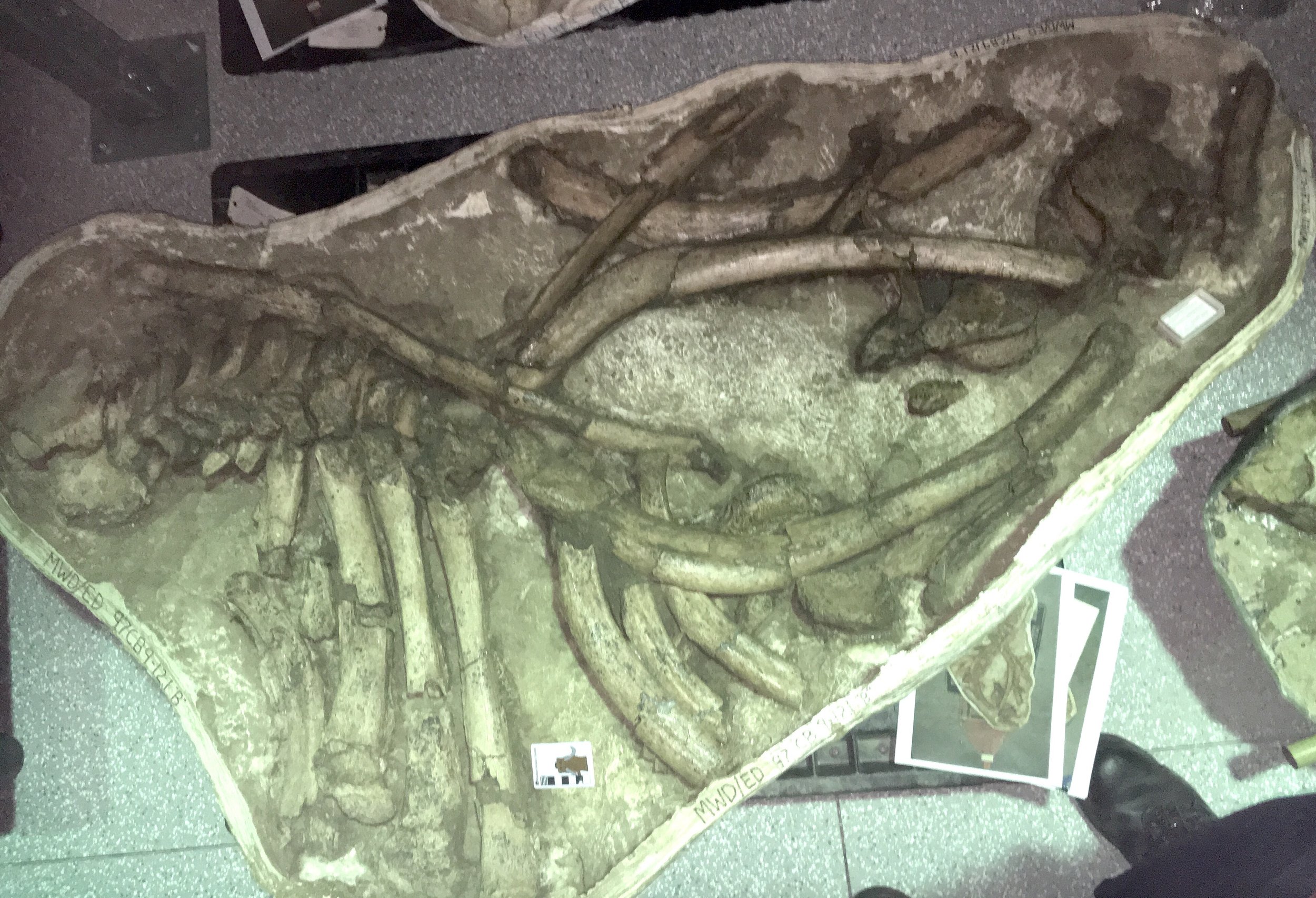

California mastodons have been in the news lately, so I decided to go with one of our Diamond Valley Lake mastodons for Fossil Friday this week.The specimen shown above is a partially articulated skeleton from the East Dam of the lake, making it among our older mastodon skeletons (likely at least 35,000 years old). In the marked version below, vertebrae are highlighted in blue:

California mastodons have been in the news lately, so I decided to go with one of our Diamond Valley Lake mastodons for Fossil Friday this week.The specimen shown above is a partially articulated skeleton from the East Dam of the lake, making it among our older mastodon skeletons (likely at least 35,000 years old). In the marked version below, vertebrae are highlighted in blue: The anterior end of the skeleton is to the left. The anterior end of the thoracic region is still pretty well articulated (it's possible this may include the last few cervical vertebrae, but confirming this will require closer examination). Further back, on the right, the skeleton becomes more scattered, and it appears a number of vertebrae are missing. The vertebra in the upper right corner is especially interesting; a closeup is below:

The anterior end of the skeleton is to the left. The anterior end of the thoracic region is still pretty well articulated (it's possible this may include the last few cervical vertebrae, but confirming this will require closer examination). Further back, on the right, the skeleton becomes more scattered, and it appears a number of vertebrae are missing. The vertebra in the upper right corner is especially interesting; a closeup is below: The rectangular vertebral centrum is typical of the posterior thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mastodons, and is quite different from the centrum shape in mammoths (which are taller and more pointed at the bottom), confirming the identity of this specimen as a mastodon.At least one of the ribs has notches along the margin that are consistent with marks caused by gnawing rodents:

The rectangular vertebral centrum is typical of the posterior thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mastodons, and is quite different from the centrum shape in mammoths (which are taller and more pointed at the bottom), confirming the identity of this specimen as a mastodon.At least one of the ribs has notches along the margin that are consistent with marks caused by gnawing rodents: Of course, the big media news this week was a report (Holen et al. 2017) of a 130,000-year-old mastodon from San Diego that was supposedly worked by humans, more than 100,000 years before humans were thought to have arrived in North America. I have read the paper and I'm currently reading the supplemental material. The paper is quite detailed, and while I'm impressed with their arguments I remain unconvinced of their interpretation. While I feel the age is likely correct, I question their interpretation that the damage seen on the bones could only have been caused by humans; there needs to be a much better demonstration that human activity is the only reasonable explanation for their observations. Human teeth, cranial bones, jaws, vertebrae, and limb elements are all easily identified, yet no scrap of human bone has turned up even in areas with extensive collections such as Diamond Valley Lake, even in 30-40,000 year old sediments that are young enough to date using C14. For what i's worth, while a few people have suggested otherwise, I see no eveidence of any human working of the Pleistocene bones from Diamond Valley Lake, and there's no evidence of human habitation from the Valley during the Ice Age, even though there are extensive archaeological remains in the Valley that post-date the Ice Age.

Of course, the big media news this week was a report (Holen et al. 2017) of a 130,000-year-old mastodon from San Diego that was supposedly worked by humans, more than 100,000 years before humans were thought to have arrived in North America. I have read the paper and I'm currently reading the supplemental material. The paper is quite detailed, and while I'm impressed with their arguments I remain unconvinced of their interpretation. While I feel the age is likely correct, I question their interpretation that the damage seen on the bones could only have been caused by humans; there needs to be a much better demonstration that human activity is the only reasonable explanation for their observations. Human teeth, cranial bones, jaws, vertebrae, and limb elements are all easily identified, yet no scrap of human bone has turned up even in areas with extensive collections such as Diamond Valley Lake, even in 30-40,000 year old sediments that are young enough to date using C14. For what i's worth, while a few people have suggested otherwise, I see no eveidence of any human working of the Pleistocene bones from Diamond Valley Lake, and there's no evidence of human habitation from the Valley during the Ice Age, even though there are extensive archaeological remains in the Valley that post-date the Ice Age.

Fossil Friday - possible mastodon bones

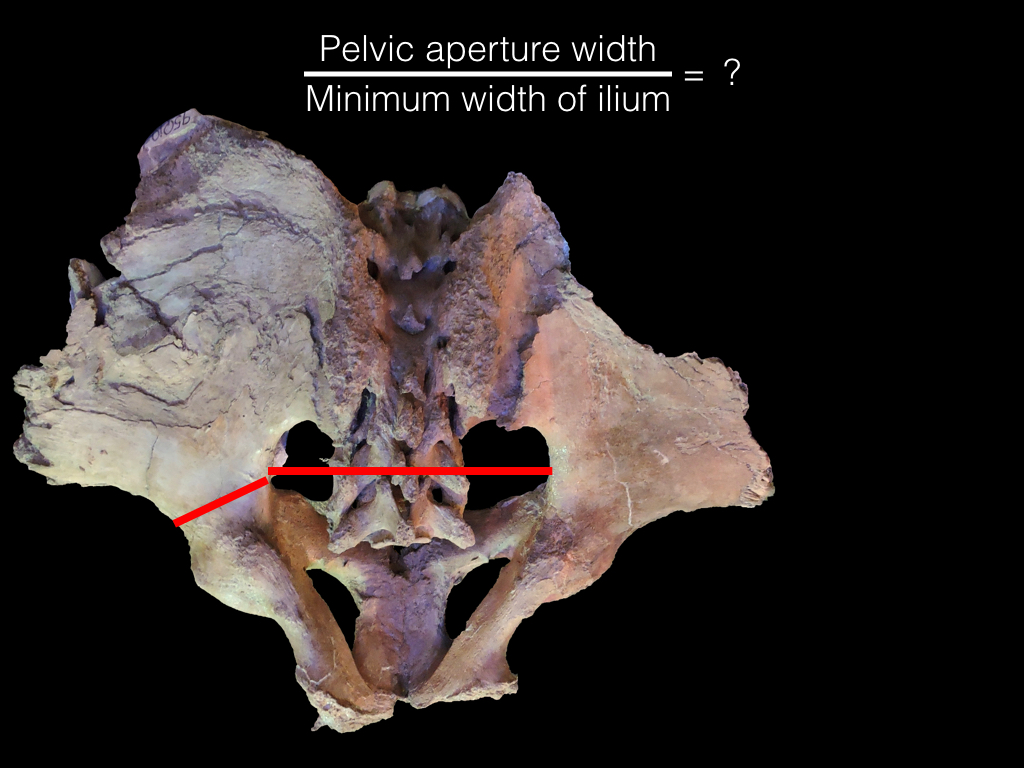

A common theme on this blog is that we can often get a lot of information from very incomplete material. Even so, as a general rule, the more remains we have from a given fossil organism, the more we can say about it. But sometimes we can have multiple bones, and even something as basic as a species identification can be elusive.The small field jacket shown above was collected from the West Dam of Diamond Valley Lake. There are several bones present, all consistent with a single individual. An annotated version is shown below:

