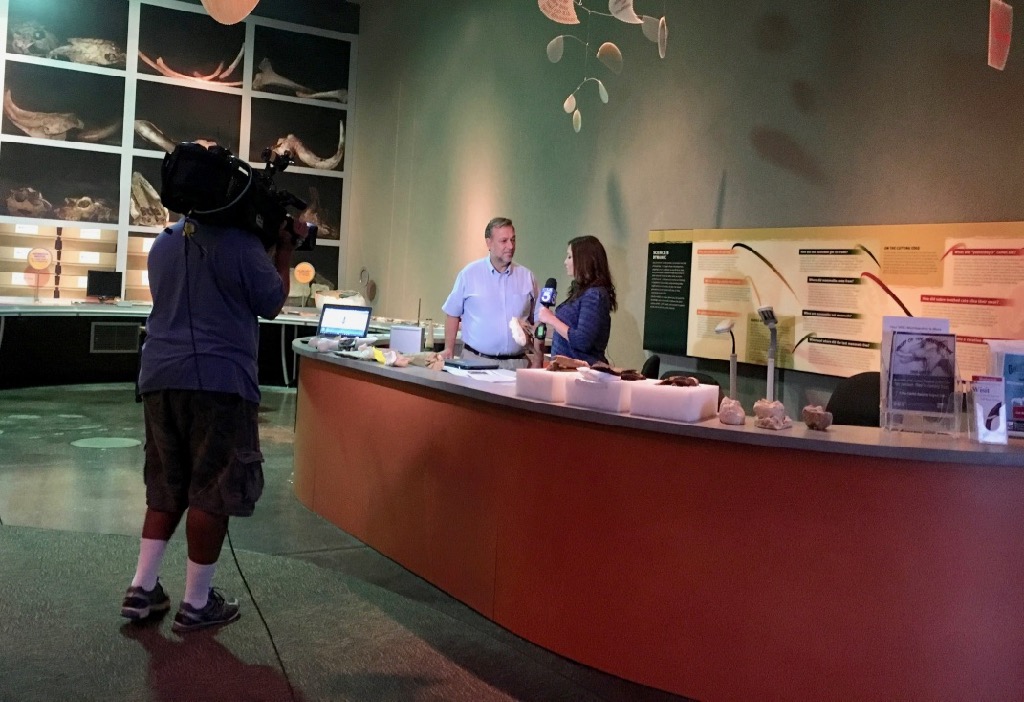

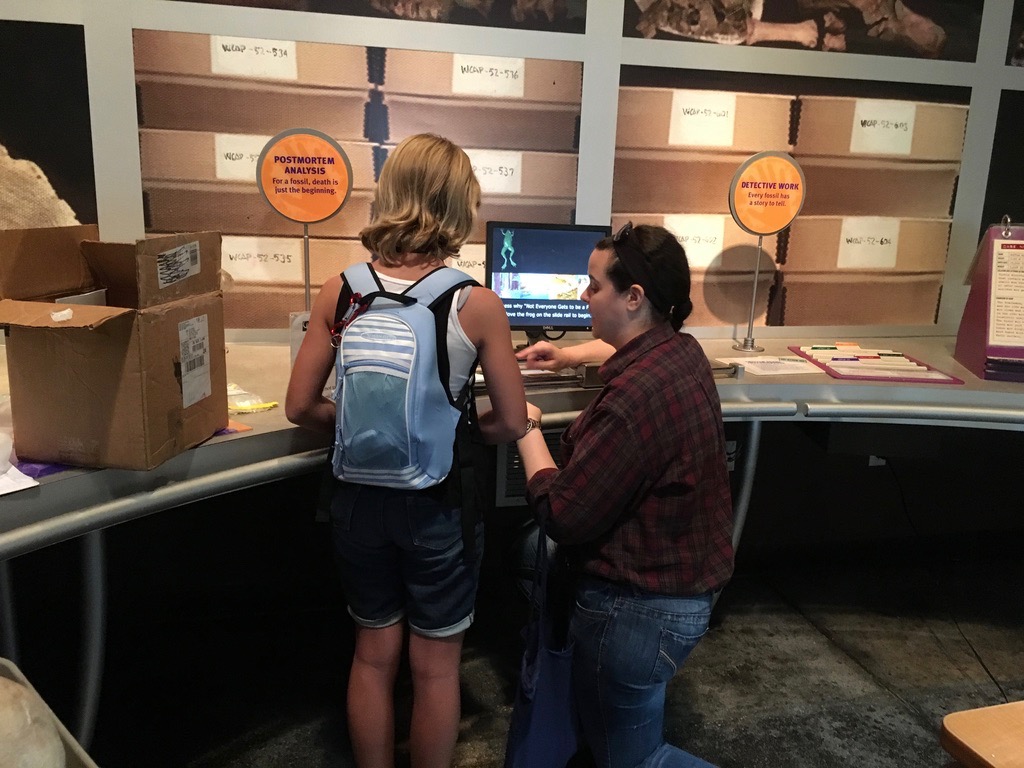

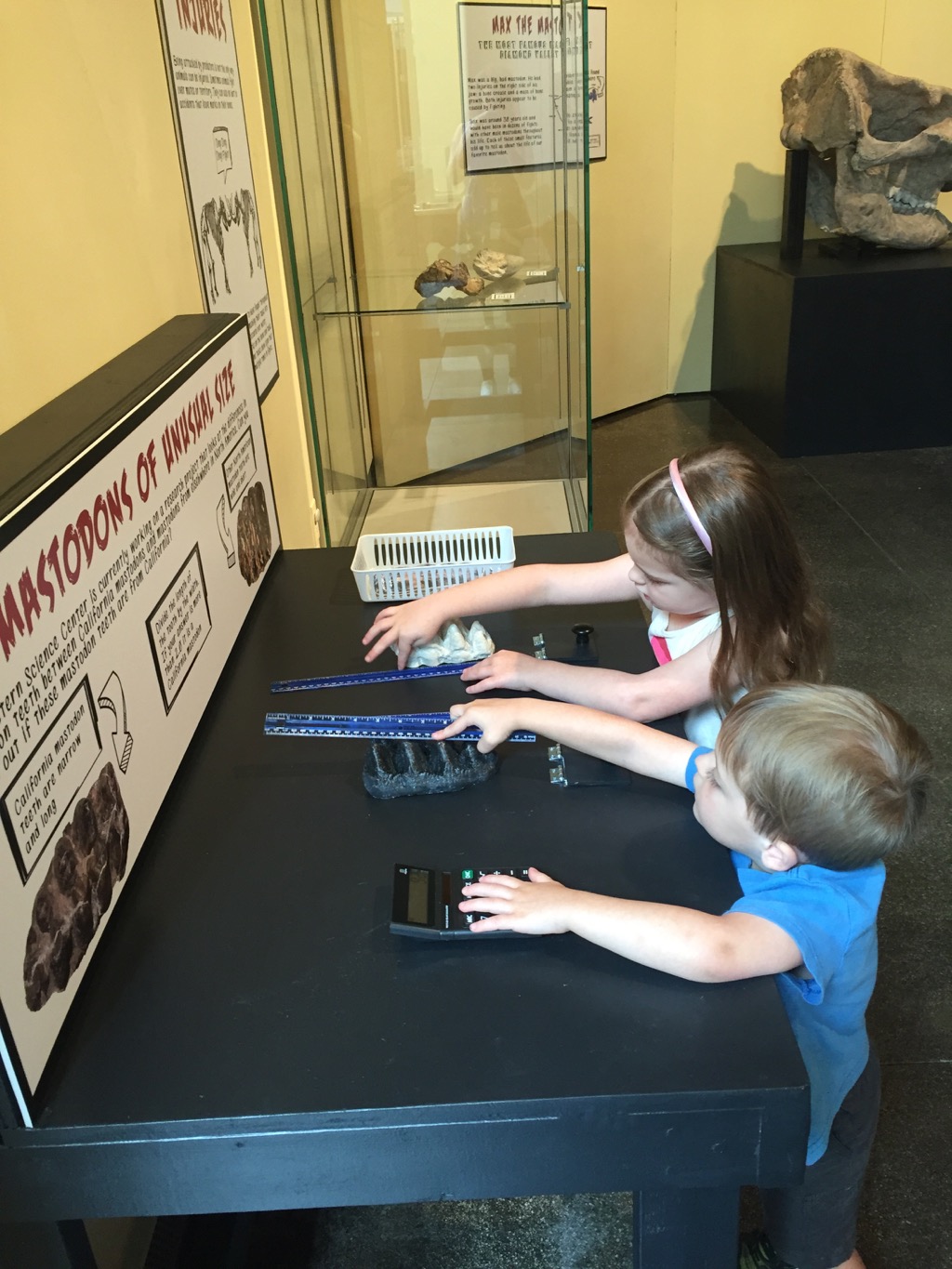

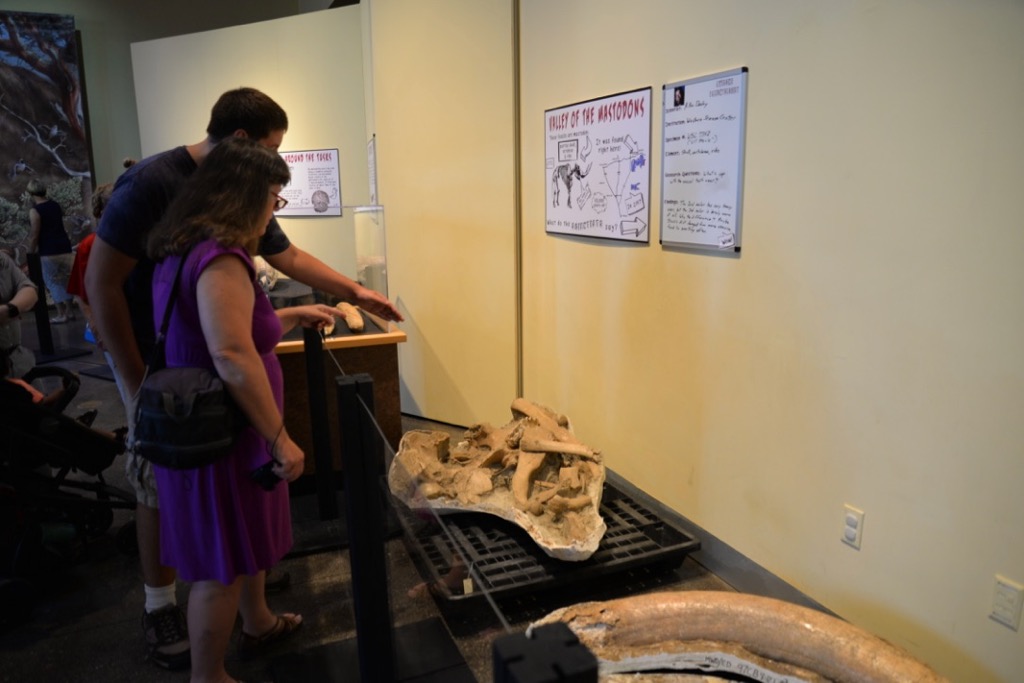

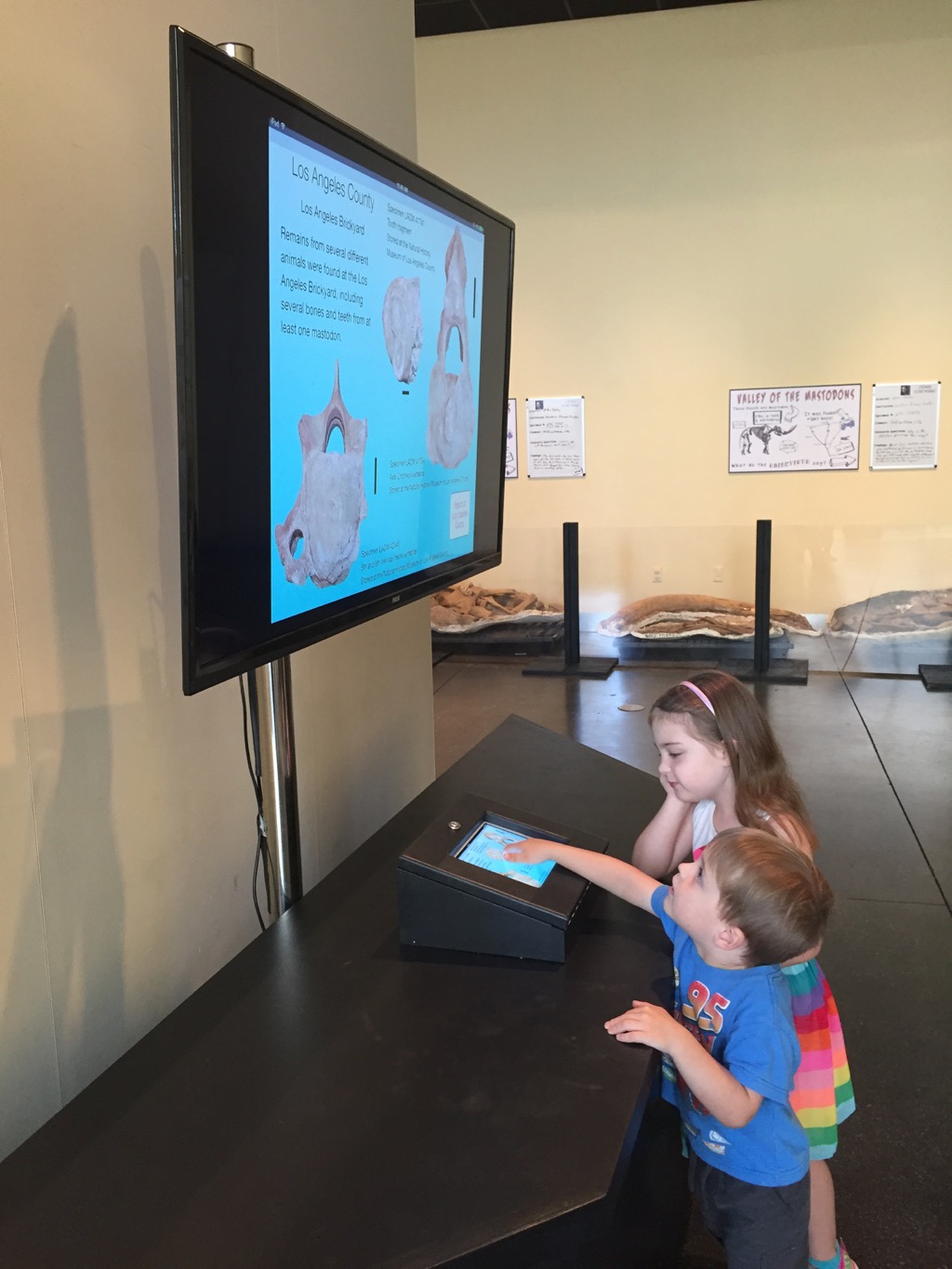

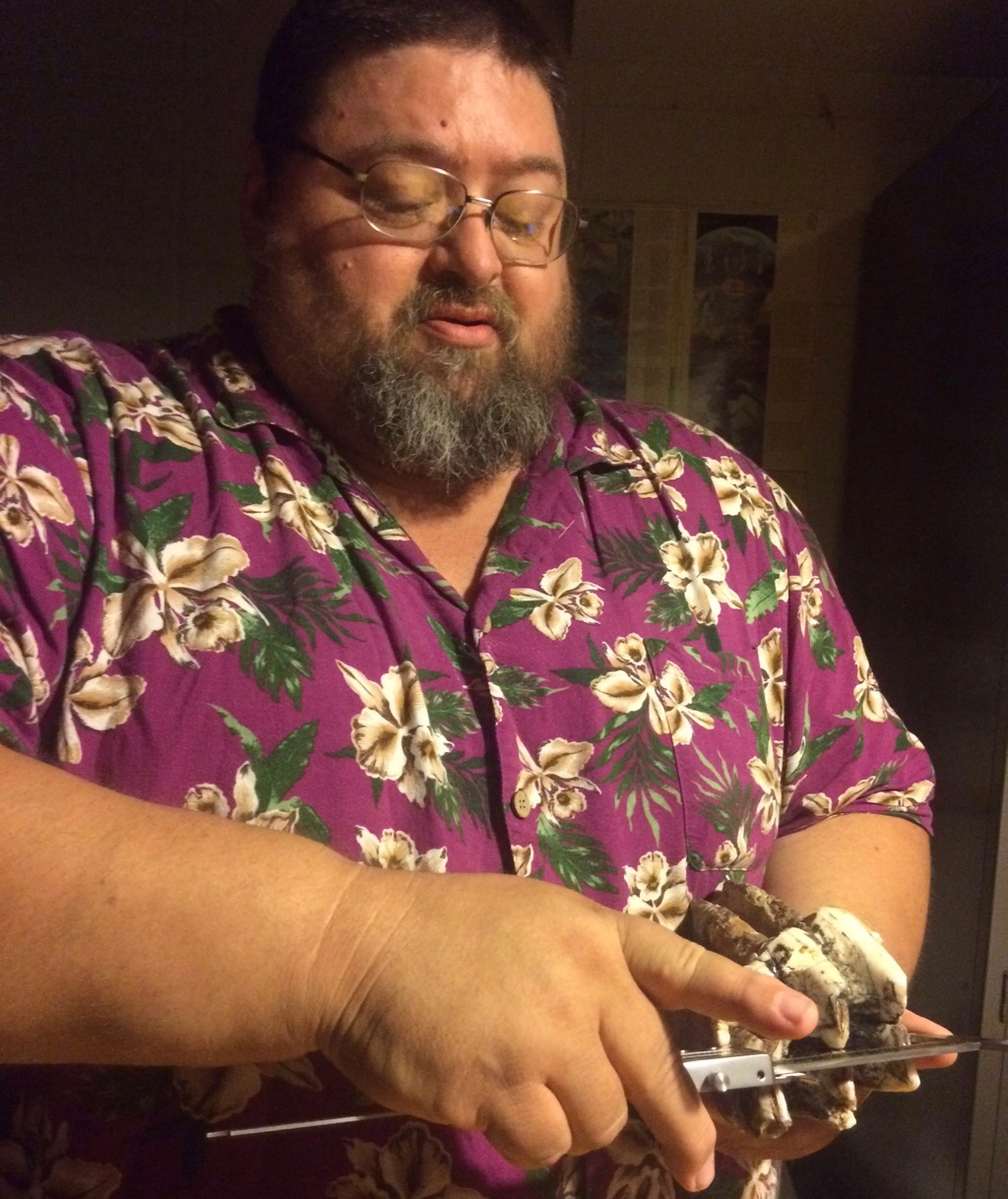

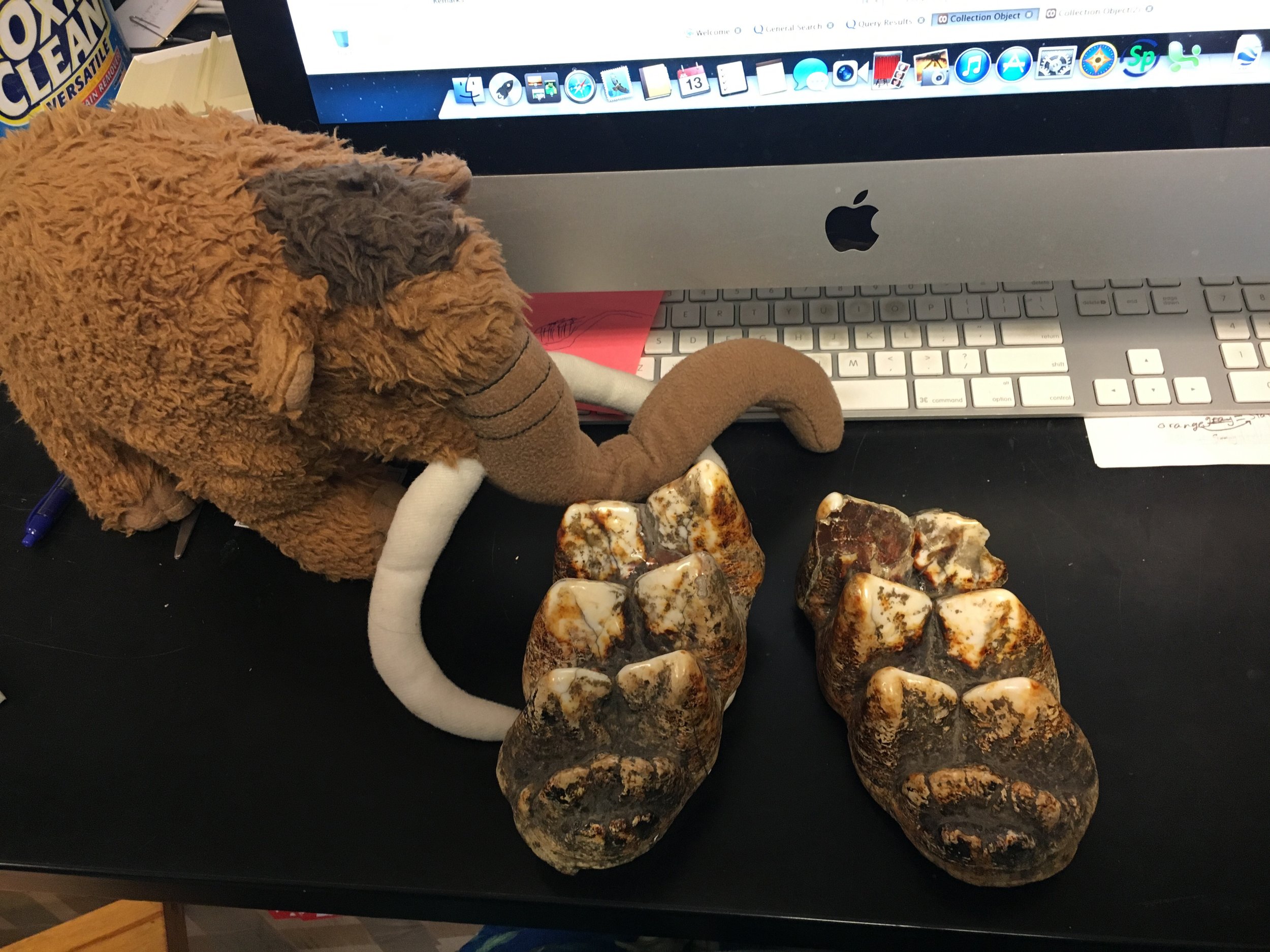

I missed doing a Fossil Friday post last week. But my reason was a good one: that was the opening day for our new exhibit, Valley of the Mastodons!Valley of the Mastodons was more than just an exhibit, however. It started with a 3-day symposium with 17 scientists and science communicators from the US and Canada examining the WSC mastodon collection, giving presentations, engaging with the public, and helping with the exhibit. Besides being what we believe to be the largest exhibit of mastodons in history, we're attempting to break new ground in making the act of research itself part of outreach, in real time.We had pretty good media exposure, with more to come:KTLA 5PLOS Paleo CommunityThe Press-EnterpriseSauropod Vertebra Picture of the WeekDontmesswithdinosaurs.comI'll have lots more to say about Valley of the Mastodons in the future, including at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Calgary later this month. But for now I want to thank our sponsors and supporters Golden Village Palms RV Resort, Abbott Vascular, Bone Clones, and Brian Engh Paleoart, as well as the participants that made this event such a success! Below are bunches of pictures from the event:

I missed doing a Fossil Friday post last week. But my reason was a good one: that was the opening day for our new exhibit, Valley of the Mastodons!Valley of the Mastodons was more than just an exhibit, however. It started with a 3-day symposium with 17 scientists and science communicators from the US and Canada examining the WSC mastodon collection, giving presentations, engaging with the public, and helping with the exhibit. Besides