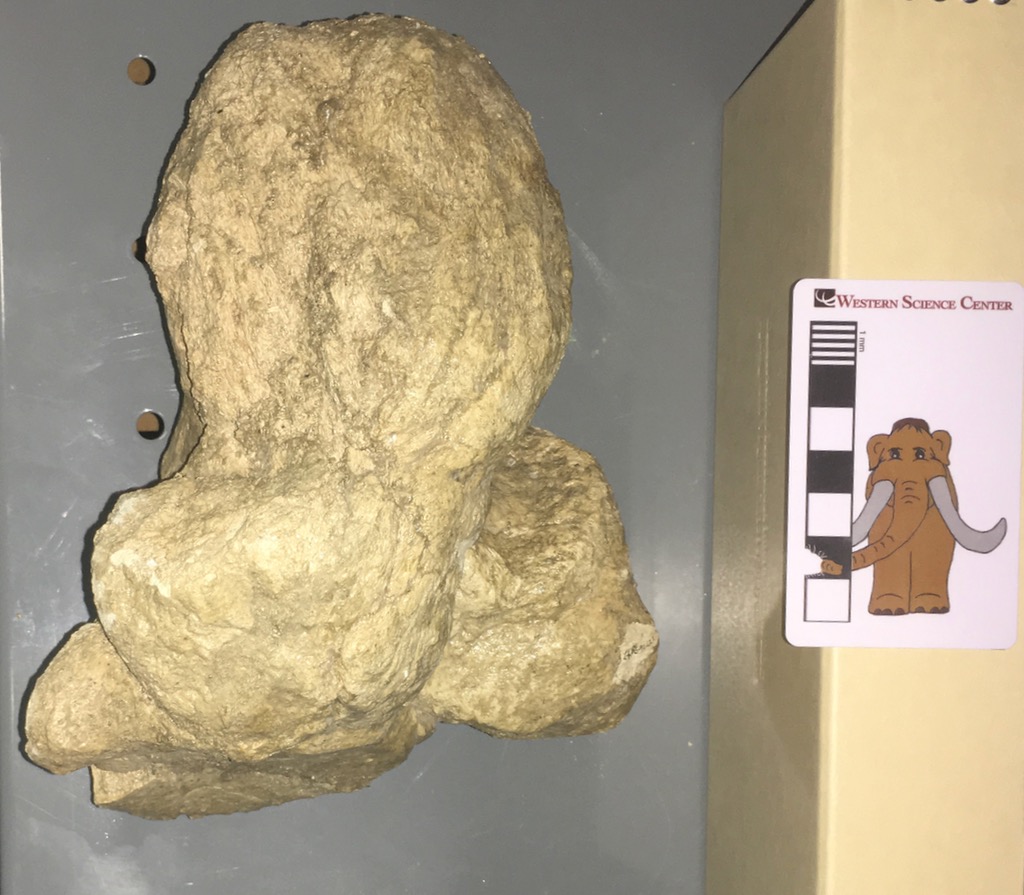

Continuing with our mastodon spree in preparation for next month's "Valley of the Mastodons" workshop and exhibit, this week for Fossil Friday we have a mastodon calcaneum.This is a left calcaneum, seen above in posterior view. The calcaneum is the heel bone, and together with the astragalus makes up the ankle joint. In anterior view (actually anterior and slightly ventral, below) the two bright white surfaces are the articulations with the astragalus:

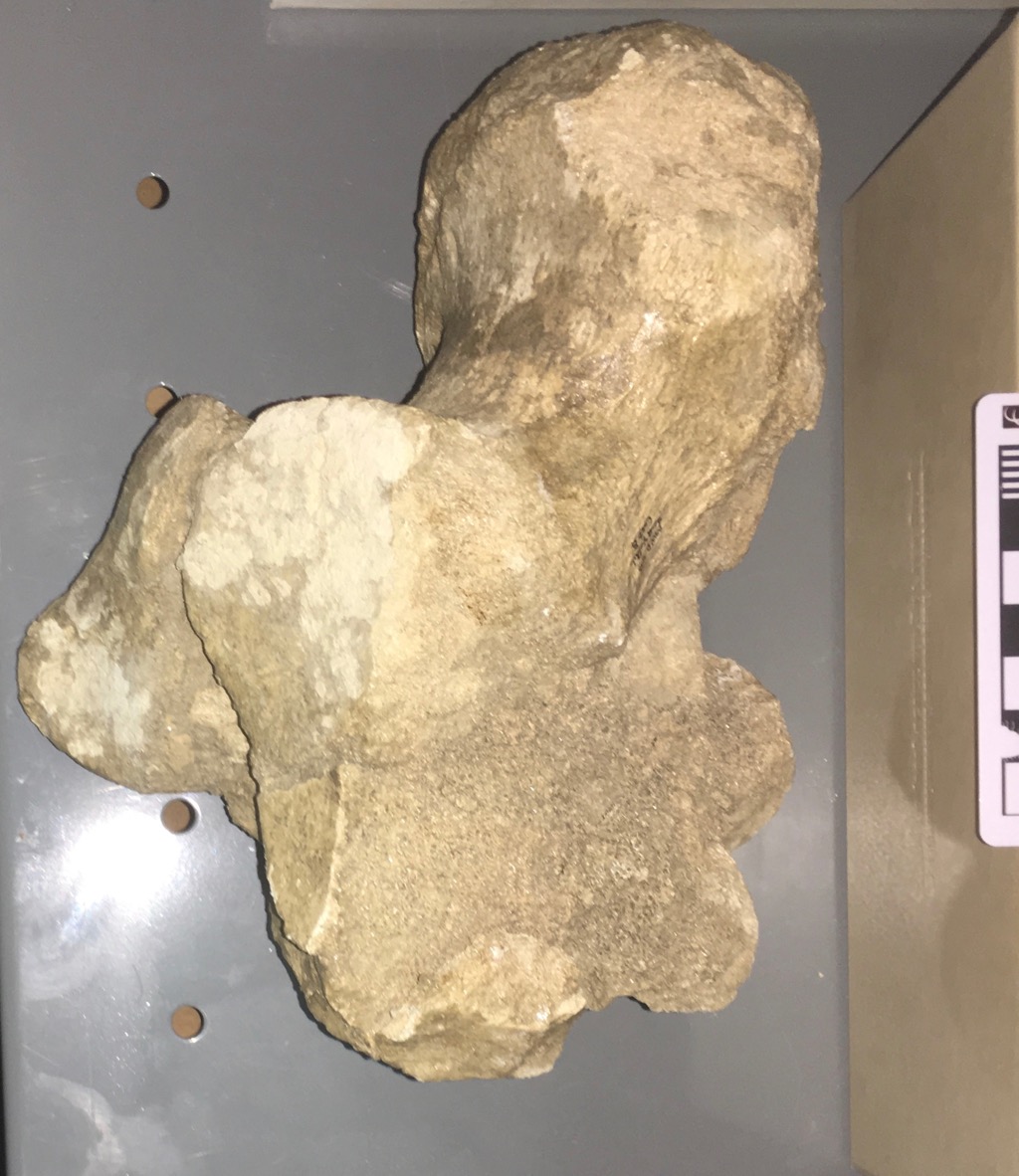

Continuing with our mastodon spree in preparation for next month's "Valley of the Mastodons" workshop and exhibit, this week for Fossil Friday we have a mastodon calcaneum.This is a left calcaneum, seen above in posterior view. The calcaneum is the heel bone, and together with the astragalus makes up the ankle joint. In anterior view (actually anterior and slightly ventral, below) the two bright white surfaces are the articulations with the astragalus: Here's a lateral view, with anterior to the left:

Here's a lateral view, with anterior to the left: The large mass of bone sticking off the top is called the tuber calcis. Humans are plantigrade animals, meaning that we walk with our feet on the ground. In our feet, the tuber calcis projects down and back, forming our heel. We actually walk on the bottom of the tuber calcis (covered with a thin layer of soft tissue), while various muscles attach to the top surface of the tuber calcis through the Achilles tendon. When these muscles flex the Achilles tendon pulls the tuber calcis up, rotating the foot down. When a ballerina stands en pointe, she is flexing these muscles and keeping the tuber calcis rotated up and forward.Most large mammals are not plantigrade but are instead digitigrade; they are en pointe all the time. However, different limb geometry means that they don't have to constantly flex a group of muscles to stay in that position. Instead, the foot between the ankle and toes acts like an additional leg segment, moving forward and backward at the ankle and held vertically when at rest. (Some people mistakenly believe that animals such as deer and horses have "backward knees"; they're actually looking at the ankle joint, not the knee.)Surprisingly, for all their bulk, proboscideans are digitigrade. Even though the toes are short and stout, the ankle is held high and the calcaneum is off the ground. (See these fantastic CT-based videos of elephant foot bones from What's in John's Freezer to see the relationships of the bones to each other.) When you look at an elephant's feet, it may not immediately be clear that they're digitigrade because there is a huge fatty pad that covers the palm and heel, turning the whole foot into a column. In the hind foot, the top back part of the fat pad is nestled under the calcaneum.Even with their thick, columnar legs, elephants have a fair range of mobility at the ankle, and can move their feet forward and back relative to the shin. This is consistent with the large tuber calcis, which remember serves as a muscle attachment point for pulling the foot back (in this case, pulling it back to the vertical, resting position). What is a bit surprising is that, compared to elephants and mammoths, the tuber calcis in mastodons is enormous, roughly twice as large. Perhaps foot strength and dexterity was more significant in mastodons for some reason?This calcaneum, along with hundreds of other mastodon bones, will be on display in the "Valley of the Mastodons" exhibit at the Western Science Center next month.

The large mass of bone sticking off the top is called the tuber calcis. Humans are plantigrade animals, meaning that we walk with our feet on the ground. In our feet, the tuber calcis projects down and back, forming our heel. We actually walk on the bottom of the tuber calcis (covered with a thin layer of soft tissue), while various muscles attach to the top surface of the tuber calcis through the Achilles tendon. When these muscles flex the Achilles tendon pulls the tuber calcis up, rotating the foot down. When a ballerina stands en pointe, she is flexing these muscles and keeping the tuber calcis rotated up and forward.Most large mammals are not plantigrade but are instead digitigrade; they are en pointe all the time. However, different limb geometry means that they don't have to constantly flex a group of muscles to stay in that position. Instead, the foot between the ankle and toes acts like an additional leg segment, moving forward and backward at the ankle and held vertically when at rest. (Some people mistakenly believe that animals such as deer and horses have "backward knees"; they're actually looking at the ankle joint, not the knee.)Surprisingly, for all their bulk, proboscideans are digitigrade. Even though the toes are short and stout, the ankle is held high and the calcaneum is off the ground. (See these fantastic CT-based videos of elephant foot bones from What's in John's Freezer to see the relationships of the bones to each other.) When you look at an elephant's feet, it may not immediately be clear that they're digitigrade because there is a huge fatty pad that covers the palm and heel, turning the whole foot into a column. In the hind foot, the top back part of the fat pad is nestled under the calcaneum.Even with their thick, columnar legs, elephants have a fair range of mobility at the ankle, and can move their feet forward and back relative to the shin. This is consistent with the large tuber calcis, which remember serves as a muscle attachment point for pulling the foot back (in this case, pulling it back to the vertical, resting position). What is a bit surprising is that, compared to elephants and mammoths, the tuber calcis in mastodons is enormous, roughly twice as large. Perhaps foot strength and dexterity was more significant in mastodons for some reason?This calcaneum, along with hundreds of other mastodon bones, will be on display in the "Valley of the Mastodons" exhibit at the Western Science Center next month.