A common theme on this blog is that we can often get a lot of information from very incomplete material. Even so, as a general rule, the more remains we have from a given fossil organism, the more we can say about it. But sometimes we can have multiple bones, and even something as basic as a species identification can be elusive.The small field jacket shown above was collected from the West Dam of Diamond Valley Lake. There are several bones present, all consistent with a single individual. An annotated version is shown below: The bone highlighted in blue is the distal end of the left femur. Those in red are ribs, the yellow are thoracic vertebrae, and the purple are unidentified. The size and general shape indicate that these are proboscidean bones, but there are two species from Diamond Valley Lake: the mammoth Mammuthus columbi and the mastodon Mammut americanum. While mastodons are much more common at DVL, numerous mammoth remains were also found. Which species is represented by these bones?Obviously our unidentified bones are not going to be of much help here. Ribs are also notoriously difficult to identify, especially if they're incomplete.The femur is potentially more useful. Femora have lots of distinctive features, and they differ between mammoths and mastodons. The most obvious difference is that mastodon femora are much more robust, while mammoth femora are rather long and slender. Unfortunately, this is difficult to evaluate unless a substantial portion of the femur (roughly half) is preserved. We only have about the distal fourth of the femur, and that is poorly preserved and partially hidden under the other bones. The medial condyle (the large curved knob at the end of the femur) does seem quite large, and this may suggest that a mastodon is more likely, but that's not much to go on.How about the vertebrae? In most vertebral positions mammoth and mastodon vertebrae are quite different. For example, in anterior view the lumbar vertebrae of mastodons have nearly rectangular centra that are wider than tall, while in mammoths they are more heart-shaped and are taller than wide. These vertebrae appear to be posterior thoracic vertebrae. Unfortunately, mammoth and mastodon posterior thoracics are very similar to each other. Mammoths tend to have much longer neural spines on these vertebrae, but the spines are incomplete in this specimen. Mastodons have a slightly taller and differently shaped neural canal, that seems a little more similar to these bones, but it seems this trait is quite variable.The only other hint may be the size. By proboscidean standards, these bones are not particularly large. Even though they're fairly small, they come from a more-or-less adult animal; the condyles are fused to the femur, and the vertebral epiphyses are fused to their centra, both of which indicate an animal that was mostly finished growing. Mammoths were larger than mastodons on average, so that suggests that a mastodon might be more likely (and, of course, mastodons are three times more common at DVL than mammoths).So, which is it? I don't know. I lean toward mastodon, and most of the observations seem to point that way, but that's with a lot of "mays", "seems", "suggests", and other tentative qualifiers. Sometimes, it's hard to say for sure.

The bone highlighted in blue is the distal end of the left femur. Those in red are ribs, the yellow are thoracic vertebrae, and the purple are unidentified. The size and general shape indicate that these are proboscidean bones, but there are two species from Diamond Valley Lake: the mammoth Mammuthus columbi and the mastodon Mammut americanum. While mastodons are much more common at DVL, numerous mammoth remains were also found. Which species is represented by these bones?Obviously our unidentified bones are not going to be of much help here. Ribs are also notoriously difficult to identify, especially if they're incomplete.The femur is potentially more useful. Femora have lots of distinctive features, and they differ between mammoths and mastodons. The most obvious difference is that mastodon femora are much more robust, while mammoth femora are rather long and slender. Unfortunately, this is difficult to evaluate unless a substantial portion of the femur (roughly half) is preserved. We only have about the distal fourth of the femur, and that is poorly preserved and partially hidden under the other bones. The medial condyle (the large curved knob at the end of the femur) does seem quite large, and this may suggest that a mastodon is more likely, but that's not much to go on.How about the vertebrae? In most vertebral positions mammoth and mastodon vertebrae are quite different. For example, in anterior view the lumbar vertebrae of mastodons have nearly rectangular centra that are wider than tall, while in mammoths they are more heart-shaped and are taller than wide. These vertebrae appear to be posterior thoracic vertebrae. Unfortunately, mammoth and mastodon posterior thoracics are very similar to each other. Mammoths tend to have much longer neural spines on these vertebrae, but the spines are incomplete in this specimen. Mastodons have a slightly taller and differently shaped neural canal, that seems a little more similar to these bones, but it seems this trait is quite variable.The only other hint may be the size. By proboscidean standards, these bones are not particularly large. Even though they're fairly small, they come from a more-or-less adult animal; the condyles are fused to the femur, and the vertebral epiphyses are fused to their centra, both of which indicate an animal that was mostly finished growing. Mammoths were larger than mastodons on average, so that suggests that a mastodon might be more likely (and, of course, mastodons are three times more common at DVL than mammoths).So, which is it? I don't know. I lean toward mastodon, and most of the observations seem to point that way, but that's with a lot of "mays", "seems", "suggests", and other tentative qualifiers. Sometimes, it's hard to say for sure.

Fossil Friday - worn mastodon tooth

Volunteer Joe Reavis been hard at work on a collection of fossils from a mitigation project in Murrieta that includes a lot of mastodon material. As far as we can tell so far, all of the mastodon material is consistent with one individual, although we did confirm yesterday that there is non-mastodon material in the same collection.The specimen shown above is a molar from a mastodon. It's in pretty rough shape, but I think it's the upper right second molar. If that's correct, then the occlusal view above has anterior at the top, and the lateral side of the tooth is on the left. The three loops of enamel on the left are the remnants of three lophs, which indicates that this is either a 4th premolar, 1st molar, or 2nd molar (the 2nd and 3rd premolars only have 2 lophs, and the 3rd molar has 4 or 5 lophs). The length of the tooth is comparable to other 2nd molars in our collection.Upper teeth in mastodons wear more rapidly on the medial side than the lateral side. If we look at this tooth in lateral view, we can see that there is a only about 2 cm of enamel remaining; the rest of the lophs have been worn away:

Volunteer Joe Reavis been hard at work on a collection of fossils from a mitigation project in Murrieta that includes a lot of mastodon material. As far as we can tell so far, all of the mastodon material is consistent with one individual, although we did confirm yesterday that there is non-mastodon material in the same collection.The specimen shown above is a molar from a mastodon. It's in pretty rough shape, but I think it's the upper right second molar. If that's correct, then the occlusal view above has anterior at the top, and the lateral side of the tooth is on the left. The three loops of enamel on the left are the remnants of three lophs, which indicates that this is either a 4th premolar, 1st molar, or 2nd molar (the 2nd and 3rd premolars only have 2 lophs, and the 3rd molar has 4 or 5 lophs). The length of the tooth is comparable to other 2nd molars in our collection.Upper teeth in mastodons wear more rapidly on the medial side than the lateral side. If we look at this tooth in lateral view, we can see that there is a only about 2 cm of enamel remaining; the rest of the lophs have been worn away: On the medial side, the wear is even more dramatic:

On the medial side, the wear is even more dramatic: If you're having a hard time telling what's going on here, it's because the enamel is completely gone. The tooth is worn all the way down into the tops of the roots.In most animals this would indicate that the animal was very old, but the horizontal tooth replacement in mastodons and most other proboscideans changes the equation. The 2nd molar typically wears away and falls out sometime around age 40 (very approximately). This tooth still had its roots (they were broken post-mortem), so this mastodon was probably around 40 years old when it died.

If you're having a hard time telling what's going on here, it's because the enamel is completely gone. The tooth is worn all the way down into the tops of the roots.In most animals this would indicate that the animal was very old, but the horizontal tooth replacement in mastodons and most other proboscideans changes the equation. The 2nd molar typically wears away and falls out sometime around age 40 (very approximately). This tooth still had its roots (they were broken post-mortem), so this mastodon was probably around 40 years old when it died.

Fossil Friday - mastodon molar

For the last few weeks, volunteer Joe Reavis has been diligently reconstructing a box of tooth fragments that came to the museum several years ago via a mitigation project in Murrieta, California. It quickly became apparent that the fragments were mastodon, and it seems they all come from a single tooth.The tooth is shown above in occlusal view, and the presence of four lophs show that it's a third molar. The angle of the lophs and comparison to other specimens in the WSC collection indicate that it's the upper left third molar.Here's the labial view:

For the last few weeks, volunteer Joe Reavis has been diligently reconstructing a box of tooth fragments that came to the museum several years ago via a mitigation project in Murrieta, California. It quickly became apparent that the fragments were mastodon, and it seems they all come from a single tooth.The tooth is shown above in occlusal view, and the presence of four lophs show that it's a third molar. The angle of the lophs and comparison to other specimens in the WSC collection indicate that it's the upper left third molar.Here's the labial view: And the lingual view:

And the lingual view: Looking past all the post-burial fracturing, this tooth shows no signs of any occlusal wear, and had probably not erupted. There is also enough preserved to get measurements for our "Mastodons of Unusual Size" project; the length:width ratio of this tooth is in the typical range for California specimens.The museum obtained several boxes of material from this site in Murrieta, but unfortunately it came with very little data or context. There is a fairly large amount of mastodon material included, including partial lower jaws with teeth and several limb elements, that are all consistent with a single individual. We're still in the process of preparing some of the other material.

Looking past all the post-burial fracturing, this tooth shows no signs of any occlusal wear, and had probably not erupted. There is also enough preserved to get measurements for our "Mastodons of Unusual Size" project; the length:width ratio of this tooth is in the typical range for California specimens.The museum obtained several boxes of material from this site in Murrieta, but unfortunately it came with very little data or context. There is a fairly large amount of mastodon material included, including partial lower jaws with teeth and several limb elements, that are all consistent with a single individual. We're still in the process of preparing some of the other material.

Fossil Friday - mastodon skull fragment

After the turmoil of end-of-year administrative duties, I'm now starting to turn my attention back to the Mastodons of Unusual Size Project.The subject of these week's Fossil Friday is a skull fragment that is being added to our dataset.The fragment is shown above in lateral view, with an annotated version below:

After the turmoil of end-of-year administrative duties, I'm now starting to turn my attention back to the Mastodons of Unusual Size Project.The subject of these week's Fossil Friday is a skull fragment that is being added to our dataset.The fragment is shown above in lateral view, with an annotated version below: While most of the skull is missing, there is a substantial part of the left front preserved, including the socket for the left tusk, the upper left 2nd molar, and part of the bottom edge of the eye socket. Below is a partial ventral view (part of this side is hidden by the plaster jacket:

While most of the skull is missing, there is a substantial part of the left front preserved, including the socket for the left tusk, the upper left 2nd molar, and part of the bottom edge of the eye socket. Below is a partial ventral view (part of this side is hidden by the plaster jacket: In this view it's clear that the 2nd molar is mostly intact. It's also quite heavily worn; this was a mature mastodon, probably almost as old as Max. It's 3rd molar should have been partially erupted, but that part of the skull is not preserved. The 2nd molar is 121 mm long, which is actually the longest M2 I've measured in a California specimen by a fairly large margin. But it's also only a little over 75 mm wide, making it unusually narrow even for a California specimen. The socket for the tusk is partially crushed, so I'm not confident about measurements of its diameter, but it seems on the small side; it's possible this is a female specimen.