being what we believe to be the largest exhibit of mastodons in history, we're attempting to break new ground in making the act of research itself part of outreach, in real time.We had pretty good media exposure, with more to come:KTLA 5PLOS Paleo CommunityThe Press-EnterpriseSauropod Vertebra Picture of the WeekDontmesswithdinosaurs.comI'll have lots more to say about Valley of the Mastodons in the future, including at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Calgary later this month. But for now I want to thank our sponsors and supporters Golden Village Palms RV Resort, Abbott Vascular, Bone Clones, and Brian Engh Paleoart, as well as the participants that made this event such a success! Below are bunches of pictures from the event:

The role of museums

Inspired by Brian Switek’s recent article in Aeon, I was reminded of a post I wrote several years ago for “Updates from the Paleontology Lab” about different types of institutions that describe themselves with the term “museum”. What follows is an updated and edited version of that post.Over the course of my career I’ve had the opportunity to visit numerous natural history museums for a variety of reasons, as a researcher, a public lecturer, a tourist, and, of course, as an employee. The institutions are highly diverse in terms of their missions, and it’s instructive to reflect on those differences. The points I’m going to make are largely anecdotal, but should serve to give a general idea of the different types of natural history museums.During my time in Virginia, I made several visits to the Science Museum of Virginia (SMV), located in Richmond. SMV has a very large exhibit area and I was always impressed with the range and quality of hands-on interactives in their exhibits, but there were very few specimens on display.

Inspired by Brian Switek’s recent article in Aeon, I was reminded of a post I wrote several years ago for “Updates from the Paleontology Lab” about different types of institutions that describe themselves with the term “museum”. What follows is an updated and edited version of that post.Over the course of my career I’ve had the opportunity to visit numerous natural history museums for a variety of reasons, as a researcher, a public lecturer, a tourist, and, of course, as an employee. The institutions are highly diverse in terms of their missions, and it’s instructive to reflect on those differences. The points I’m going to make are largely anecdotal, but should serve to give a general idea of the different types of natural history museums.During my time in Virginia, I made several visits to the Science Museum of Virginia (SMV), located in Richmond. SMV has a very large exhibit area and I was always impressed with the range and quality of hands-on interactives in their exhibits, but there were very few specimens on display. Extinction exhibit at the Science Museum of Virginia.SMV is an excellent example of a science education center. These institutions generally have few (if any) collections, and usually what collections they have are used in education rather than research. They are generally staffed by educators, with few if any active research scientists. The primary audiences are families with school-age children or schools themselves, especially elementary and middle schools, and this is reflected in the types of exhibits that are selected. This is not to say that adults can’t benefit or enjoy these exhibits - just that they are not the primary audience.A number of colleges have campus museums; two that I’ve visited recently are the Joseph Moore Museum at Earlham College and the Museum of Earth Science at Radford University. While it used to be fairly common for small colleges to maintain museums, they fell into disfavor in recent decades; fortunately they may be experiencing a bit of a renaissance.