In this view it's clear that the 2nd molar is mostly intact. It's also quite heavily worn; this was a mature mastodon, probably almost as old as Max. It's 3rd molar should have been partially erupted, but that part of the skull is not preserved. The 2nd molar is 121 mm long, which is actually the longest M2 I've measured in a California specimen by a fairly large margin. But it's also only a little over 75 mm wide, making it unusually narrow even for a California specimen. The socket for the tusk is partially crushed, so I'm not confident about measurements of its diameter, but it seems on the small side; it's possible this is a female specimen.

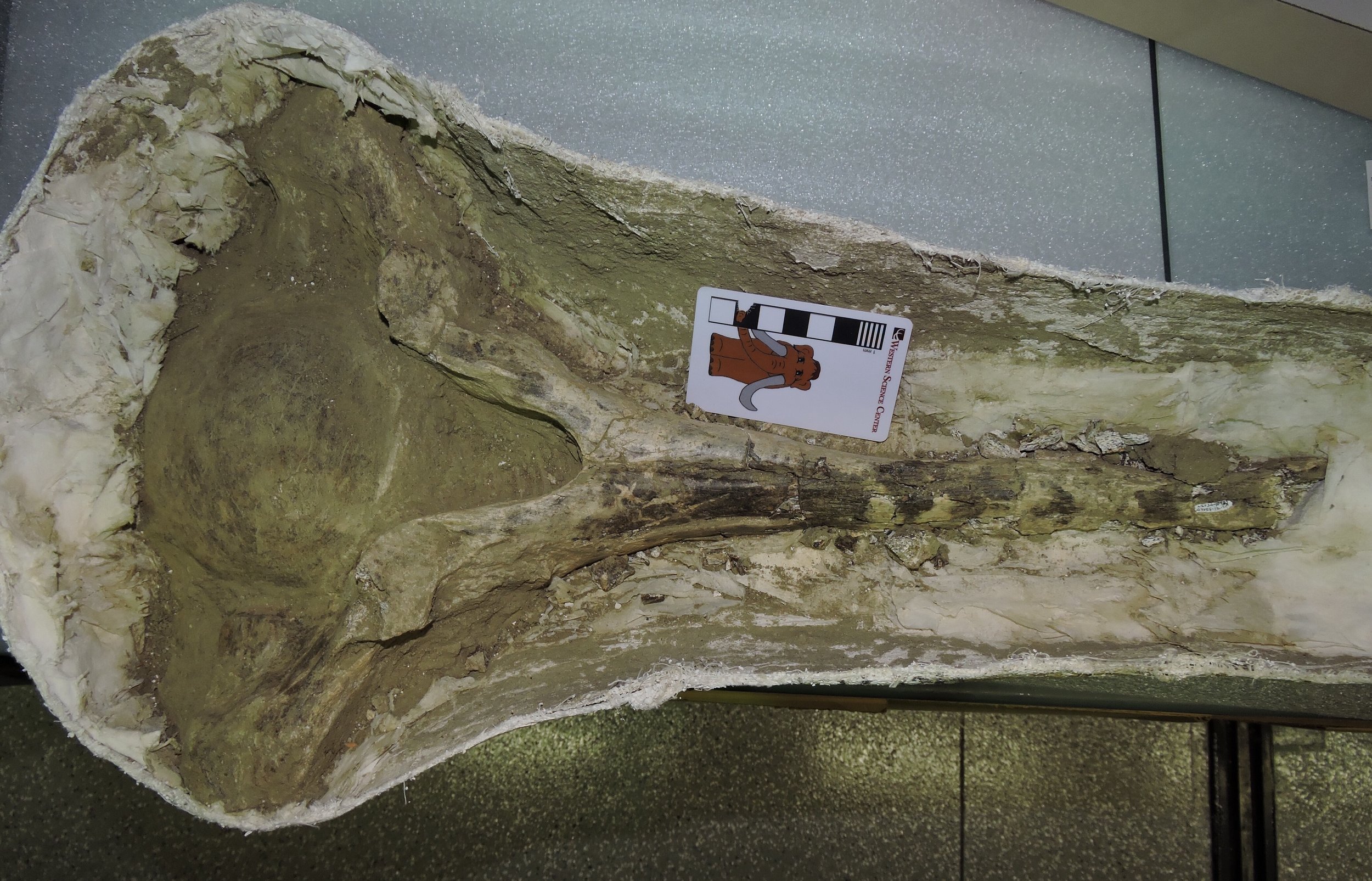

Fossil Friday - Proboscidean tusk

While the Diamond Valley Lake Project lasted for several years, it was still essentially a salvage operation. As a result, many of the larger specimens have only been partially prepared. Our staff and volunteers are gradually working through the backlog.For the last few months our volunteer Nathan has been reconstructing a shattered tusk, consisting of a tray with perhaps 300 fragments. His hard work is paying off, as a pretty nice tusk is beginning to take shape. More than half of recovered fragments have been reattached so far. We're not sure yet if this tusk is from a mammoth or a mastodon, although I'm leaning toward the latter. Assuming it is mastodon, it's either from an immature animal or from a female; adult male mastodons have massive tusks that are much larger than this. The tusk is worn at the tip, and there appears to be more than one wear facet. I'd like to say this indicates an older animal, but ivory is relatively soft and wears rapidly, so even a young animal can have substantial wear at the tip of the tusk.The DVL mastodon collection is dominated by adult males, and we don't have a lot of mammoths at any age, so this tusk represents a relatively rare part of the collection no matter what it ultimately turns out to be.

While the Diamond Valley Lake Project lasted for several years, it was still essentially a salvage operation. As a result, many of the larger specimens have only been partially prepared. Our staff and volunteers are gradually working through the backlog.For the last few months our volunteer Nathan has been reconstructing a shattered tusk, consisting of a tray with perhaps 300 fragments. His hard work is paying off, as a pretty nice tusk is beginning to take shape. More than half of recovered fragments have been reattached so far. We're not sure yet if this tusk is from a mammoth or a mastodon, although I'm leaning toward the latter. Assuming it is mastodon, it's either from an immature animal or from a female; adult male mastodons have massive tusks that are much larger than this. The tusk is worn at the tip, and there appears to be more than one wear facet. I'd like to say this indicates an older animal, but ivory is relatively soft and wears rapidly, so even a young animal can have substantial wear at the tip of the tusk.The DVL mastodon collection is dominated by adult males, and we don't have a lot of mammoths at any age, so this tusk represents a relatively rare part of the collection no matter what it ultimately turns out to be.

Fossil Friday - Max's pelvis revisited

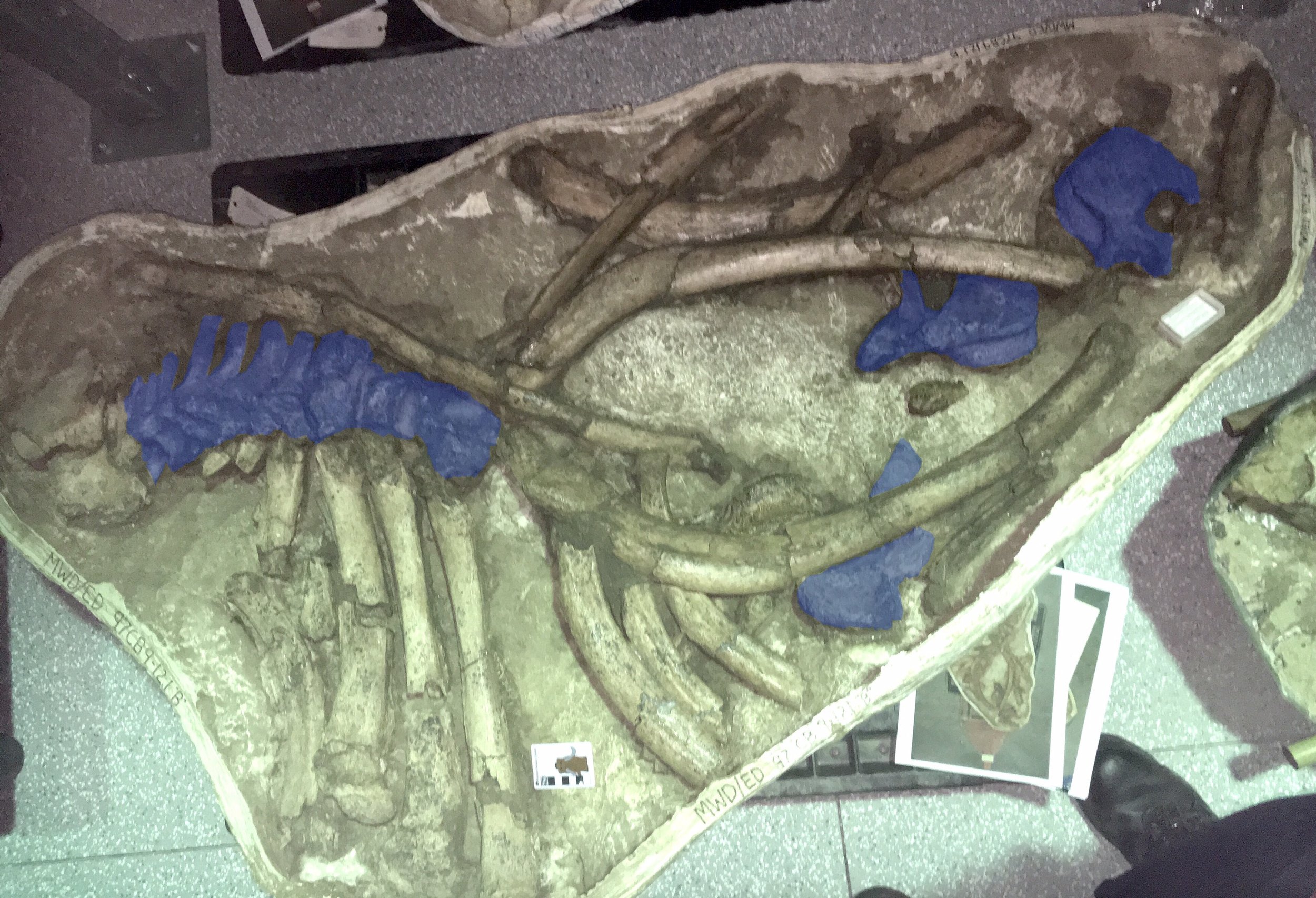

Western Science Center's largest mastodon, Max (@MaxMastodon on Twitter) has been getting a lot of attention over the last year. Besides getting CT scans and figuring prominently in the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" project, this October marks 21 years since Max was discovered. Max is also one of the WSC's major exhibits, and at our recent Science Under the Stars fundraiser we successfully raised funds to add new content to Max's (and other) displays, discussing some of the new things we've learned.Max is not only the largest mastodon known from California, but is also pretty large when compared to mastodons from other parts of the country, so we've long assumed he was male (male mastodons tend to be larger than females). But there are several parts of the skeleton where we can take direct measurements to have greater confidence when identifying Max's sex. One of these areas is the pelvis, which as I've discussed in a prior post is one of the well-preserved parts of Max.Lister (1996) showed that in mammoths males and females consistently differ in the ratio between two pelvic measurements, the pelvic aperture width and the minimum width of the ilial shaft, as shown in the image below:

Western Science Center's largest mastodon, Max (@MaxMastodon on Twitter) has been getting a lot of attention over the last year. Besides getting CT scans and figuring prominently in the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" project, this October marks 21 years since Max was discovered. Max is also one of the WSC's major exhibits, and at our recent Science Under the Stars fundraiser we successfully raised funds to add new content to Max's (and other) displays, discussing some of the new things we've learned.Max is not only the largest mastodon known from California, but is also pretty large when compared to mastodons from other parts of the country, so we've long assumed he was male (male mastodons tend to be larger than females). But there are several parts of the skeleton where we can take direct measurements to have greater confidence when identifying Max's sex. One of these areas is the pelvis, which as I've discussed in a prior post is one of the well-preserved parts of Max.Lister (1996) showed that in mammoths males and females consistently differ in the ratio between two pelvic measurements, the pelvic aperture width and the minimum width of the ilial shaft, as shown in the image below: In female mammoths, this ratio is greater than about 2.6, while it is less than 2.6 in males. Hodgson et al. (2008) and Fisher (2008) found that a similar relationship holds true for mastodons. In Max this ratio is 2.23, which is well on the male end of the spectrum. This is, of course, what we expected to find, but it's still necessary to go through the steps and confirm the results, rather than just assuming we'll get the expected answer.One of the new interactive stations funded by our Science Under the Stars fundraiser is going to feature the methods we used to determine Max's sex, including pelvic dimensions. Below is a draft video explanation of the pelvic measurements we put together for the fundraiser, narrated by WSC volunteer Catalina Lauridsen:[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zu4rOYtp9Ng]Tomorrow at WSC we're hosting the first Ice Age Soirée, and over-21 party celebrating 21 years since Max's discovery. Tickets are $40 and include dinner and drinks, as well as admission to the museum.References:Fisher, D. C., 2008. Taphonomy and paleobiology of the Hyde Park mastodon. In Allmon, W. D. and Nester, P. L., eds. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Paleontographica Americana 61:197-289.Hodgson, J. A., Allmon, W. D., Nester, P. L., Sherpa, J. M., and Chimney, J. J., 2008. Comparative osteology of Late Pleistocene mammoth and mastodon remains from the Watkins Glen Site, Chemung County, New York. In Allmon, W. D. and Nester, P. L., eds. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Paleontographica Americana 61:301-367.Lister, A. M., 1996. Sexual dimorphism in the mammoth pelvis: an aid to gender determination. In Shoshani, J. and Tassy, P. eds. The Proboscidea: Evolution and Paleoecology of Elephants and their Relatives. Oxford University Press, pp.254-259.

In female mammoths, this ratio is greater than about 2.6, while it is less than 2.6 in males. Hodgson et al. (2008) and Fisher (2008) found that a similar relationship holds true for mastodons. In Max this ratio is 2.23, which is well on the male end of the spectrum. This is, of course, what we expected to find, but it's still necessary to go through the steps and confirm the results, rather than just assuming we'll get the expected answer.One of the new interactive stations funded by our Science Under the Stars fundraiser is going to feature the methods we used to determine Max's sex, including pelvic dimensions. Below is a draft video explanation of the pelvic measurements we put together for the fundraiser, narrated by WSC volunteer Catalina Lauridsen:[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zu4rOYtp9Ng]Tomorrow at WSC we're hosting the first Ice Age Soirée, and over-21 party celebrating 21 years since Max's discovery. Tickets are $40 and include dinner and drinks, as well as admission to the museum.References:Fisher, D. C., 2008. Taphonomy and paleobiology of the Hyde Park mastodon. In Allmon, W. D. and Nester, P. L., eds. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Paleontographica Americana 61:197-289.Hodgson, J. A., Allmon, W. D., Nester, P. L., Sherpa, J. M., and Chimney, J. J., 2008. Comparative osteology of Late Pleistocene mammoth and mastodon remains from the Watkins Glen Site, Chemung County, New York. In Allmon, W. D. and Nester, P. L., eds. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Paleontographica Americana 61:301-367.Lister, A. M., 1996. Sexual dimorphism in the mammoth pelvis: an aid to gender determination. In Shoshani, J. and Tassy, P. eds. The Proboscidea: Evolution and Paleoecology of Elephants and their Relatives. Oxford University Press, pp.254-259.

Fossil Friday - seven bone fragments that built a museum

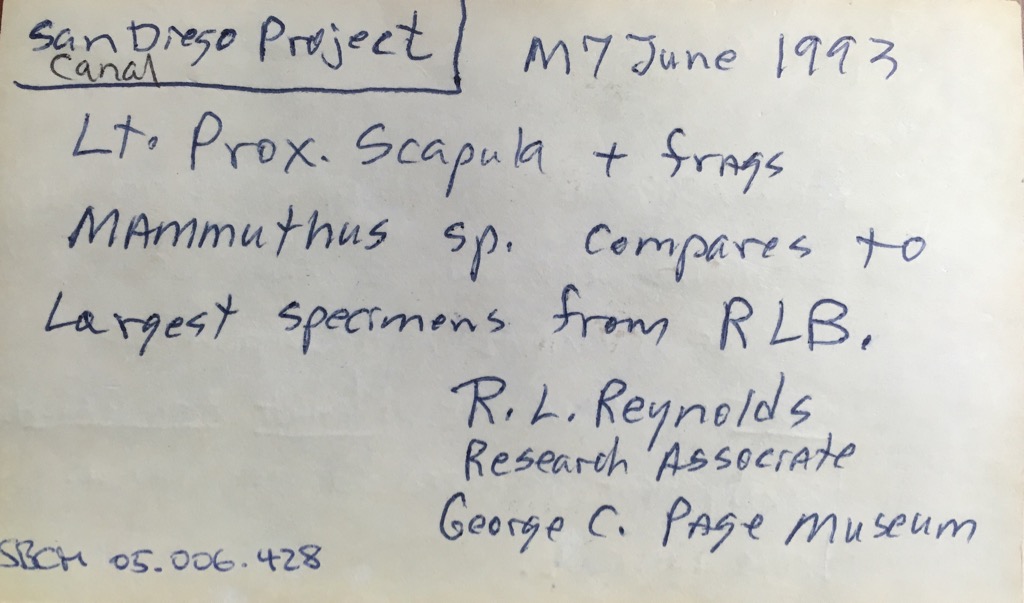

Tomorrow night the Western Science Center is holding the annual Science Under the Stars fundraiser. This year is a particularly special event, because the museum is celebrating its 10th anniversary; we opened to the public for the first time on October 15, 2006.WSC has grown over the last decade into a major regional museum and has brought in collections from a variety of locations, but the original reason we were founded was to house the collections recovered during the construction of Diamond Valley Lake and its related projects, such as the San Diego Canal and Domenigoni Parkway. These specimens still make up the majority of our collections.The seven bone fragments shown above we discovered by archaeologist Melinda Horne on 7 June 1993 along the path of the San Diego Canal. They don't look like much, but one thing is immediately obvious; they're pretty big fragments. The only animals found in California today (outside of zoos) that are even remotely close to being large enough to produce bones like these are horses and cows , and these fragments seem too large even for those. The largest fragment is a bit better preserved than the others; here's a different view:

Tomorrow night the Western Science Center is holding the annual Science Under the Stars fundraiser. This year is a particularly special event, because the museum is celebrating its 10th anniversary; we opened to the public for the first time on October 15, 2006.WSC has grown over the last decade into a major regional museum and has brought in collections from a variety of locations, but the original reason we were founded was to house the collections recovered during the construction of Diamond Valley Lake and its related projects, such as the San Diego Canal and Domenigoni Parkway. These specimens still make up the majority of our collections.The seven bone fragments shown above we discovered by archaeologist Melinda Horne on 7 June 1993 along the path of the San Diego Canal. They don't look like much, but one thing is immediately obvious; they're pretty big fragments. The only animals found in California today (outside of zoos) that are even remotely close to being large enough to produce bones like these are horses and cows , and these fragments seem too large even for those. The largest fragment is a bit better preserved than the others; here's a different view: The large, flat surface (where the number is painted) is an articular surface, where this bone articulated with another bone. Even though it's incomplete, there's enough preserved to identify this as the joint surface on the shoulder blade (technically, the glenoid fossa of the scapula). And that gives us another clue; this bone is far too large to be the glenoid fossa from a horse or a cow. The only common things in California this big are extinct Pleistocene elephants. This bone established the presence of Ice Age deposits in the area.This was noted by R. L. Reynolds from the George C. Page Museum, who tentatively identified the specimen as a mammoth, as written on an index card stored with the specimen:

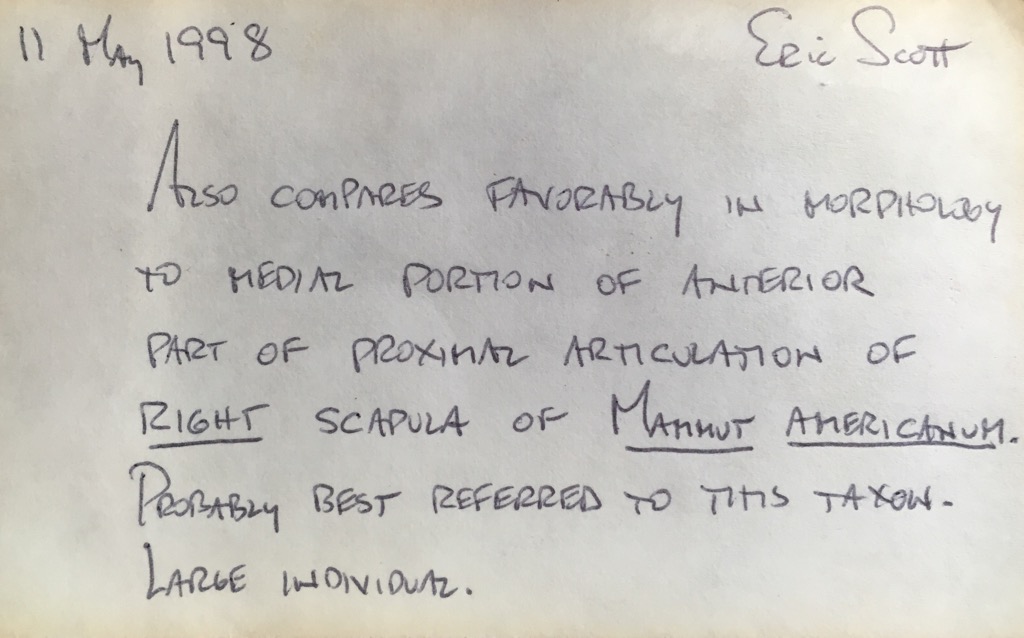

The large, flat surface (where the number is painted) is an articular surface, where this bone articulated with another bone. Even though it's incomplete, there's enough preserved to identify this as the joint surface on the shoulder blade (technically, the glenoid fossa of the scapula). And that gives us another clue; this bone is far too large to be the glenoid fossa from a horse or a cow. The only common things in California this big are extinct Pleistocene elephants. This bone established the presence of Ice Age deposits in the area.This was noted by R. L. Reynolds from the George C. Page Museum, who tentatively identified the specimen as a mammoth, as written on an index card stored with the specimen: Several years later, Eric Scott (who is now at the Cooper Center, and is one of my collaborators on the Mastodons of Unusual Size project), examined the specimen and considered it more likely to be from a mastodon than a mammoth (his notes were written on the back of the same index card):

Several years later, Eric Scott (who is now at the Cooper Center, and is one of my collaborators on the Mastodons of Unusual Size project), examined the specimen and considered it more likely to be from a mastodon than a mammoth (his notes were written on the back of the same index card): To give an idea of what Eric was seeing, here's a glenoid fossa view of the Watkins Glen mastodon from New York (this image is modified from Hodgson et al., 2008)...

To give an idea of what Eric was seeing, here's a glenoid fossa view of the Watkins Glen mastodon from New York (this image is modified from Hodgson et al., 2008)... ...and here's the same image with the California fragment scaled to the same size and superimposed:

...and here's the same image with the California fragment scaled to the same size and superimposed: That's a pretty good match, and I agree with Eric that this is probably from a mastodon, the first from the project.These seven fragments put paleontologists and engineers on alert that there could be additional Pleistocene fossils uncovered during the construction of the reservoir. As the project progressed, more specimens were uncovered, and 2 years after the initial find Max was discovered. Over the next decade more than 100,000 fossils were recovered in the area, a collection so large that a new museum was built to house it, and tomorrow night we'll celebrate that museum's tenth anniversary.A fossil doesn't have to look impressive to be important. Reference:Hodgson, J. A., W. D. Allmon, P. L. Nester, J. M. Sherpa, and J. J. Chimney, 2008. Comparative osteology of Late Pleistocene mammoth and mastodon remains from the Watkins Glen Site, Chemung County, New York. In Allmon, W. D. and P. L. Nester (eds.), 2008. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Palaeontographica Americana 61:301-367. Available for purchase.

That's a pretty good match, and I agree with Eric that this is probably from a mastodon, the first from the project.These seven fragments put paleontologists and engineers on alert that there could be additional Pleistocene fossils uncovered during the construction of the reservoir. As the project progressed, more specimens were uncovered, and 2 years after the initial find Max was discovered. Over the next decade more than 100,000 fossils were recovered in the area, a collection so large that a new museum was built to house it, and tomorrow night we'll celebrate that museum's tenth anniversary.A fossil doesn't have to look impressive to be important. Reference:Hodgson, J. A., W. D. Allmon, P. L. Nester, J. M. Sherpa, and J. J. Chimney, 2008. Comparative osteology of Late Pleistocene mammoth and mastodon remains from the Watkins Glen Site, Chemung County, New York. In Allmon, W. D. and P. L. Nester (eds.), 2008. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Palaeontographica Americana 61:301-367. Available for purchase.

Fossil Friday - mastodon skull

Today is World Elephant Day, recognizing the conservation difficulties faced by the surviving species of elephants. Last week, with Katy Smith's visit to WSC to examine mastodons and Bernard Means' visit to 3D-scan some of our specimens, as well as needing more data for the Mastodons of Unusual Size Project, we had the opportunity and motivation to open a lot of mastodon jackets that have remained unexamined for years. This confluence of events make an excellent excuse for featuring another mastodon for today's Fossil Friday.It turns out that, as much as I've touted the mastodon collection at WSC, it's even better than I had realized. Shown above is one of several partial skulls we examined last week. The skull is oriented ventral up, so the palate side is visible; the lower jaw is not preserved. Anterior is to the top of the image. The two large tusks are essentially complete, as is the ventral side of the premaxillary bone that supports them. A small portion of the maxilla is preserved, which includes both upper second molars and the anterior portions of the third molars, which are more clear in the image below:

Today is World Elephant Day, recognizing the conservation difficulties faced by the surviving species of elephants. Last week, with Katy Smith's visit to WSC to examine mastodons and Bernard Means' visit to 3D-scan some of our specimens, as well as needing more data for the Mastodons of Unusual Size Project, we had the opportunity and motivation to open a lot of mastodon jackets that have remained unexamined for years. This confluence of events make an excellent excuse for featuring another mastodon for today's Fossil Friday.It turns out that, as much as I've touted the mastodon collection at WSC, it's even better than I had realized. Shown above is one of several partial skulls we examined last week. The skull is oriented ventral up, so the palate side is visible; the lower jaw is not preserved. Anterior is to the top of the image. The two large tusks are essentially complete, as is the ventral side of the premaxillary bone that supports them. A small portion of the maxilla is preserved, which includes both upper second molars and the anterior portions of the third molars, which are more clear in the image below: The proximal end of one femur is also preserved; it's the lump of bone in the foreground.The most notable thing about this skull is the black coloring over much of the surface, including almost all of the left tusk. It appears that this specimen was burned, almost certainly after death. We see this in a fair number of bones from Diamond Valley Lake, but it's the first time we've noted it in a mastodon, leading our Marketing Specialist Brittney Stoneburg to nickname this specimen "Blaze".Blaze is missing most of his third molars, but his second molars are intact and we were able to get measurements for the Mastodons of Unusual Size Project. Katy was also able to get measurements for her studies on mastodon tusks (and, based on the size of the tusks, Blaze was almost certainly a male). Blaze's second molars were heavily worn, and the anterior portions of his third molars were in wear, suggesting that he was close to the same age as Max when he died, perhaps in his mid-30s.Today on World Elephant Day, help support elephant conservation by visiting or donating to a museum, zoo, or conservation group that furthers our knowledge and protection of these amazing animals.

The proximal end of one femur is also preserved; it's the lump of bone in the foreground.The most notable thing about this skull is the black coloring over much of the surface, including almost all of the left tusk. It appears that this specimen was burned, almost certainly after death. We see this in a fair number of bones from Diamond Valley Lake, but it's the first time we've noted it in a mastodon, leading our Marketing Specialist Brittney Stoneburg to nickname this specimen "Blaze".Blaze is missing most of his third molars, but his second molars are intact and we were able to get measurements for the Mastodons of Unusual Size Project. Katy was also able to get measurements for her studies on mastodon tusks (and, based on the size of the tusks, Blaze was almost certainly a male). Blaze's second molars were heavily worn, and the anterior portions of his third molars were in wear, suggesting that he was close to the same age as Max when he died, perhaps in his mid-30s.Today on World Elephant Day, help support elephant conservation by visiting or donating to a museum, zoo, or conservation group that furthers our knowledge and protection of these amazing animals.

Fossil Friday - associated mastodon material

This week we have two visiting researchers at Western Science Center. Dr. Katy Smith from Georgia Southern University has been measuring and photographing the proboscidean tusks in our collection, which we hope will lead to all kinds of new information about southern California mastodons and mammoths. Dr. Bernard Means from Virginia Commonwealth University's Virtual Curation Lab has been here on a trip sponsored by Smithsonian Affiliations to make 3D scans of some of the WSC specimens (Bernard has written about his visit here). These visits have meant that we've been pulling out lots of specimens, many of which I had never seen before.Last June I wrote about one of our mastodon jaws, which is an interesting specimen for the Mastodons of Unusual Size project because of its outlier status. This mastodon has the widest lower third molars we've measured in any California specimen, by a pretty large margin. As it turns out (and unknown to me until this week), we have part of the cranium from the same specimen.In the image above, the cranium fragment is sitting beside the lower jaw, and facing the opposite direction, so anterior is to the left. The fragment consists mostly of the left premaxilla and maxilla with the associated teeth. The rather large left tusk suggests that this was a male mastodon (the distal end of the tusk is broken off). The left second and third molars are both well preserved, with the second molar fully in wear and the third molar just starting to erupt, suggesting he was in his early 20's (and consistent with the lower jaw tooth wear).It turns out the upper third molars are outliers, but not quite to the same degree as the lower molars. We have several California upper M3s that are wider than this tooth, but those teeth are also much longer than this one. That means that the proportions of this tooth are unusual for California, even though we have teeth that are both longer and wider than this one. In fact, there's a tooth in our database from Ohio that is almost exactly the same dimensions as this one.

This week we have two visiting researchers at Western Science Center. Dr. Katy Smith from Georgia Southern University has been measuring and photographing the proboscidean tusks in our collection, which we hope will lead to all kinds of new information about southern California mastodons and mammoths. Dr. Bernard Means from Virginia Commonwealth University's Virtual Curation Lab has been here on a trip sponsored by Smithsonian Affiliations to make 3D scans of some of the WSC specimens (Bernard has written about his visit here). These visits have meant that we've been pulling out lots of specimens, many of which I had never seen before.Last June I wrote about one of our mastodon jaws, which is an interesting specimen for the Mastodons of Unusual Size project because of its outlier status. This mastodon has the widest lower third molars we've measured in any California specimen, by a pretty large margin. As it turns out (and unknown to me until this week), we have part of the cranium from the same specimen.In the image above, the cranium fragment is sitting beside the lower jaw, and facing the opposite direction, so anterior is to the left. The fragment consists mostly of the left premaxilla and maxilla with the associated teeth. The rather large left tusk suggests that this was a male mastodon (the distal end of the tusk is broken off). The left second and third molars are both well preserved, with the second molar fully in wear and the third molar just starting to erupt, suggesting he was in his early 20's (and consistent with the lower jaw tooth wear).It turns out the upper third molars are outliers, but not quite to the same degree as the lower molars. We have several California upper M3s that are wider than this tooth, but those teeth are also much longer than this one. That means that the proportions of this tooth are unusual for California, even though we have teeth that are both longer and wider than this one. In fact, there's a tooth in our database from Ohio that is almost exactly the same dimensions as this one.