Extinction exhibit at the Science Museum of Virginia.SMV is an excellent example of a science education center. These institutions generally have few (if any) collections, and usually what collections they have are used in education rather than research. They are generally staffed by educators, with few if any active research scientists. The primary audiences are families with school-age children or schools themselves, especially elementary and middle schools, and this is reflected in the types of exhibits that are selected. This is not to say that adults can’t benefit or enjoy these exhibits - just that they are not the primary audience.A number of colleges have campus museums; two that I’ve visited recently are the Joseph Moore Museum at Earlham College and the Museum of Earth Science at Radford University. While it used to be fairly common for small colleges to maintain museums, they fell into disfavor in recent decades; fortunately they may be experiencing a bit of a renaissance. Allosaurus cast on display at the Joseph Moore Museum.Campus museums are almost as eclectic as the colleges that run them, but they do tend to have a few things in common. Collections at these museums are primarily for teaching (although there are exceptions; we’re including several Joseph Moore Museum specimens in the “Mastodons of Unusual Size” project). Most of these museum have few or no paid full-time staff, and often are run part-time by a faculty member. Most of the museums’ operational activities, including their programs, are conducted by students. Often these institutions serve as teaching museums, and are where many career museum professionals got their initial exposure to museum operations.

Allosaurus cast on display at the Joseph Moore Museum.Campus museums are almost as eclectic as the colleges that run them, but they do tend to have a few things in common. Collections at these museums are primarily for teaching (although there are exceptions; we’re including several Joseph Moore Museum specimens in the “Mastodons of Unusual Size” project). Most of these museum have few or no paid full-time staff, and often are run part-time by a faculty member. Most of the museums’ operational activities, including their programs, are conducted by students. Often these institutions serve as teaching museums, and are where many career museum professionals got their initial exposure to museum operations. Collecting mastodon data at the Joseph Moore Museum.Finally, there are research museums such as the Western Science Center. Many research museums are operated by federal, state, or local governments (I previously worked at the Virginia Museum of Natural History, a state-funded research museum). Some, such as the Florida Museum of Natural History, are departments within research universities, which are also often state government-supported. A few, such as the American Museum of Natural History and Western Science Center, are stand-alone non-profit institutions operated in most cases by private foundations. While research museums may have different origins and associations, they all share a common feature: a permanent collection of research specimens. The primary function of these museums is to preserve the specimens and associated data that form the basis of natural science. These museums will usually have a written collections policy that defines the scope of the collection, how specimens are acquired, and how they are made available for study. The collections supersede any particular staff member; the curators and collections staff are there primarily there to support and maintain the collections, not the other way around.

Collecting mastodon data at the Joseph Moore Museum.Finally, there are research museums such as the Western Science Center. Many research museums are operated by federal, state, or local governments (I previously worked at the Virginia Museum of Natural History, a state-funded research museum). Some, such as the Florida Museum of Natural History, are departments within research universities, which are also often state government-supported. A few, such as the American Museum of Natural History and Western Science Center, are stand-alone non-profit institutions operated in most cases by private foundations. While research museums may have different origins and associations, they all share a common feature: a permanent collection of research specimens. The primary function of these museums is to preserve the specimens and associated data that form the basis of natural science. These museums will usually have a written collections policy that defines the scope of the collection, how specimens are acquired, and how they are made available for study. The collections supersede any particular staff member; the curators and collections staff are there primarily there to support and maintain the collections, not the other way around.  Dr. Katy Smith working in the collections repository at the Western Science Center.Specimens in a research collection are selected for their scientific value. Many of these specimens may be visually appealing, but that’s not the reason they’re acquired. In fact, the majority of a research museum’s collections are rarely if ever viewed by anyone except specialists who incorporate the data from those specimens into their research. In this respect, research museums stand apart from science education centers and teaching museums.Of course, these are broad categories that tend to merge into one another. Many museums have a close relationship with colleges, even if they aren't actually operated by a college. Some science education centers have small but significant research collections (the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery is a science education center where we collected mastodon data). Nearly all museums put a lot of effort into public education, regardless of their primary focus. Nevertheless, I'd suggest that most natural history museums tend to fall closest to one of these three categories.With such a range of missions and holdings, why are all these disparate institutions called museums? There is one feature that they all tend to share: exhibits. Even though the primary function of a research museum is maintaining collections, exhibits are a critical supporting part of that mission. To extend an analogy that a friend once suggested to me, why does a football stadium or a theatre have seats? Why do we have art galleries? All the players, actors, or artists require is a field, stage, or easel. The seats in a stadium or theatre are for everyone else – those who aren’t athletes or actors. The theatre, art gallery, and playing field are venues for non-specialists to experience these activities. Likewise, museums are the stages that scientists use to present their work to others. The vast majority of scientific research is funded, in one way or another, by the public. We have an obligation to make the fruits of our scientific endeavors available to as many people as we can, and particularly to those who pay for them.With exhibits serving as one of the significant public faces of research, it’s easy for the public to become misled about the function of museums and exhibits, particularly when the term “museum” is used for a variety of institutions. It can seem to a visitor that the only reason museums exist is to have exhibits. In the case of a science education center such as SMV, this is actually the case; they are an institution that exists to provide science education, primarily through exhibits. But the knowledge that’s imparted in SMV’s exhibits came from somewhere; someone had to collect and interpret the raw data that led to those discoveries. That was done in university and government research facilities…and in research museums. Institutions such as WSC don’t just provide the scientific knowledge described in our own exhibits, but also for the exhibits in other venues that don’t perform research or maintain collections. For research museums, we don’t acquire collections in order to supply the exhibits; rather, the exhibits exist to teach the public about the significance of our collections. All these different types of museums may share exhibits as a common point, but they perform different, yet complimentary, roles in the advancement of science.

Dr. Katy Smith working in the collections repository at the Western Science Center.Specimens in a research collection are selected for their scientific value. Many of these specimens may be visually appealing, but that’s not the reason they’re acquired. In fact, the majority of a research museum’s collections are rarely if ever viewed by anyone except specialists who incorporate the data from those specimens into their research. In this respect, research museums stand apart from science education centers and teaching museums.Of course, these are broad categories that tend to merge into one another. Many museums have a close relationship with colleges, even if they aren't actually operated by a college. Some science education centers have small but significant research collections (the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery is a science education center where we collected mastodon data). Nearly all museums put a lot of effort into public education, regardless of their primary focus. Nevertheless, I'd suggest that most natural history museums tend to fall closest to one of these three categories.With such a range of missions and holdings, why are all these disparate institutions called museums? There is one feature that they all tend to share: exhibits. Even though the primary function of a research museum is maintaining collections, exhibits are a critical supporting part of that mission. To extend an analogy that a friend once suggested to me, why does a football stadium or a theatre have seats? Why do we have art galleries? All the players, actors, or artists require is a field, stage, or easel. The seats in a stadium or theatre are for everyone else – those who aren’t athletes or actors. The theatre, art gallery, and playing field are venues for non-specialists to experience these activities. Likewise, museums are the stages that scientists use to present their work to others. The vast majority of scientific research is funded, in one way or another, by the public. We have an obligation to make the fruits of our scientific endeavors available to as many people as we can, and particularly to those who pay for them.With exhibits serving as one of the significant public faces of research, it’s easy for the public to become misled about the function of museums and exhibits, particularly when the term “museum” is used for a variety of institutions. It can seem to a visitor that the only reason museums exist is to have exhibits. In the case of a science education center such as SMV, this is actually the case; they are an institution that exists to provide science education, primarily through exhibits. But the knowledge that’s imparted in SMV’s exhibits came from somewhere; someone had to collect and interpret the raw data that led to those discoveries. That was done in university and government research facilities…and in research museums. Institutions such as WSC don’t just provide the scientific knowledge described in our own exhibits, but also for the exhibits in other venues that don’t perform research or maintain collections. For research museums, we don’t acquire collections in order to supply the exhibits; rather, the exhibits exist to teach the public about the significance of our collections. All these different types of museums may share exhibits as a common point, but they perform different, yet complimentary, roles in the advancement of science.

Mastodons of Unusual Size - Denver Museum of Nature and Science

On Thursday Brett, Max, and I made our sixth stop on the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" tour, at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.The major reason for stopping in Denver was to examine specimens from the Snowmastodon Project. In 2010 during the construction of a reservoir at Snowmass Village several thousand Ice Age fossils were discovered. There were two especially remarkable features at the site. First, at an altitude of over 8,800 feet, it was one of the highest Ice Age deposits ever found. Second, by far the most common animals were mastodons, accounting for more than half of the bones recovered. From the Rocky Mountains west to the Pacific Ocean, the vast majority of known mastodons come from just three sites - Snowmass Village, Rancho La Brea, and Diamond Valkey Lake.There are a number of very well-preserved crania and mandibles from Snowmass in the Denver collection (Max is seen above with some of the mandibles), that range from very young, perhaps even fetal, animals to an individual that was so old that its last tooth was worn to the roots (we couldn't measure that one because there wasn't enough tooth left!):

On Thursday Brett, Max, and I made our sixth stop on the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" tour, at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.The major reason for stopping in Denver was to examine specimens from the Snowmastodon Project. In 2010 during the construction of a reservoir at Snowmass Village several thousand Ice Age fossils were discovered. There were two especially remarkable features at the site. First, at an altitude of over 8,800 feet, it was one of the highest Ice Age deposits ever found. Second, by far the most common animals were mastodons, accounting for more than half of the bones recovered. From the Rocky Mountains west to the Pacific Ocean, the vast majority of known mastodons come from just three sites - Snowmass Village, Rancho La Brea, and Diamond Valkey Lake.There are a number of very well-preserved crania and mandibles from Snowmass in the Denver collection (Max is seen above with some of the mandibles), that range from very young, perhaps even fetal, animals to an individual that was so old that its last tooth was worn to the roots (we couldn't measure that one because there wasn't enough tooth left!): With such a large mastodon sample, we were able to measure teeth from every position and a variety of different ages. This tiny maxilla fragment preserves the first two teeth, the second and third premolars:

With such a large mastodon sample, we were able to measure teeth from every position and a variety of different ages. This tiny maxilla fragment preserves the first two teeth, the second and third premolars: This maxilla has the third and fourth premolars:

This maxilla has the third and fourth premolars: And below is a maxilla fragment with the next three teeth, the first, second, and third molars all preserved:

And below is a maxilla fragment with the next three teeth, the first, second, and third molars all preserved:  Some of the Snowmass specimens are true giants. We measured one femur (actually the cast, below) that had a distal width 11% greater than Max's:

Some of the Snowmass specimens are true giants. We measured one femur (actually the cast, below) that had a distal width 11% greater than Max's: The Snowmass sample was an excellent addition to our dataset, but there were actually a few other mastodons in the DMNH collections. Below is apparently the only known mastodon tooth from Colorado that wasn't found at Snowmass:

The Snowmass sample was an excellent addition to our dataset, but there were actually a few other mastodons in the DMNH collections. Below is apparently the only known mastodon tooth from Colorado that wasn't found at Snowmass: There is also an Indiana mastodon in the Denver collections. This specimen has femora that are slightly larger than Max's, and relatively rare 5-lophid lower third molars:

There is also an Indiana mastodon in the Denver collections. This specimen has femora that are slightly larger than Max's, and relatively rare 5-lophid lower third molars:  We spent seven straight hours in the Denver collections, measuring 85 mastodon teeth. It's going to take awhile for me to sort through everything and see what we have, but a few initial impressions did jump out at me. Most significantly, the Snowmass mastodons don't seem to look much like the California mastodons. Almost none of the third molars have a length:width ratio of greater than 2 (I think only one specimen), while almost every California mastodon has a ratio greater than 2. More strikingly, it seems that every Snowmass mastodon had lower tusks (as seen below), a feature that has never been observed in a California mastodon.

We spent seven straight hours in the Denver collections, measuring 85 mastodon teeth. It's going to take awhile for me to sort through everything and see what we have, but a few initial impressions did jump out at me. Most significantly, the Snowmass mastodons don't seem to look much like the California mastodons. Almost none of the third molars have a length:width ratio of greater than 2 (I think only one specimen), while almost every California mastodon has a ratio greater than 2. More strikingly, it seems that every Snowmass mastodon had lower tusks (as seen below), a feature that has never been observed in a California mastodon. As I write this, Brett, Max, and I are on our way home to California. But this doesn't mark the end of "Mastodons of Unusual Size". We are still gathering data that's being supplied by other researchers, and still collecting data on California mastodons (we haven't even measured all the Diamond Valley Lake specimens yet). In October we'll be presenting our preliminary results at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Salt Lake City. And, of course, I'll be posing updates on our progress here, on Twitter, and at experiment.com.Thanks to all the curators and collections managers who provided access to the collections in their care, and to our experiment.com donors that made this trip possible.

As I write this, Brett, Max, and I are on our way home to California. But this doesn't mark the end of "Mastodons of Unusual Size". We are still gathering data that's being supplied by other researchers, and still collecting data on California mastodons (we haven't even measured all the Diamond Valley Lake specimens yet). In October we'll be presenting our preliminary results at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Salt Lake City. And, of course, I'll be posing updates on our progress here, on Twitter, and at experiment.com.Thanks to all the curators and collections managers who provided access to the collections in their care, and to our experiment.com donors that made this trip possible.

Mastodons of Unusual Size - University of Wyoming

Yesterday we made our fifth stop on the Mastodons of Unusual Size tour, the University of Wyoming Geological Museum in Laramie. Mastodons get increasingly scarce as you move west, but we had hopes that something would turn up in the excellent fossil mammal collections at the Geological Museum.With the help of Collections Manager Laura Vietti, we tracked down the only two teeth in the Geological Museum's collection, shown above with Max. Both of these teeth are lower third molars, but unfortunately the first lophid is missing on each tooth, so we weren't able to get measurements on either one. Even more surprising, it appears that both teeth are originally from Illinois. With these teeth ruled out, it appears that there are no known mastodon specimens from Wyoming!This is actually interesting news for us, because lots of Pleistocene animals from other species have been found in Wyoming over the years. If mastodons were common there, they should have been found by now, so it seems they were almost certainly absent or at least very rare in Wyoming. Interestingly, when I was planning this trip I contacted the South Dakota School of Mines Geological Museum in nearby Rapid City, which also holds lots of fossil mammals, only to be told that while their collections included lots of mammoths, they didn't have any mastodons at all. It seems that mastodons may have almost entirely avoided the high plains.Yesterday afternoon we left Laramie and headed to Denver for our next stop. More on that to come!

Yesterday we made our fifth stop on the Mastodons of Unusual Size tour, the University of Wyoming Geological Museum in Laramie. Mastodons get increasingly scarce as you move west, but we had hopes that something would turn up in the excellent fossil mammal collections at the Geological Museum.With the help of Collections Manager Laura Vietti, we tracked down the only two teeth in the Geological Museum's collection, shown above with Max. Both of these teeth are lower third molars, but unfortunately the first lophid is missing on each tooth, so we weren't able to get measurements on either one. Even more surprising, it appears that both teeth are originally from Illinois. With these teeth ruled out, it appears that there are no known mastodon specimens from Wyoming!This is actually interesting news for us, because lots of Pleistocene animals from other species have been found in Wyoming over the years. If mastodons were common there, they should have been found by now, so it seems they were almost certainly absent or at least very rare in Wyoming. Interestingly, when I was planning this trip I contacted the South Dakota School of Mines Geological Museum in nearby Rapid City, which also holds lots of fossil mammals, only to be told that while their collections included lots of mammoths, they didn't have any mastodons at all. It seems that mastodons may have almost entirely avoided the high plains.Yesterday afternoon we left Laramie and headed to Denver for our next stop. More on that to come!

Mastodons of Unusual Size - Joseph Moore Museum

This morning Brett, Max, and I visited the next museum on the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" tour, the Joseph Moore Museum at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana.The Joseph Moore Museum has a small but significant collection of Pleistocene fossils, with a mounted mastodon composite skeleton (above) as one of the centerpiece exhibits. Unfortunately, the teeth on this specimen are damaged and couldn't be measured, but there were several other mastodon teeth in the collection.

This morning Brett, Max, and I visited the next museum on the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" tour, the Joseph Moore Museum at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana.The Joseph Moore Museum has a small but significant collection of Pleistocene fossils, with a mounted mastodon composite skeleton (above) as one of the centerpiece exhibits. Unfortunately, the teeth on this specimen are damaged and couldn't be measured, but there were several other mastodon teeth in the collection. The tooth shown above, from Indiana, is a fairly typical lower third molar, with four lophids (the transverse enamel ridges) and a large posterior cingulid (the bumpy ridge at the back of the tooth that looks like a small lophid on the right in the image). Compare this to from another one in the Joseph Moore Museum collection below, from Ohio:

The tooth shown above, from Indiana, is a fairly typical lower third molar, with four lophids (the transverse enamel ridges) and a large posterior cingulid (the bumpy ridge at the back of the tooth that looks like a small lophid on the right in the image). Compare this to from another one in the Joseph Moore Museum collection below, from Ohio: This one is also a lower third molar, but this one has five lophids, and still has a posterior cingulid (posterior is on the left in this image). The five lophid morphology seems to show up in a small percentage of mastodons; we've seen it in only a few specimens so far on this trip, so it nice to find this one at Earlham.We were able to add five teeth to our dataset on this visit. Thanks to JMM Director Heather Lerner for providing access to Earlham's collection.

This one is also a lower third molar, but this one has five lophids, and still has a posterior cingulid (posterior is on the left in this image). The five lophid morphology seems to show up in a small percentage of mastodons; we've seen it in only a few specimens so far on this trip, so it nice to find this one at Earlham.We were able to add five teeth to our dataset on this visit. Thanks to JMM Director Heather Lerner for providing access to Earlham's collection.