Mastodons of Unusual Size - Denver Museum of Nature and Science

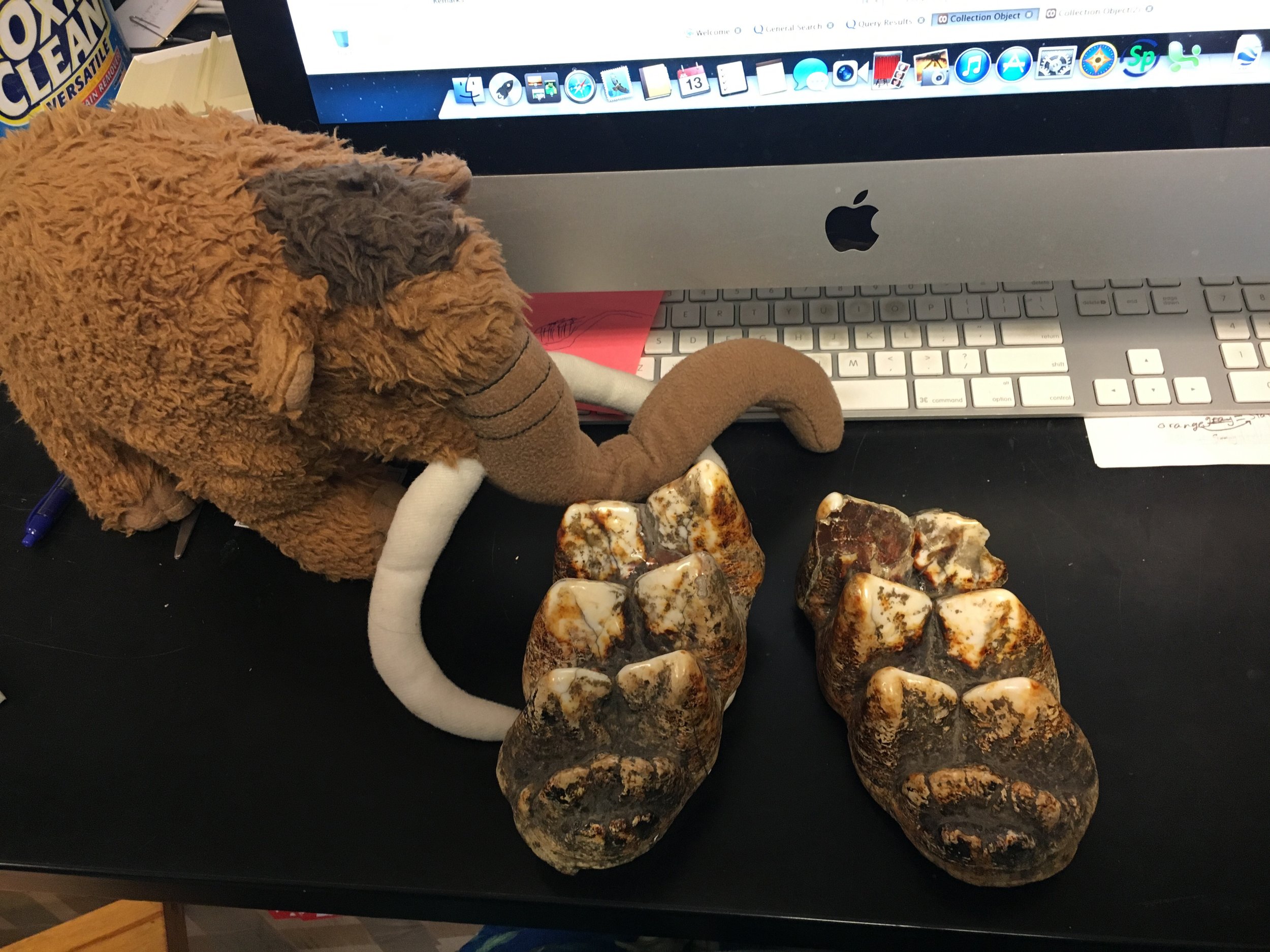

On Thursday Brett, Max, and I made our sixth stop on the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" tour, at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.The major reason for stopping in Denver was to examine specimens from the Snowmastodon Project. In 2010 during the construction of a reservoir at Snowmass Village several thousand Ice Age fossils were discovered. There were two especially remarkable features at the site. First, at an altitude of over 8,800 feet, it was one of the highest Ice Age deposits ever found. Second, by far the most common animals were mastodons, accounting for more than half of the bones recovered. From the Rocky Mountains west to the Pacific Ocean, the vast majority of known mastodons come from just three sites - Snowmass Village, Rancho La Brea, and Diamond Valkey Lake.There are a number of very well-preserved crania and mandibles from Snowmass in the Denver collection (Max is seen above with some of the mandibles), that range from very young, perhaps even fetal, animals to an individual that was so old that its last tooth was worn to the roots (we couldn't measure that one because there wasn't enough tooth left!):

On Thursday Brett, Max, and I made our sixth stop on the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" tour, at the Denver Museum of Nature and Science.The major reason for stopping in Denver was to examine specimens from the Snowmastodon Project. In 2010 during the construction of a reservoir at Snowmass Village several thousand Ice Age fossils were discovered. There were two especially remarkable features at the site. First, at an altitude of over 8,800 feet, it was one of the highest Ice Age deposits ever found. Second, by far the most common animals were mastodons, accounting for more than half of the bones recovered. From the Rocky Mountains west to the Pacific Ocean, the vast majority of known mastodons come from just three sites - Snowmass Village, Rancho La Brea, and Diamond Valkey Lake.There are a number of very well-preserved crania and mandibles from Snowmass in the Denver collection (Max is seen above with some of the mandibles), that range from very young, perhaps even fetal, animals to an individual that was so old that its last tooth was worn to the roots (we couldn't measure that one because there wasn't enough tooth left!): With such a large mastodon sample, we were able to measure teeth from every position and a variety of different ages. This tiny maxilla fragment preserves the first two teeth, the second and third premolars:

With such a large mastodon sample, we were able to measure teeth from every position and a variety of different ages. This tiny maxilla fragment preserves the first two teeth, the second and third premolars: This maxilla has the third and fourth premolars:

This maxilla has the third and fourth premolars: And below is a maxilla fragment with the next three teeth, the first, second, and third molars all preserved:

And below is a maxilla fragment with the next three teeth, the first, second, and third molars all preserved:  Some of the Snowmass specimens are true giants. We measured one femur (actually the cast, below) that had a distal width 11% greater than Max's:

Some of the Snowmass specimens are true giants. We measured one femur (actually the cast, below) that had a distal width 11% greater than Max's: The Snowmass sample was an excellent addition to our dataset, but there were actually a few other mastodons in the DMNH collections. Below is apparently the only known mastodon tooth from Colorado that wasn't found at Snowmass:

The Snowmass sample was an excellent addition to our dataset, but there were actually a few other mastodons in the DMNH collections. Below is apparently the only known mastodon tooth from Colorado that wasn't found at Snowmass: There is also an Indiana mastodon in the Denver collections. This specimen has femora that are slightly larger than Max's, and relatively rare 5-lophid lower third molars:

There is also an Indiana mastodon in the Denver collections. This specimen has femora that are slightly larger than Max's, and relatively rare 5-lophid lower third molars:  We spent seven straight hours in the Denver collections, measuring 85 mastodon teeth. It's going to take awhile for me to sort through everything and see what we have, but a few initial impressions did jump out at me. Most significantly, the Snowmass mastodons don't seem to look much like the California mastodons. Almost none of the third molars have a length:width ratio of greater than 2 (I think only one specimen), while almost every California mastodon has a ratio greater than 2. More strikingly, it seems that every Snowmass mastodon had lower tusks (as seen below), a feature that has never been observed in a California mastodon.

We spent seven straight hours in the Denver collections, measuring 85 mastodon teeth. It's going to take awhile for me to sort through everything and see what we have, but a few initial impressions did jump out at me. Most significantly, the Snowmass mastodons don't seem to look much like the California mastodons. Almost none of the third molars have a length:width ratio of greater than 2 (I think only one specimen), while almost every California mastodon has a ratio greater than 2. More strikingly, it seems that every Snowmass mastodon had lower tusks (as seen below), a feature that has never been observed in a California mastodon. As I write this, Brett, Max, and I are on our way home to California. But this doesn't mark the end of "Mastodons of Unusual Size". We are still gathering data that's being supplied by other researchers, and still collecting data on California mastodons (we haven't even measured all the Diamond Valley Lake specimens yet). In October we'll be presenting our preliminary results at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Salt Lake City. And, of course, I'll be posing updates on our progress here, on Twitter, and at experiment.com.Thanks to all the curators and collections managers who provided access to the collections in their care, and to our experiment.com donors that made this trip possible.

As I write this, Brett, Max, and I are on our way home to California. But this doesn't mark the end of "Mastodons of Unusual Size". We are still gathering data that's being supplied by other researchers, and still collecting data on California mastodons (we haven't even measured all the Diamond Valley Lake specimens yet). In October we'll be presenting our preliminary results at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Salt Lake City. And, of course, I'll be posing updates on our progress here, on Twitter, and at experiment.com.Thanks to all the curators and collections managers who provided access to the collections in their care, and to our experiment.com donors that made this trip possible.

Fossil Friday - mastodon astragalus

I'm still on the experiment.com-funded Mastodons of Unusual Size tour, and will be doing an additional post on that tomorrow. My inability to type and drive at the same time means I can only do a short Fossil Friday post.The bone shown above is a mastodon astragalus, the most proximal of the ankle bones. The upper end of the astragalus articulates with the lower ends of the shin bones (the tibia and fibula), although in elephants the amount of movement at that joint is limited. Proboscidean ankle bones are much less complex than in most other animals, and are optimized for weight-bearing. Interestingly, it seems that some dwarfed elephants evolved a rather different ankle structure for walking in hilly terrain.This astragalus was found at the East Dam of Diamond Valley Lake.

I'm still on the experiment.com-funded Mastodons of Unusual Size tour, and will be doing an additional post on that tomorrow. My inability to type and drive at the same time means I can only do a short Fossil Friday post.The bone shown above is a mastodon astragalus, the most proximal of the ankle bones. The upper end of the astragalus articulates with the lower ends of the shin bones (the tibia and fibula), although in elephants the amount of movement at that joint is limited. Proboscidean ankle bones are much less complex than in most other animals, and are optimized for weight-bearing. Interestingly, it seems that some dwarfed elephants evolved a rather different ankle structure for walking in hilly terrain.This astragalus was found at the East Dam of Diamond Valley Lake.

Mastodons of Unusual Size - University of Wyoming

Yesterday we made our fifth stop on the Mastodons of Unusual Size tour, the University of Wyoming Geological Museum in Laramie. Mastodons get increasingly scarce as you move west, but we had hopes that something would turn up in the excellent fossil mammal collections at the Geological Museum.With the help of Collections Manager Laura Vietti, we tracked down the only two teeth in the Geological Museum's collection, shown above with Max. Both of these teeth are lower third molars, but unfortunately the first lophid is missing on each tooth, so we weren't able to get measurements on either one. Even more surprising, it appears that both teeth are originally from Illinois. With these teeth ruled out, it appears that there are no known mastodon specimens from Wyoming!This is actually interesting news for us, because lots of Pleistocene animals from other species have been found in Wyoming over the years. If mastodons were common there, they should have been found by now, so it seems they were almost certainly absent or at least very rare in Wyoming. Interestingly, when I was planning this trip I contacted the South Dakota School of Mines Geological Museum in nearby Rapid City, which also holds lots of fossil mammals, only to be told that while their collections included lots of mammoths, they didn't have any mastodons at all. It seems that mastodons may have almost entirely avoided the high plains.Yesterday afternoon we left Laramie and headed to Denver for our next stop. More on that to come!

Yesterday we made our fifth stop on the Mastodons of Unusual Size tour, the University of Wyoming Geological Museum in Laramie. Mastodons get increasingly scarce as you move west, but we had hopes that something would turn up in the excellent fossil mammal collections at the Geological Museum.With the help of Collections Manager Laura Vietti, we tracked down the only two teeth in the Geological Museum's collection, shown above with Max. Both of these teeth are lower third molars, but unfortunately the first lophid is missing on each tooth, so we weren't able to get measurements on either one. Even more surprising, it appears that both teeth are originally from Illinois. With these teeth ruled out, it appears that there are no known mastodon specimens from Wyoming!This is actually interesting news for us, because lots of Pleistocene animals from other species have been found in Wyoming over the years. If mastodons were common there, they should have been found by now, so it seems they were almost certainly absent or at least very rare in Wyoming. Interestingly, when I was planning this trip I contacted the South Dakota School of Mines Geological Museum in nearby Rapid City, which also holds lots of fossil mammals, only to be told that while their collections included lots of mammoths, they didn't have any mastodons at all. It seems that mastodons may have almost entirely avoided the high plains.Yesterday afternoon we left Laramie and headed to Denver for our next stop. More on that to come!

Mastodons of Unusual Size - Joseph Moore Museum

This morning Brett, Max, and I visited the next museum on the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" tour, the Joseph Moore Museum at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana.The Joseph Moore Museum has a small but significant collection of Pleistocene fossils, with a mounted mastodon composite skeleton (above) as one of the centerpiece exhibits. Unfortunately, the teeth on this specimen are damaged and couldn't be measured, but there were several other mastodon teeth in the collection.

This morning Brett, Max, and I visited the next museum on the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" tour, the Joseph Moore Museum at Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana.The Joseph Moore Museum has a small but significant collection of Pleistocene fossils, with a mounted mastodon composite skeleton (above) as one of the centerpiece exhibits. Unfortunately, the teeth on this specimen are damaged and couldn't be measured, but there were several other mastodon teeth in the collection. The tooth shown above, from Indiana, is a fairly typical lower third molar, with four lophids (the transverse enamel ridges) and a large posterior cingulid (the bumpy ridge at the back of the tooth that looks like a small lophid on the right in the image). Compare this to from another one in the Joseph Moore Museum collection below, from Ohio:

The tooth shown above, from Indiana, is a fairly typical lower third molar, with four lophids (the transverse enamel ridges) and a large posterior cingulid (the bumpy ridge at the back of the tooth that looks like a small lophid on the right in the image). Compare this to from another one in the Joseph Moore Museum collection below, from Ohio: This one is also a lower third molar, but this one has five lophids, and still has a posterior cingulid (posterior is on the left in this image). The five lophid morphology seems to show up in a small percentage of mastodons; we've seen it in only a few specimens so far on this trip, so it nice to find this one at Earlham.We were able to add five teeth to our dataset on this visit. Thanks to JMM Director Heather Lerner for providing access to Earlham's collection.

This one is also a lower third molar, but this one has five lophids, and still has a posterior cingulid (posterior is on the left in this image). The five lophid morphology seems to show up in a small percentage of mastodons; we've seen it in only a few specimens so far on this trip, so it nice to find this one at Earlham.We were able to add five teeth to our dataset on this visit. Thanks to JMM Director Heather Lerner for providing access to Earlham's collection.

Mastodons of Unusual Size - Boonshoft Museum of Discovery

Brett, Max, and I headed back into Ohio this morning for our next stop on the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" tour; the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery in Dayton.The most impressive Boonshoft mastodon is a more-or-less complete skull, shown above with Max. This was a young adult animal, perhaps 16-20 years old based on tooth wear. The first and second molars were erupted and functional, but the third molars had not yet erupted (the tooth eruption stage is very close to that of Xena, the Columbian mammoth on exhibit at WSC). This specimen also includes some postcranial bones, including both femora (below is the right one in anterior view):

Brett, Max, and I headed back into Ohio this morning for our next stop on the "Mastodons of Unusual Size" tour; the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery in Dayton.The most impressive Boonshoft mastodon is a more-or-less complete skull, shown above with Max. This was a young adult animal, perhaps 16-20 years old based on tooth wear. The first and second molars were erupted and functional, but the third molars had not yet erupted (the tooth eruption stage is very close to that of Xena, the Columbian mammoth on exhibit at WSC). This specimen also includes some postcranial bones, including both femora (below is the right one in anterior view): The presence of the femora is nice because they give us a data point for comparing tooth size to body size.Below is simultaneously the most intriguing and frustrating specimen we saw today:

The presence of the femora is nice because they give us a data point for comparing tooth size to body size.Below is simultaneously the most intriguing and frustrating specimen we saw today: This small lower third molar has both the size and proportions we would normally expect to see in a California mastodon. So, is this an Ohio specimen that looks like a Californian one? Maybe not! The Boonshoft has a few specimens acquired nearly 100 years ago from Rancho La Brea. This tooth has black residue on it that looks a lot like Rancho La Brea sediment. But...the specimen has no locality information, so we can't confirm where it's from (at least not without some expensive chemical testing)!We examined 17 teeth in the Boonshoft collection, which came from nine individuals; 4 of these teeth didn't have locality data and probably can't be included in our study. Most of the specimens are from Ohio, but we also examined a lower jaw from Florida. The addition of a skull with associated femora is significant, and prior to our Cincinnati and Boonshoft visits we had almost no Ohio or Kentucky specimens in our database. Thanks to Boonshoft's Anthropology Curator Bill Kennedy (below, with Max) for helping us with access to the collections.Tomorrow "Mastodons of Unusual Size" continues with our next stop.

This small lower third molar has both the size and proportions we would normally expect to see in a California mastodon. So, is this an Ohio specimen that looks like a Californian one? Maybe not! The Boonshoft has a few specimens acquired nearly 100 years ago from Rancho La Brea. This tooth has black residue on it that looks a lot like Rancho La Brea sediment. But...the specimen has no locality information, so we can't confirm where it's from (at least not without some expensive chemical testing)!We examined 17 teeth in the Boonshoft collection, which came from nine individuals; 4 of these teeth didn't have locality data and probably can't be included in our study. Most of the specimens are from Ohio, but we also examined a lower jaw from Florida. The addition of a skull with associated femora is significant, and prior to our Cincinnati and Boonshoft visits we had almost no Ohio or Kentucky specimens in our database. Thanks to Boonshoft's Anthropology Curator Bill Kennedy (below, with Max) for helping us with access to the collections.Tomorrow "Mastodons of Unusual Size" continues with our next stop.

Fossil Friday - mastodon thoracic vertebra

As I'm in the middle of our Mastodons of Unusual Size data-collecting trip, my Fossil Friday post will have to be a short one. But, in keeping with our road trip topic, it will of course feature a mastodon!The specimen shown above is an anterior thoracic vertebra, shown in anterior view. The image is turned sideways to fit better on the screen, so the bottom of the vertebra is on the left. The bone is still in its field jacket, and has only been partially prepared.Thoracic vertebra in mammals are the ones that articulate with the ribs, and the articulations are visible on the ends of the processes projecting from each side of the vertebra. The tall neural spine extends from the top of the vertebra (right in the photo). The neural spines serve in part as muscle attachment points for muscles that hold up the head and help support the front legs. In quadrupedal animals with large, heavy heads, such as mastodons, the anterior neural spines are very long, providing more surface area and better leverage for those muscles.This vertebra was collected from the Diamond Valley Lake East Dam, close to where the Western Science Center is now located.

As I'm in the middle of our Mastodons of Unusual Size data-collecting trip, my Fossil Friday post will have to be a short one. But, in keeping with our road trip topic, it will of course feature a mastodon!The specimen shown above is an anterior thoracic vertebra, shown in anterior view. The image is turned sideways to fit better on the screen, so the bottom of the vertebra is on the left. The bone is still in its field jacket, and has only been partially prepared.Thoracic vertebra in mammals are the ones that articulate with the ribs, and the articulations are visible on the ends of the processes projecting from each side of the vertebra. The tall neural spine extends from the top of the vertebra (right in the photo). The neural spines serve in part as muscle attachment points for muscles that hold up the head and help support the front legs. In quadrupedal animals with large, heavy heads, such as mastodons, the anterior neural spines are very long, providing more surface area and better leverage for those muscles.This vertebra was collected from the Diamond Valley Lake East Dam, close to where the Western Science Center is now located.

Mastodons of Unusual Size - Cincinnati Museum of Natural History

After leaving Baton Rouge, Brett and I (accompanied by Max the Mastodon) headed north to our second data collection stop: the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History. The Overmyer mastodon from Indiana is one of the premier CMNH mastodons (Max is shown above with the lower jaw). This specimen has actually been published, so much of the data we needed was already available, but we were able to get measurements on postcranial bones and photos of the lower teeth.All told, we took measurements on 2 femora and 19 teeth, although 6 of the teeth have limited locality information. Several of the teeth were quite large, although none were as big as the monster tooth from Baton Rouge we saw on Tuesday. The lower jaw below was particularly interesting:

After leaving Baton Rouge, Brett and I (accompanied by Max the Mastodon) headed north to our second data collection stop: the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History. The Overmyer mastodon from Indiana is one of the premier CMNH mastodons (Max is shown above with the lower jaw). This specimen has actually been published, so much of the data we needed was already available, but we were able to get measurements on postcranial bones and photos of the lower teeth.All told, we took measurements on 2 femora and 19 teeth, although 6 of the teeth have limited locality information. Several of the teeth were quite large, although none were as big as the monster tooth from Baton Rouge we saw on Tuesday. The lower jaw below was particularly interesting: This specimen only has third molars, which are heavily worn across their entire length; the second molars have fallen out and the sockets have grown over. This was a really old animal when it died, very likely past 60 years old.The lower third molar below, from Kentucky, is also noteworthy for a couple of reasons:

This specimen only has third molars, which are heavily worn across their entire length; the second molars have fallen out and the sockets have grown over. This was a really old animal when it died, very likely past 60 years old.The lower third molar below, from Kentucky, is also noteworthy for a couple of reasons: First, it has five distinct lophs on the crown, instead of the four we usually see in Mammut third molars. Second, this is a remarkably narrow tooth; it's actually even narrow by California standards. So far we've only seen a handful of teeth with these proportions outside of California. That said, this is still a large tooth, much longer than any California tooth.After leaving Cincinnati we headed north to Richmond, Indiana, where we'll spend the next few days while visiting several area museums.