Mastodons of Unusual Size - Boonshoft Museum of Discovery

Brett, Max, and I headed back into Ohio this morning for our next stop on the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" tour; the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery in Dayton.The most impressive Boonshoft mastodon is a more-or-less complete skull, shown above with Max. This was a young adult animal, perhaps 16-20 years old based on tooth wear. The first and second molars were erupted and functional, but the third molars had not yet erupted (the tooth eruption stage is very close to that of Xena, the Columbian mammoth on exhibit at WSC). This specimen also includes some postcranial bones, including both femora (below is the right one in anterior view):

Brett, Max, and I headed back into Ohio this morning for our next stop on the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" tour; the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery in Dayton.The most impressive Boonshoft mastodon is a more-or-less complete skull, shown above with Max. This was a young adult animal, perhaps 16-20 years old based on tooth wear. The first and second molars were erupted and functional, but the third molars had not yet erupted (the tooth eruption stage is very close to that of Xena, the Columbian mammoth on exhibit at WSC). This specimen also includes some postcranial bones, including both femora (below is the right one in anterior view): The presence of the femora is nice because they give us a data point for comparing tooth size to body size.Below is simultaneously the most intriguing and frustrating specimen we saw today:

The presence of the femora is nice because they give us a data point for comparing tooth size to body size.Below is simultaneously the most intriguing and frustrating specimen we saw today: This small lower third molar has both the size and proportions we would normally expect to see in a California mastodon. So, is this an Ohio specimen that looks like a Californian one? Maybe not! The Boonshoft has a few specimens acquired nearly 100 years ago from Rancho La Brea. This tooth has black residue on it that looks a lot like Rancho La Brea sediment. But...the specimen has no locality information, so we can't confirm where it's from (at least not without some expensive chemical testing)!We examined 17 teeth in the Boonshoft collection, which came from nine individuals; 4 of these teeth didn't have locality data and probably can't be included in our study. Most of the specimens are from Ohio, but we also examined a lower jaw from Florida. The addition of a skull with associated femora is significant, and prior to our Cincinnati and Boonshoft visits we had almost no Ohio or Kentucky specimens in our database. Thanks to Boonshoft's Anthropology Curator Bill Kennedy (below, with Max) for helping us with access to the collections.Tomorrow "Mastodons of Unusual Size" continues with our next stop.

This small lower third molar has both the size and proportions we would normally expect to see in a California mastodon. So, is this an Ohio specimen that looks like a Californian one? Maybe not! The Boonshoft has a few specimens acquired nearly 100 years ago from Rancho La Brea. This tooth has black residue on it that looks a lot like Rancho La Brea sediment. But...the specimen has no locality information, so we can't confirm where it's from (at least not without some expensive chemical testing)!We examined 17 teeth in the Boonshoft collection, which came from nine individuals; 4 of these teeth didn't have locality data and probably can't be included in our study. Most of the specimens are from Ohio, but we also examined a lower jaw from Florida. The addition of a skull with associated femora is significant, and prior to our Cincinnati and Boonshoft visits we had almost no Ohio or Kentucky specimens in our database. Thanks to Boonshoft's Anthropology Curator Bill Kennedy (below, with Max) for helping us with access to the collections.Tomorrow "Mastodons of Unusual Size" continues with our next stop.

Mastodons of Unusual Size - Cincinnati Museum of Natural History

After leaving Baton Rouge, Brett and I (accompanied by Max the Mastodon) headed north to our second data collection stop: the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History. The Overmyer mastodon from Indiana is one of the premier CMNH mastodons (Max is shown above with the lower jaw). This specimen has actually been published, so much of the data we needed was already available, but we were able to get measurements on postcranial bones and photos of the lower teeth.All told, we took measurements on 2 femora and 19 teeth, although 6 of the teeth have limited locality information. Several of the teeth were quite large, although none were as big as the monster tooth from Baton Rouge we saw on Tuesday. The lower jaw below was particularly interesting:

After leaving Baton Rouge, Brett and I (accompanied by Max the Mastodon) headed north to our second data collection stop: the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History. The Overmyer mastodon from Indiana is one of the premier CMNH mastodons (Max is shown above with the lower jaw). This specimen has actually been published, so much of the data we needed was already available, but we were able to get measurements on postcranial bones and photos of the lower teeth.All told, we took measurements on 2 femora and 19 teeth, although 6 of the teeth have limited locality information. Several of the teeth were quite large, although none were as big as the monster tooth from Baton Rouge we saw on Tuesday. The lower jaw below was particularly interesting: This specimen only has third molars, which are heavily worn across their entire length; the second molars have fallen out and the sockets have grown over. This was a really old animal when it died, very likely past 60 years old.The lower third molar below, from Kentucky, is also noteworthy for a couple of reasons:

This specimen only has third molars, which are heavily worn across their entire length; the second molars have fallen out and the sockets have grown over. This was a really old animal when it died, very likely past 60 years old.The lower third molar below, from Kentucky, is also noteworthy for a couple of reasons: First, it has five distinct lophs on the crown, instead of the four we usually see in Mammut third molars. Second, this is a remarkably narrow tooth; it's actually even narrow by California standards. So far we've only seen a handful of teeth with these proportions outside of California. That said, this is still a large tooth, much longer than any California tooth.After leaving Cincinnati we headed north to Richmond, Indiana, where we'll spend the next few days while visiting several area museums.

First, it has five distinct lophs on the crown, instead of the four we usually see in Mammut third molars. Second, this is a remarkably narrow tooth; it's actually even narrow by California standards. So far we've only seen a handful of teeth with these proportions outside of California. That said, this is still a large tooth, much longer than any California tooth.After leaving Cincinnati we headed north to Richmond, Indiana, where we'll spend the next few days while visiting several area museums.

Mastodons of Unusual Size - LSU

Today Brett and I made our first stop on our experiment.com - funded trip to collect data on mastodon tooth proportions: Louisiana State University.I received my Ph.D. from LSU in 1998, and this was only the second time I've been on campus since graduating. My graduate advisor, Dr. Judith Schiebout, is still at LSU, and Dr. Ting Suyin, who was a graduate student the same time I was there, is now LSU's vertebrate fossil collections manager:

Today Brett and I made our first stop on our experiment.com - funded trip to collect data on mastodon tooth proportions: Louisiana State University.I received my Ph.D. from LSU in 1998, and this was only the second time I've been on campus since graduating. My graduate advisor, Dr. Judith Schiebout, is still at LSU, and Dr. Ting Suyin, who was a graduate student the same time I was there, is now LSU's vertebrate fossil collections manager: Of course, our real reason for being here was to measure mastodons. We collected measurements and photographs for 17 teeth, although only 13 are suitable for the database (the others are too poorly preserved for a complete set of measurements).While the tooth proportions of the Louisiana specimens were about what we would expect for teeth from the Gulf Coast (relatively much wider than California specimens), I was struck by how large some of these teeth are. The tooth at the top, an upper 3rd molar from the Tunica Hills region, is a pretty large tooth that is both longer and wider than any California tooth. But even it was dwarfed by this monster from Baton Rouge:

Of course, our real reason for being here was to measure mastodons. We collected measurements and photographs for 17 teeth, although only 13 are suitable for the database (the others are too poorly preserved for a complete set of measurements).While the tooth proportions of the Louisiana specimens were about what we would expect for teeth from the Gulf Coast (relatively much wider than California specimens), I was struck by how large some of these teeth are. The tooth at the top, an upper 3rd molar from the Tunica Hills region, is a pretty large tooth that is both longer and wider than any California tooth. But even it was dwarfed by this monster from Baton Rouge:

These are occlusal views of the upper right 2nd molar and lower right 3rd molar; the 3rd molar is damaged, so we don't have the full width. These teeth are absolutely enormous. The 3rd molar is the second longest tooth in our database, and is more than 2.5 cm longer than any California m3. The M2 is 117.7 mm wide, the only M2 in our data set that's more than 100 mm wide!Below, Brett is holding a maxilla fragment with an M3 from another Louisiana specimen we measured today:

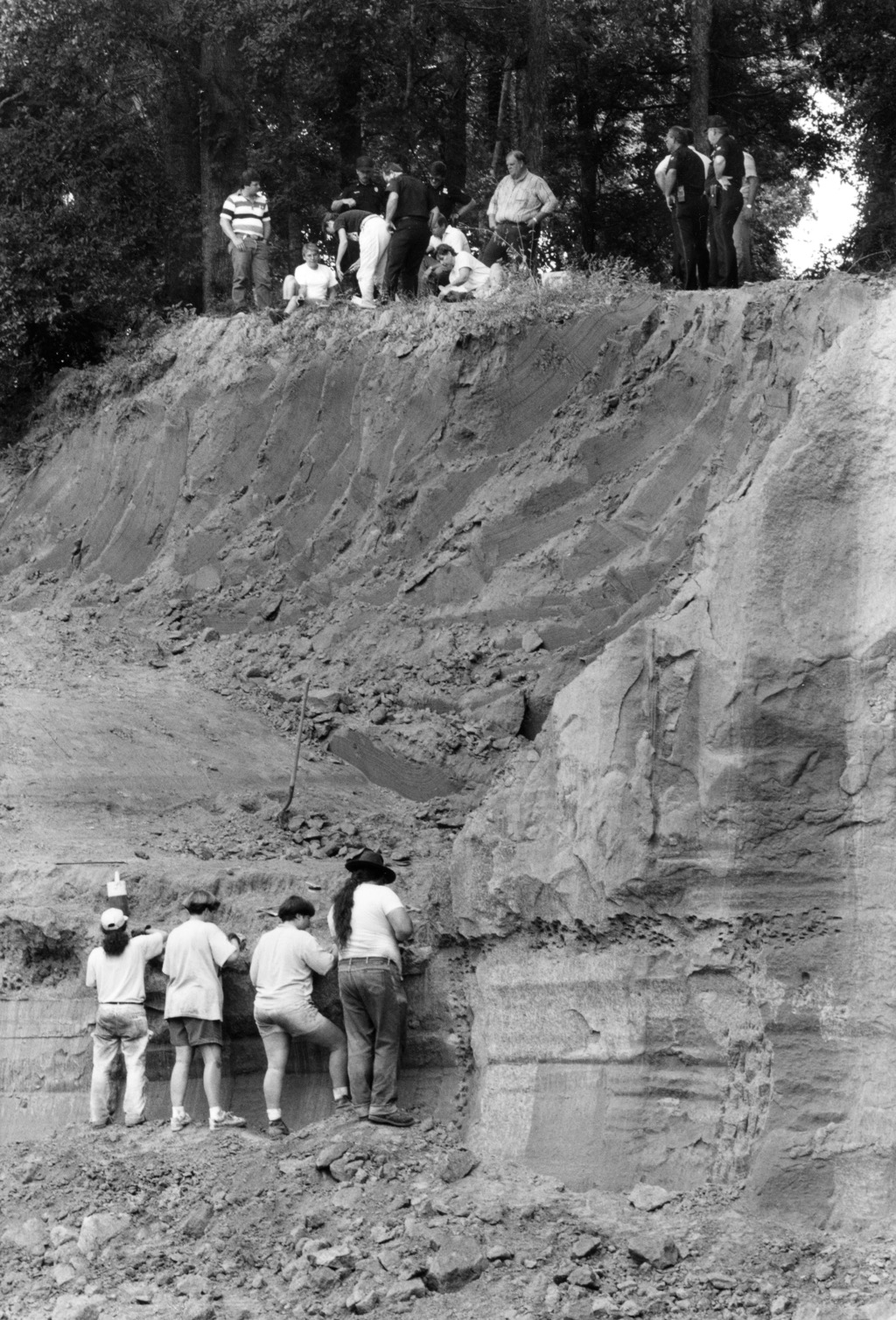

These are occlusal views of the upper right 2nd molar and lower right 3rd molar; the 3rd molar is damaged, so we don't have the full width. These teeth are absolutely enormous. The 3rd molar is the second longest tooth in our database, and is more than 2.5 cm longer than any California m3. The M2 is 117.7 mm wide, the only M2 in our data set that's more than 100 mm wide!Below, Brett is holding a maxilla fragment with an M3 from another Louisiana specimen we measured today: This specimen is special to me, because Brett and I led the excavation that recovered it. Brett and I were married in 1994, and after our honeymoon we drove to Baton Rouge where I was enrolled as a graduate student and Brett was starting a job as a lab technician for Dr. Schiebout. Immediately after we arrived we were called out to Angola, Louisiana to examine possible fossils that had been uncovered during a construction project at the Louisiana State Penitentiary. The remains turned out to be this specimen, and over the next several weeks Brett and I led an LSU crew on an excavation at the prison (this remains the only mastodon I've ever personally excavated, and the only time I've run an excavation inside a prison!). At the time we received a good deal of local media coverage, which only intensified when during the course of the excavation we discovered an unmarked and eroding 1800's-era cemetery directly above the excavation site. The photos below originally ran in the Baton Rouge Advocate, showing archaeologists working on the cemetery site at the top of the hill while we paleontologists simultaneously worked on the mastodon below them, and a closeup of the archaeological site:

This specimen is special to me, because Brett and I led the excavation that recovered it. Brett and I were married in 1994, and after our honeymoon we drove to Baton Rouge where I was enrolled as a graduate student and Brett was starting a job as a lab technician for Dr. Schiebout. Immediately after we arrived we were called out to Angola, Louisiana to examine possible fossils that had been uncovered during a construction project at the Louisiana State Penitentiary. The remains turned out to be this specimen, and over the next several weeks Brett and I led an LSU crew on an excavation at the prison (this remains the only mastodon I've ever personally excavated, and the only time I've run an excavation inside a prison!). At the time we received a good deal of local media coverage, which only intensified when during the course of the excavation we discovered an unmarked and eroding 1800's-era cemetery directly above the excavation site. The photos below originally ran in the Baton Rouge Advocate, showing archaeologists working on the cemetery site at the top of the hill while we paleontologists simultaneously worked on the mastodon below them, and a closeup of the archaeological site:

(That really is Brett and me, 22 years ago!)After documentation, the human remains were reburied in a new location. The mastodon remained in jackets until after I graduated, and was finally prepared sometime after 2000. Today was the first time Brett and I had seen the specimen since excavating it in 1994!Tomorrow we leave Baton Rouge and head north to visit more museums. Follow along here and on Max's Twitter feed (@MaxMastodon) and at #MastodonsOfUnusualSize.

(That really is Brett and me, 22 years ago!)After documentation, the human remains were reburied in a new location. The mastodon remained in jackets until after I graduated, and was finally prepared sometime after 2000. Today was the first time Brett and I had seen the specimen since excavating it in 1994!Tomorrow we leave Baton Rouge and head north to visit more museums. Follow along here and on Max's Twitter feed (@MaxMastodon) and at #MastodonsOfUnusualSize.

Fossil Friday - Stories from Bones exhibit

For Fossil Friday this week, I want to highlight Western Science Center's new exhibit "Stories from Bones", which opens tomorrow.While WSC has excellent paleontology exhibits, as with any museum with a large collection many of the specimens are not on public display. There are a variety of reasons for this. Of course, the biggest obstacle is money; cases, information panels, interactive, floor space, and other requirements for an effective display are all expensive, and even the healthiest museums operate on a shoestring budget. Besides money issues, many specimens are just not suitable for display. Perhaps they're too fragile to risk moving around too much, or too fragmentary to interpret for the public (a specimen that visually looks like a piece of junk can still produce valuable scientific data). Even with all these limitations, we strive to make as much of our collections accessible to the public as possible. "Stories from Bones" is a result of that effort.

For Fossil Friday this week, I want to highlight Western Science Center's new exhibit "Stories from Bones", which opens tomorrow.While WSC has excellent paleontology exhibits, as with any museum with a large collection many of the specimens are not on public display. There are a variety of reasons for this. Of course, the biggest obstacle is money; cases, information panels, interactive, floor space, and other requirements for an effective display are all expensive, and even the healthiest museums operate on a shoestring budget. Besides money issues, many specimens are just not suitable for display. Perhaps they're too fragile to risk moving around too much, or too fragmentary to interpret for the public (a specimen that visually looks like a piece of junk can still produce valuable scientific data). Even with all these limitations, we strive to make as much of our collections accessible to the public as possible. "Stories from Bones" is a result of that effort.

Mammoth jaw display in "Stories from Bones".

Mammoth jaw display in "Stories from Bones".

An important aspect of planning an effective exhibit is developing a theme. An exhibit is telling a story, and you need to be aware of what that story is as the exhibit is being designed. The theme might be "We have a bunch of stuff!", but while that was a common theme in museums a century ago (and one I personally appreciate), it does not generally make for the most informative exhibit experience for the majority of visitors.Once the theme is established, it's important to stick to it, so that the exhibit story remains coherent. Imagine reading a mystery novel in which three chapters are devoted to a history of the development of the gunpowder used in the crime, and an additional chapter describes the etymology of the last name of the victim, when neither is important to the outcome of the story. Each of these things might be individually interesting, but if you try to talk about all of them then you risk obscuring everything. There is a real risk of this "mission creep" in an exhibit based on a data-rich field such as paleontology. We might talk about evolutionary relationships, paleoenvironmental indicators, biogeographic information, site-specific descriptions, or an array of other things. Talking about any of these might be a good idea; talking about all of them is a bad idea.The permanent paleontology exhibit at WSC does this very well. The exhibit is basically a review of the Diamond Valley Lake Local Fauna; what was here, how does it compare to the rest of Southern California, and (as a secondary point) what does it tell us about the local Pleistocene paleoenvironment. In contrast, "Stories from Bones" asks "What do these fossils tell us about the lives and deaths of these individual animals?".To that end, "Stories" has a series of displays that talk about how paleontologists determine how old an animal was when it died. We have several cases that look at tooth replacement in proboscideans, horses, and bison, such as the two mammoth jaws above (they're close to the same size, but one animal was about 30 years older than the other), or the three bison dentaries shown below that represent young, middle-aged, and elderly animals.

Bison jaw display in "Stories from Bones".

Bison jaw display in "Stories from Bones".

We have several examples of bones that were broken and healed, evidence of events that took place during an animal's life:

Broken and healed bones in "Stories from Bones".

Broken and healed bones in "Stories from Bones".

We also have several cases that describe taphonomic features, looking at what happened to an animal at or immediately after death.We designed and built a number of interactive displays for this exhibit. The most prominent is a cast and video of the CT scans of Max the Mastodon's lower jaw, taken back in August.

Max's CT-scan station in "Stories from Bones" during installation, under the watchful eye of @MaxMastodon.

Max's CT-scan station in "Stories from Bones" during installation, under the watchful eye of @MaxMastodon.

We're proud of the fact that several of our interactive displays ask visitors to map or measure specimens and reach conclusions based on their data:

A more extensive version of the bison tooth display shown here is also available as a guided activity for school groups visiting the museum, and as a kit available for purchase.If you're a regular reader of this blog, you'll find that "Stories from Bones" draws heavily from my past "Fossil Friday" posts. For most of those specimens, this is the first time they've ever been on public display, so if you're near Southern California make sure to stop by the museum. "Stories from Bones" opens on October 31, and will remain open into May 2016.

A more extensive version of the bison tooth display shown here is also available as a guided activity for school groups visiting the museum, and as a kit available for purchase.If you're a regular reader of this blog, you'll find that "Stories from Bones" draws heavily from my past "Fossil Friday" posts. For most of those specimens, this is the first time they've ever been on public display, so if you're near Southern California make sure to stop by the museum. "Stories from Bones" opens on October 31, and will remain open into May 2016.

Fossil Friday - Alamosaurus neck vertebrae

This week I've been attending the annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP) meeting, which is being held this year in Dallas. SVP usually is held in a city with a natural history museum, and on Wednesday night the local museum will generally host a welcome reception. So for this week's Fossil Friday I photographed one of the highlights of the Perot Museum of Nature and Science's exhibits, the neck of Alamosaurus.Alamosaurus was a large sauropod dinosaur that has been found in Cretaceous sediments in the southwestern United States; this specimen is from Big Bend National Park in Texas. While not as famous as its older Jurassic relatives like Brontosaurus, Alamosaurus was just as large and impressive. This is easy to see when you realize that in the photo above you can only see 8 neck vertebrae!This image is taken as if you're standing near the base of the neck on the right side, looking forward, so the head would be toward the far right. There were at least a few more vertebrae at the base of the skull that were not preserved in this specimen, and more at the base of the neck as well. In fact, there is a ninth vertebra on exhibit, but the neck is so large that with the reception crowds I couldn't get far enough away to get all nine vertebrae in one photo from this angle. So here are all nine, looking from the front to the back:

This week I've been attending the annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology (SVP) meeting, which is being held this year in Dallas. SVP usually is held in a city with a natural history museum, and on Wednesday night the local museum will generally host a welcome reception. So for this week's Fossil Friday I photographed one of the highlights of the Perot Museum of Nature and Science's exhibits, the neck of Alamosaurus.Alamosaurus was a large sauropod dinosaur that has been found in Cretaceous sediments in the southwestern United States; this specimen is from Big Bend National Park in Texas. While not as famous as its older Jurassic relatives like Brontosaurus, Alamosaurus was just as large and impressive. This is easy to see when you realize that in the photo above you can only see 8 neck vertebrae!This image is taken as if you're standing near the base of the neck on the right side, looking forward, so the head would be toward the far right. There were at least a few more vertebrae at the base of the skull that were not preserved in this specimen, and more at the base of the neck as well. In fact, there is a ninth vertebra on exhibit, but the neck is so large that with the reception crowds I couldn't get far enough away to get all nine vertebrae in one photo from this angle. So here are all nine, looking from the front to the back:  The Perot Museum asked Research Casting International to produce a cast reconstruction of Alamosaurus based on these vertebrae and other Alamosaurus specimens. The cast is also on exhibit:

The Perot Museum asked Research Casting International to produce a cast reconstruction of Alamosaurus based on these vertebrae and other Alamosaurus specimens. The cast is also on exhibit: The people standing around the exhibit give an idea of scale. If that's not enough, that little theropod dinosaur standing beside Alamosaurus is Tyrannosaurus, and a Columbian mammoth is just visible at the lower left. By any standards, Alamosaurus was a huge animal!For more abut Alamosaurus, and to see photos of this specimen in the field, visit the SV-POW! blog.

The people standing around the exhibit give an idea of scale. If that's not enough, that little theropod dinosaur standing beside Alamosaurus is Tyrannosaurus, and a Columbian mammoth is just visible at the lower left. By any standards, Alamosaurus was a huge animal!For more abut Alamosaurus, and to see photos of this specimen in the field, visit the SV-POW! blog.

Visiting the Raymond M. Alf Museum

I spent today continuing to familiarize myself with Southern California by visiting the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology, located in Claremont on the campus of The Webb Schools. Once I arrived, Museum Director Don Lofgren, Curator Andy Farke, and Outreach Director Kathy Sanders kindly spent the better part of a day showing me around their museum and discussing museum operations and California paleontology.The Raymond Alf Museum is operated by The Webb Schools, a private high school, and paleontology and museum operations are heavily integrated into the school's curriculum. Many students participate as authors on research projects, including the description of "Joe", a baby Parasaurolophus published last year in PeerJ, and now on exhibit in the museum:

I spent today continuing to familiarize myself with Southern California by visiting the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology, located in Claremont on the campus of The Webb Schools. Once I arrived, Museum Director Don Lofgren, Curator Andy Farke, and Outreach Director Kathy Sanders kindly spent the better part of a day showing me around their museum and discussing museum operations and California paleontology.The Raymond Alf Museum is operated by The Webb Schools, a private high school, and paleontology and museum operations are heavily integrated into the school's curriculum. Many students participate as authors on research projects, including the description of "Joe", a baby Parasaurolophus published last year in PeerJ, and now on exhibit in the museum:

Of course, the Western Science Center also shares a campus with a school, the Western Center Academy. One of my goals in visiting the Alf Museum is to see how they've combined their research and educational efforts.Besides "Joe" there are tons of interesting fossils and casts on display in the museum. There are numerous titanothere skulls from Eocene deposits in South Dakota and Nebraska:

Of course, the Western Science Center also shares a campus with a school, the Western Center Academy. One of my goals in visiting the Alf Museum is to see how they've combined their research and educational efforts.Besides "Joe" there are tons of interesting fossils and casts on display in the museum. There are numerous titanothere skulls from Eocene deposits in South Dakota and Nebraska:

The Alf has one of the most impressive displays of fossil vertebrate trackways I've ever seen. There are plenty of dinosaur tracks, but how many museums have multiple examples of fossil camel tracks?

The Alf has one of the most impressive displays of fossil vertebrate trackways I've ever seen. There are plenty of dinosaur tracks, but how many museums have multiple examples of fossil camel tracks?

There are also numerous impressive slabs of Permian Coconino Sandstone that are covered with multiple reptile trackways:

There are also numerous impressive slabs of Permian Coconino Sandstone that are covered with multiple reptile trackways:

I'd like to thank Don, Andy, Kathy, and the rest of the staff at the Raymond Alf Museum for taking the time to meet and show me around their excellent museum.

I'd like to thank Don, Andy, Kathy, and the rest of the staff at the Raymond Alf Museum for taking the time to meet and show me around their excellent museum.

Visiting the Cooper Center

Last Thursday I had my first opportunity to visit The Cooper Center, Orange County's primary repository for paleontological and archaeological remains (WSC performs a similar role for Riverside County). The Cooper Center recently hosted the Prehistoric OC festival, but things had settled down enough for paleontology curator Meredith Riven to show me around the collections.The Cooper Center's collections are vast, and are the result of many decades of collection by many different professional and amateur paleontologists as well as by various mitigation companies. As might be expected with such a large collection amassed over many years by different sources, much of the material is in need of cataloging, preparation, and rehousing. Fortunately, the National Science Foundation has a program to address such issues, and the Cooper Center recently received a collections improvement grant to help with this monumental task.

Last Thursday I had my first opportunity to visit The Cooper Center, Orange County's primary repository for paleontological and archaeological remains (WSC performs a similar role for Riverside County). The Cooper Center recently hosted the Prehistoric OC festival, but things had settled down enough for paleontology curator Meredith Riven to show me around the collections.The Cooper Center's collections are vast, and are the result of many decades of collection by many different professional and amateur paleontologists as well as by various mitigation companies. As might be expected with such a large collection amassed over many years by different sources, much of the material is in need of cataloging, preparation, and rehousing. Fortunately, the National Science Foundation has a program to address such issues, and the Cooper Center recently received a collections improvement grant to help with this monumental task.

Note the earthquake restraints, something I didn't have to bother with in Virginia!A lot of the Cooper Center specimens represent marine animals, including this huge partial whale skeleton:

Note the earthquake restraints, something I didn't have to bother with in Virginia!A lot of the Cooper Center specimens represent marine animals, including this huge partial whale skeleton:

A tiny, rather enigmatic skull of a baleen whale:

A tiny, rather enigmatic skull of a baleen whale:

Meredith and I also spent part of the day at California State, Fullerton to meet with Jim Parham and Gabe Santos. Many of the CS Fullerton paleontology students work on Cooper Center specimens, and there's currently an impressive exhibit at the campus library about Orange County fossils and student research on them:

Meredith and I also spent part of the day at California State, Fullerton to meet with Jim Parham and Gabe Santos. Many of the CS Fullerton paleontology students work on Cooper Center specimens, and there's currently an impressive exhibit at the campus library about Orange County fossils and student research on them:

Thanks to Meredith, Jim, and Gabe for spending the day teaching me about Orange County fossils (and also to Jim for providing dark glass so I could see the solar eclipse)!

Thanks to Meredith, Jim, and Gabe for spending the day teaching me about Orange County fossils (and also to Jim for providing dark glass so I could see the solar eclipse)!