First, it has five distinct lophs on the crown, instead of the four we usually see in Mammut third molars. Second, this is a remarkably narrow tooth; it's actually even narrow by California standards. So far we've only seen a handful of teeth with these proportions outside of California. That said, this is still a large tooth, much longer than any California tooth.After leaving Cincinnati we headed north to Richmond, Indiana, where we'll spend the next few days while visiting several area museums.

Mastodons of Unusual Size - LSU

Today Brett and I made our first stop on our experiment.com - funded trip to collect data on mastodon tooth proportions: Louisiana State University.I received my Ph.D. from LSU in 1998, and this was only the second time I've been on campus since graduating. My graduate advisor, Dr. Judith Schiebout, is still at LSU, and Dr. Ting Suyin, who was a graduate student the same time I was there, is now LSU's vertebrate fossil collections manager:

Today Brett and I made our first stop on our experiment.com - funded trip to collect data on mastodon tooth proportions: Louisiana State University.I received my Ph.D. from LSU in 1998, and this was only the second time I've been on campus since graduating. My graduate advisor, Dr. Judith Schiebout, is still at LSU, and Dr. Ting Suyin, who was a graduate student the same time I was there, is now LSU's vertebrate fossil collections manager: Of course, our real reason for being here was to measure mastodons. We collected measurements and photographs for 17 teeth, although only 13 are suitable for the database (the others are too poorly preserved for a complete set of measurements).While the tooth proportions of the Louisiana specimens were about what we would expect for teeth from the Gulf Coast (relatively much wider than California specimens), I was struck by how large some of these teeth are. The tooth at the top, an upper 3rd molar from the Tunica Hills region, is a pretty large tooth that is both longer and wider than any California tooth. But even it was dwarfed by this monster from Baton Rouge:

Of course, our real reason for being here was to measure mastodons. We collected measurements and photographs for 17 teeth, although only 13 are suitable for the database (the others are too poorly preserved for a complete set of measurements).While the tooth proportions of the Louisiana specimens were about what we would expect for teeth from the Gulf Coast (relatively much wider than California specimens), I was struck by how large some of these teeth are. The tooth at the top, an upper 3rd molar from the Tunica Hills region, is a pretty large tooth that is both longer and wider than any California tooth. But even it was dwarfed by this monster from Baton Rouge:

These are occlusal views of the upper right 2nd molar and lower right 3rd molar; the 3rd molar is damaged, so we don't have the full width. These teeth are absolutely enormous. The 3rd molar is the second longest tooth in our database, and is more than 2.5 cm longer than any California m3. The M2 is 117.7 mm wide, the only M2 in our data set that's more than 100 mm wide!Below, Brett is holding a maxilla fragment with an M3 from another Louisiana specimen we measured today:

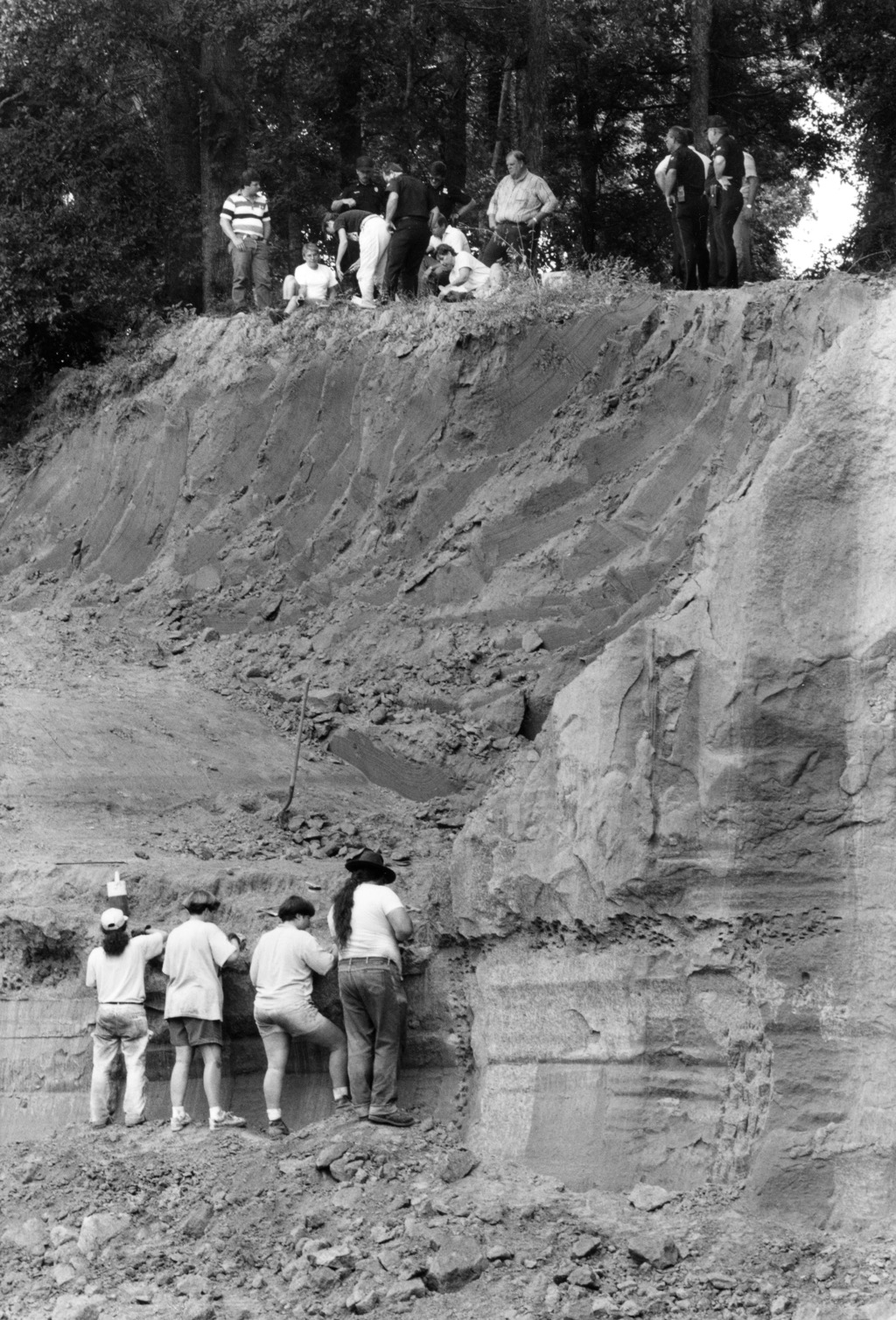

These are occlusal views of the upper right 2nd molar and lower right 3rd molar; the 3rd molar is damaged, so we don't have the full width. These teeth are absolutely enormous. The 3rd molar is the second longest tooth in our database, and is more than 2.5 cm longer than any California m3. The M2 is 117.7 mm wide, the only M2 in our data set that's more than 100 mm wide!Below, Brett is holding a maxilla fragment with an M3 from another Louisiana specimen we measured today: This specimen is special to me, because Brett and I led the excavation that recovered it. Brett and I were married in 1994, and after our honeymoon we drove to Baton Rouge where I was enrolled as a graduate student and Brett was starting a job as a lab technician for Dr. Schiebout. Immediately after we arrived we were called out to Angola, Louisiana to examine possible fossils that had been uncovered during a construction project at the Louisiana State Penitentiary. The remains turned out to be this specimen, and over the next several weeks Brett and I led an LSU crew on an excavation at the prison (this remains the only mastodon I've ever personally excavated, and the only time I've run an excavation inside a prison!). At the time we received a good deal of local media coverage, which only intensified when during the course of the excavation we discovered an unmarked and eroding 1800's-era cemetery directly above the excavation site. The photos below originally ran in the Baton Rouge Advocate, showing archaeologists working on the cemetery site at the top of the hill while we paleontologists simultaneously worked on the mastodon below them, and a closeup of the archaeological site:

This specimen is special to me, because Brett and I led the excavation that recovered it. Brett and I were married in 1994, and after our honeymoon we drove to Baton Rouge where I was enrolled as a graduate student and Brett was starting a job as a lab technician for Dr. Schiebout. Immediately after we arrived we were called out to Angola, Louisiana to examine possible fossils that had been uncovered during a construction project at the Louisiana State Penitentiary. The remains turned out to be this specimen, and over the next several weeks Brett and I led an LSU crew on an excavation at the prison (this remains the only mastodon I've ever personally excavated, and the only time I've run an excavation inside a prison!). At the time we received a good deal of local media coverage, which only intensified when during the course of the excavation we discovered an unmarked and eroding 1800's-era cemetery directly above the excavation site. The photos below originally ran in the Baton Rouge Advocate, showing archaeologists working on the cemetery site at the top of the hill while we paleontologists simultaneously worked on the mastodon below them, and a closeup of the archaeological site:

(That really is Brett and me, 22 years ago!)After documentation, the human remains were reburied in a new location. The mastodon remained in jackets until after I graduated, and was finally prepared sometime after 2000. Today was the first time Brett and I had seen the specimen since excavating it in 1994!Tomorrow we leave Baton Rouge and head north to visit more museums. Follow along here and on Max's Twitter feed (@MaxMastodon) and at #MastodonsOfUnusualSize.

(That really is Brett and me, 22 years ago!)After documentation, the human remains were reburied in a new location. The mastodon remained in jackets until after I graduated, and was finally prepared sometime after 2000. Today was the first time Brett and I had seen the specimen since excavating it in 1994!Tomorrow we leave Baton Rouge and head north to visit more museums. Follow along here and on Max's Twitter feed (@MaxMastodon) and at #MastodonsOfUnusualSize.

Fossil Friday - mastodon molar

Sometimes the fossils we recover are a little worse for wear. The remains may have deteriorated before burial, been damaged or deformed by sediment weight, structural forces, or groundwater after burial, weather out of the sediment and get eroded before discovery, or damaged during the act of discovery or excavation (I've collected numerous fossils that were "discovered" by bulldozers!). Sometimes it seems amazing that any fossils reach us at all. And yet, even these damaged specimens can be significant.The rather amorphous lump above is actually a mastodon tooth from Diamond Valley Lake, seen in occlusal view (the chewing surface). If you don't look at mastodon teeth on a regular basis, it might be a little difficult to recognize at first, because a lot of the enamel is missing. It's much more recognizable in lateral view, although the damage to the crown is still obvious: