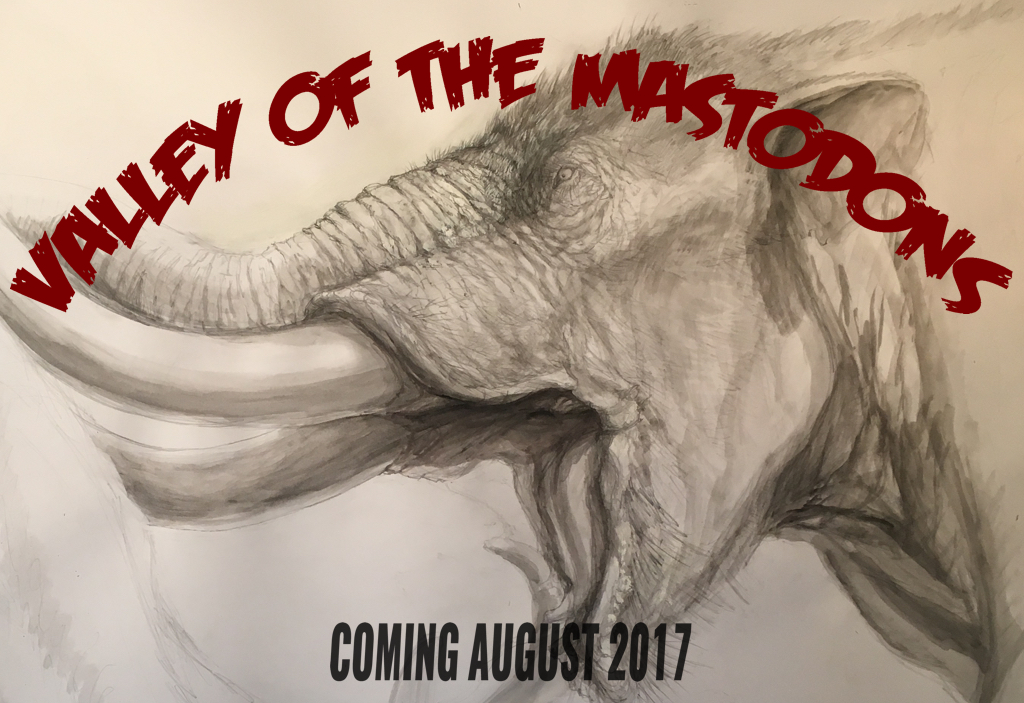

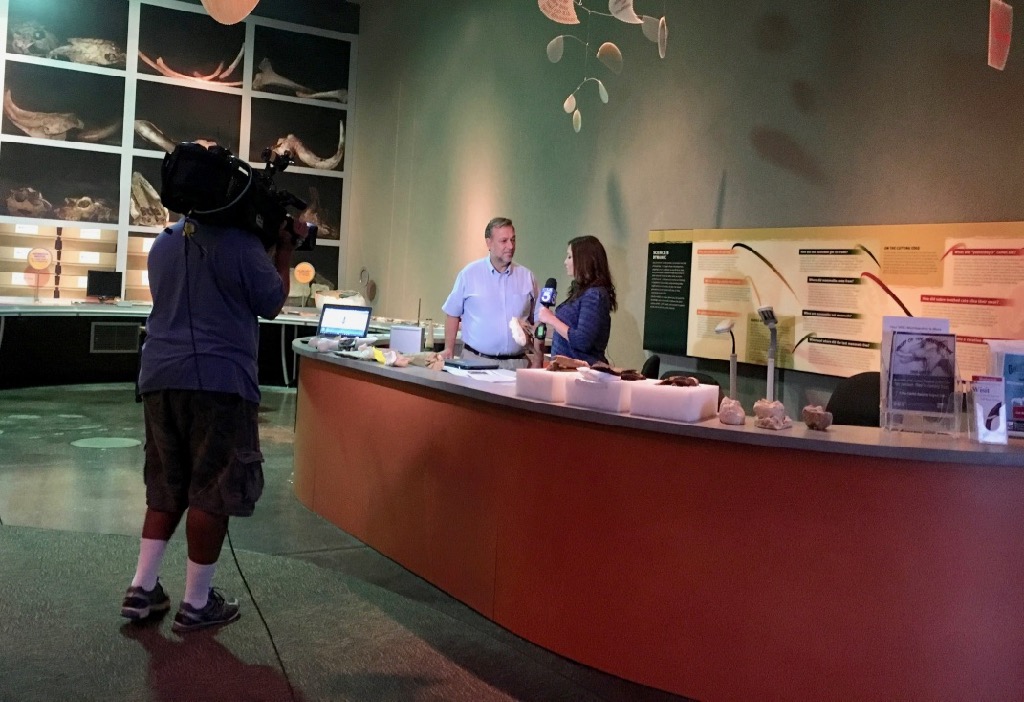

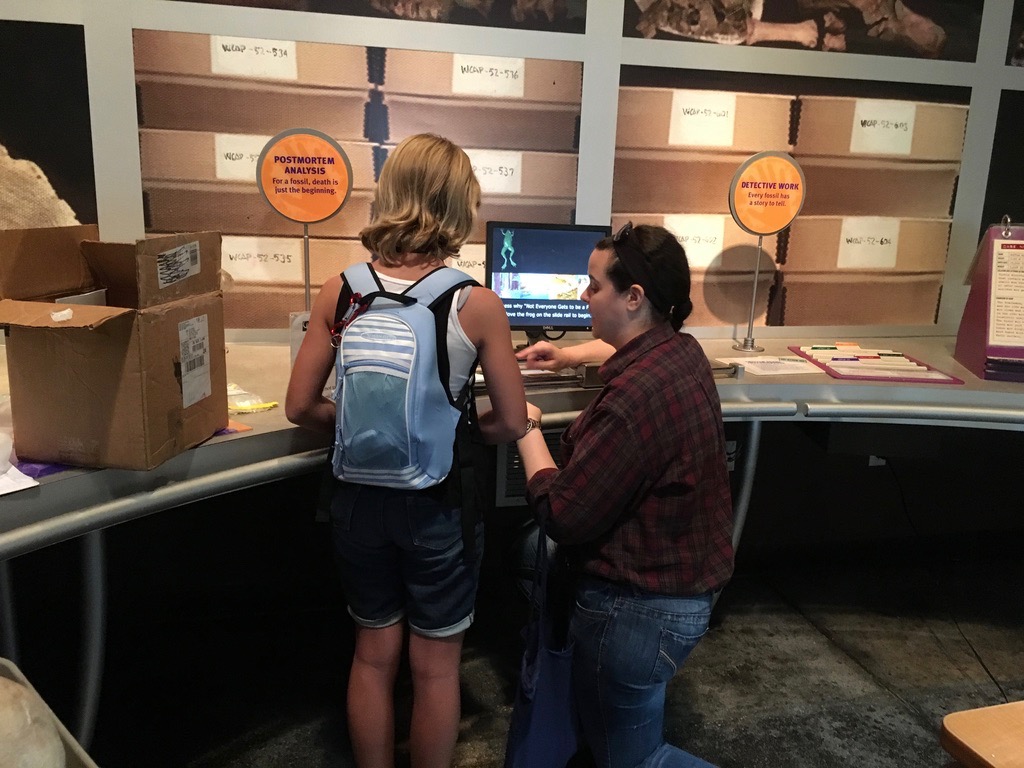

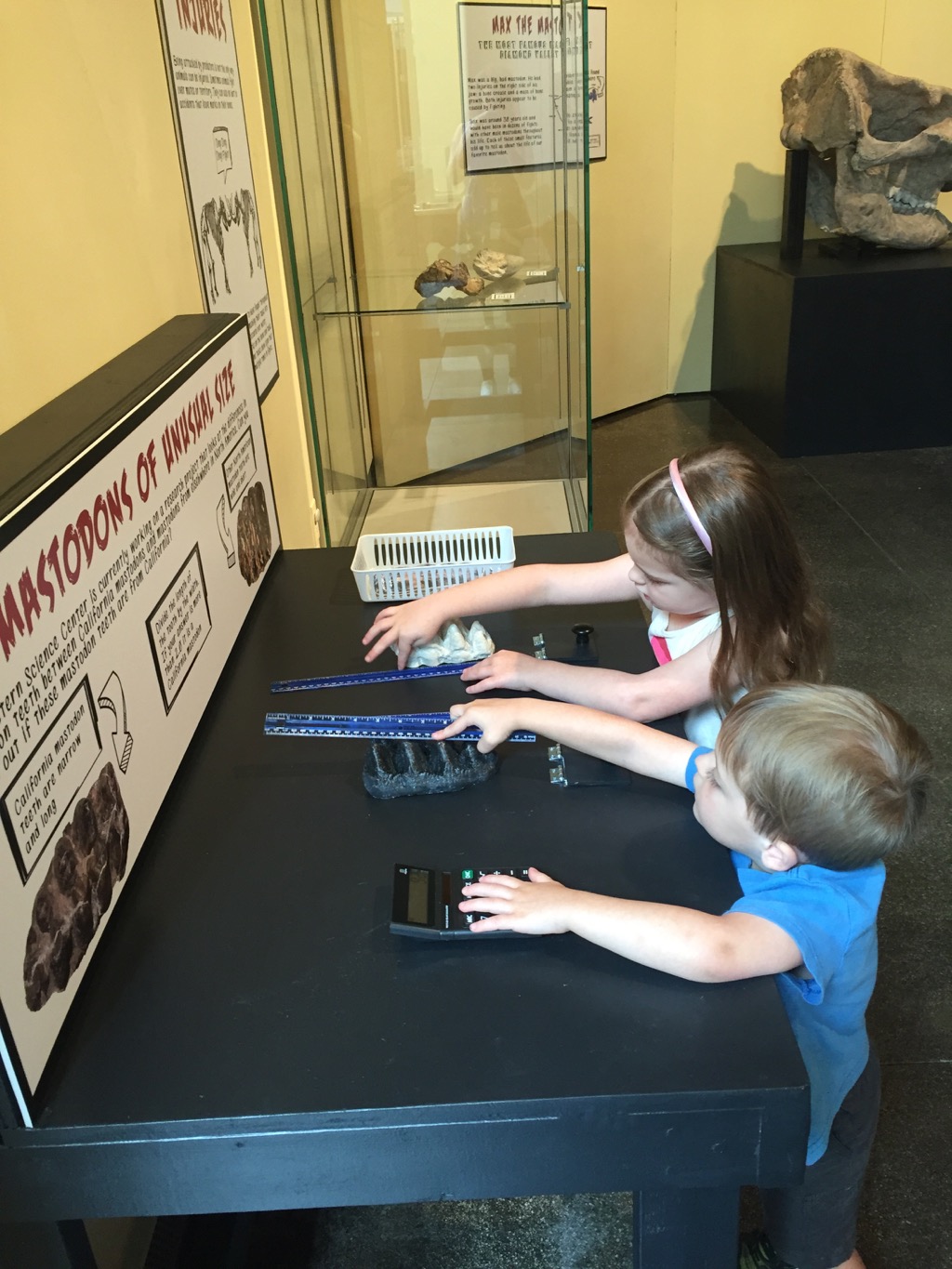

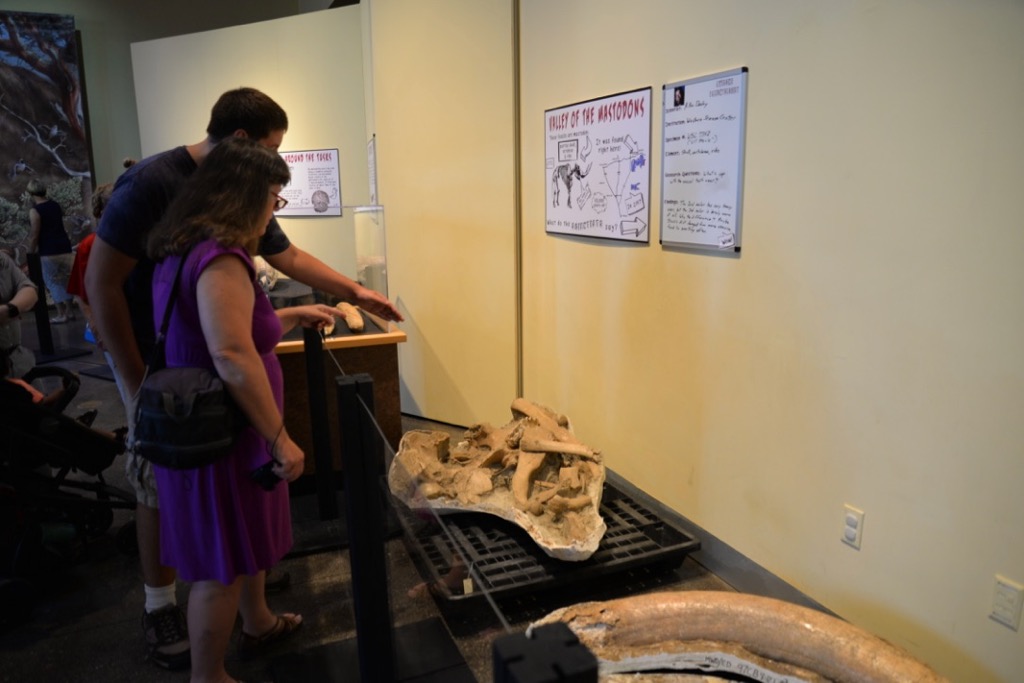

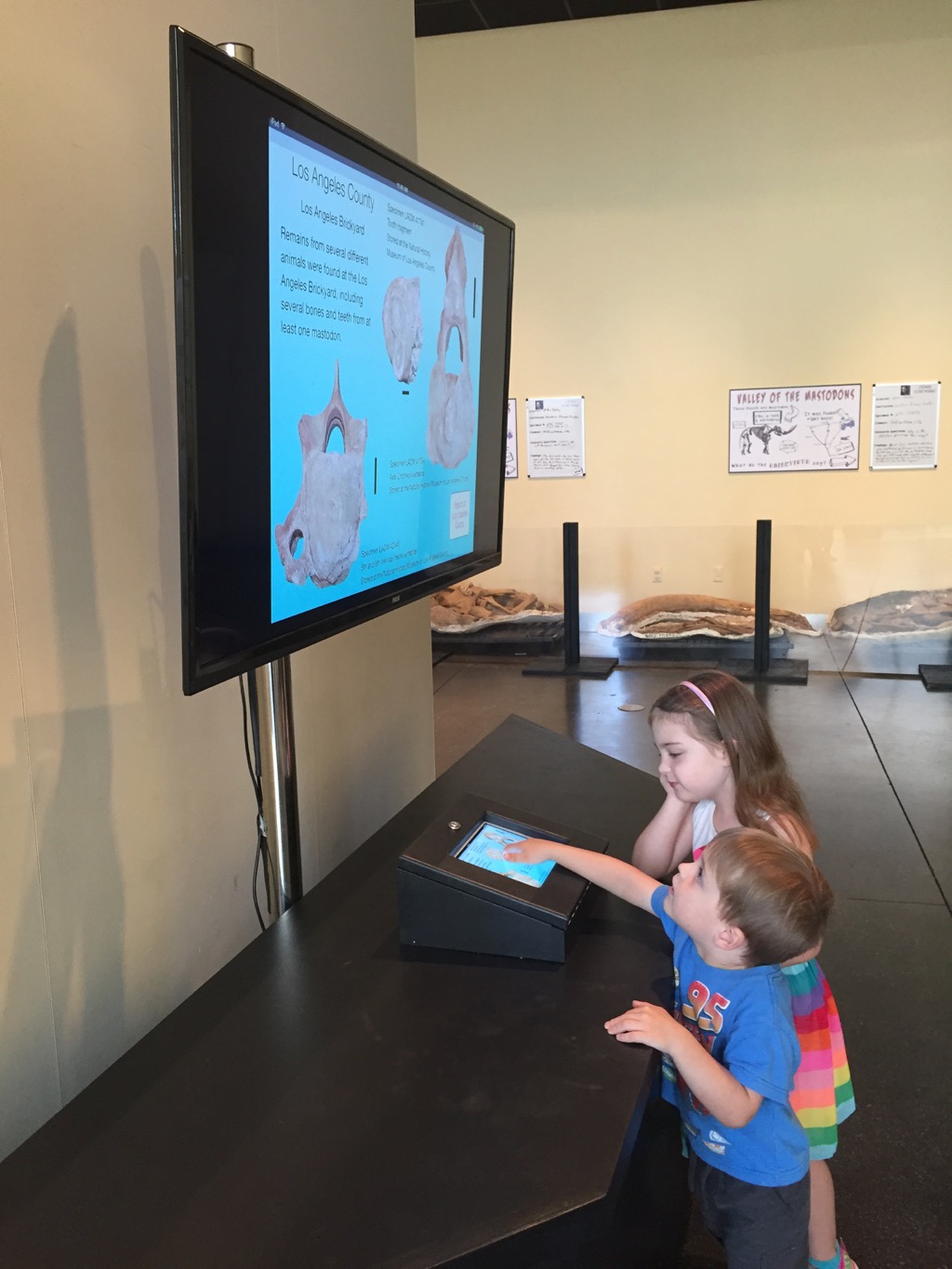

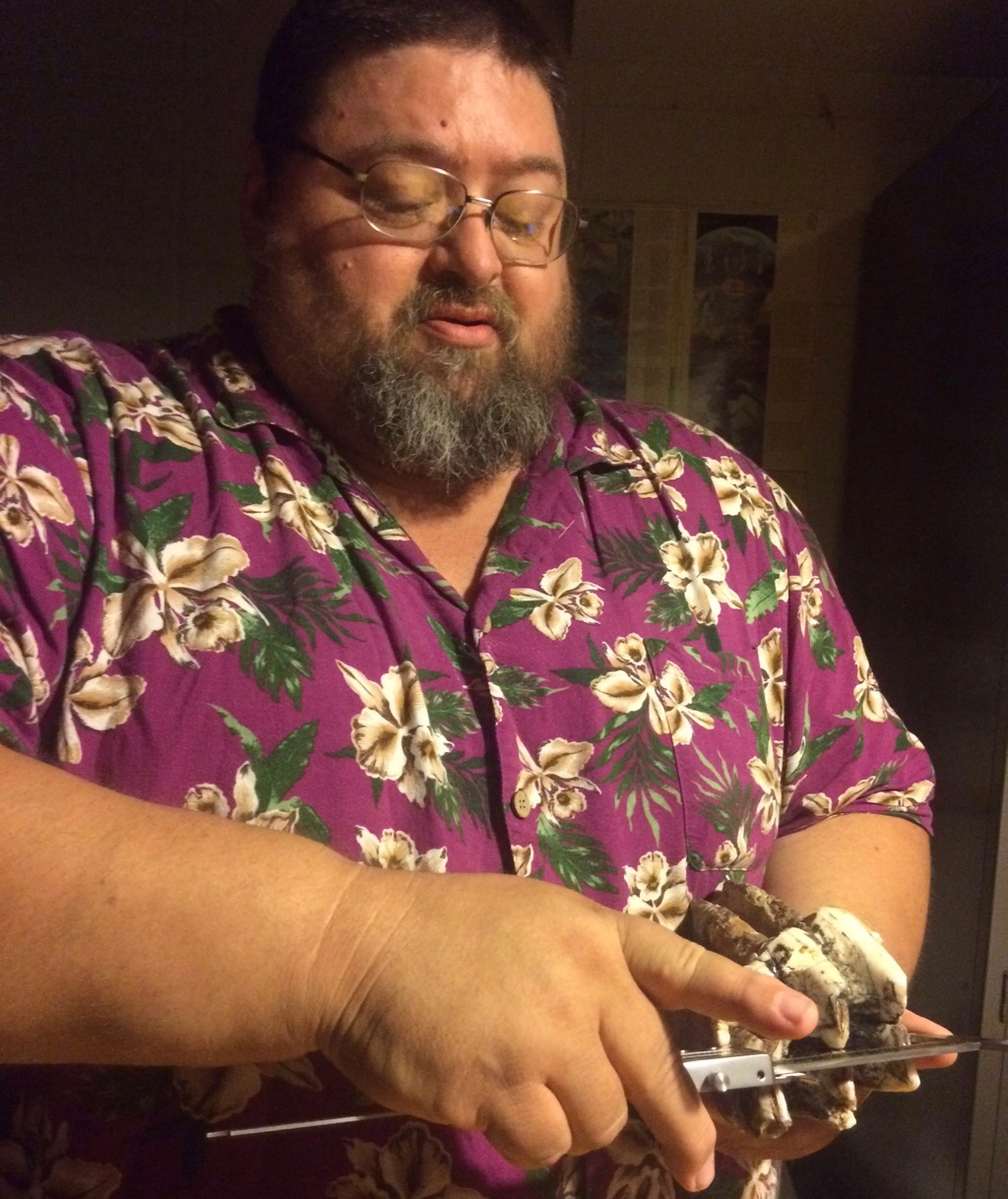

I missed doing a Fossil Friday post last week. But my reason was a good one: that was the opening day for our new exhibit, Valley of the Mastodons!Valley of the Mastodons was more than just an exhibit, however. It started with a 3-day symposium with 17 scientists and science communicators from the US and Canada examining the WSC mastodon collection, giving presentations, engaging with the public, and helping with the exhibit. Besides being what we believe to be the largest exhibit of mastodons in history, we're attempting to break new ground in making the act of research itself part of outreach, in real time.We had pretty good media exposure, with more to come:KTLA 5PLOS Paleo CommunityThe Press-EnterpriseSauropod Vertebra Picture of the WeekDontmesswithdinosaurs.comI'll have lots more to say about Valley of the Mastodons in the future, including at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Calgary later this month. But for now I want to thank our sponsors and supporters Golden Village Palms RV Resort, Abbott Vascular, Bone Clones, and Brian Engh Paleoart, as well as the participants that made this event such a success! Below are bunches of pictures from the event:

I missed doing a Fossil Friday post last week. But my reason was a good one: that was the opening day for our new exhibit, Valley of the Mastodons!Valley of the Mastodons was more than just an exhibit, however. It started with a 3-day symposium with 17 scientists and science communicators from the US and Canada examining the WSC mastodon collection, giving presentations, engaging with the public, and helping with the exhibit. Besides being what we believe to be the largest exhibit of mastodons in history, we're attempting to break new ground in making the act of research itself part of outreach, in real time.We had pretty good media exposure, with more to come:KTLA 5PLOS Paleo CommunityThe Press-EnterpriseSauropod Vertebra Picture of the WeekDontmesswithdinosaurs.comI'll have lots more to say about Valley of the Mastodons in the future, including at the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Calgary later this month. But for now I want to thank our sponsors and supporters Golden Village Palms RV Resort, Abbott Vascular, Bone Clones, and Brian Engh Paleoart, as well as the participants that made this event such a success! Below are bunches of pictures from the event:

Fossils of my youth

Inspired by the #GatewayFossil hashtag on Twitter, I'm reposting this piece that I originally published at "Updates from the Paleontology Lab" on June 9, 2009.My first exposure to fossils in the field (as opposed to in a museum) occurred when I was around 5 years old.When my father was a teenager he used to hunt with my grandfather in the mountains along the Botetourt-Craig County line in western Virginia, where he had casually noticed some fossils in the stream gravels (I’m not sure he knew at the time what they were). My mother has always had an interest in rocks and fossils (due to the influence of her grandfather), so my dad used to take us up to that area to look for fossils. We mostly found molds of crinoid column segments and occasional brachiopods in a brown sandstone (above). With the limited resources available to a relatively poor child growing up in the country at that time (no internet!), I didn’t know much more about those fossils, and doing my college work in Minnesota and Louisiana I never actually learned much about the rocks I collected in my youth, a point that was emphasized with the discovery last year of the Boxley stromatolite in Bedford County (where I grew up).Now that I’m back in Virginia with years of geologic training behind me I can look at these rocks in a new light. Last Friday, my father and I spent the day driving around Botetourt and Craig Counties, looking at rocks. Near Webster, VA we stopped at a railroad trestle close to the Blue Ridge Fault, with deformed Cambrian Rome Formation exposed in the trestle foundation:

Inspired by the #GatewayFossil hashtag on Twitter, I'm reposting this piece that I originally published at "Updates from the Paleontology Lab" on June 9, 2009.My first exposure to fossils in the field (as opposed to in a museum) occurred when I was around 5 years old.When my father was a teenager he used to hunt with my grandfather in the mountains along the Botetourt-Craig County line in western Virginia, where he had casually noticed some fossils in the stream gravels (I’m not sure he knew at the time what they were). My mother has always had an interest in rocks and fossils (due to the influence of her grandfather), so my dad used to take us up to that area to look for fossils. We mostly found molds of crinoid column segments and occasional brachiopods in a brown sandstone (above). With the limited resources available to a relatively poor child growing up in the country at that time (no internet!), I didn’t know much more about those fossils, and doing my college work in Minnesota and Louisiana I never actually learned much about the rocks I collected in my youth, a point that was emphasized with the discovery last year of the Boxley stromatolite in Bedford County (where I grew up).Now that I’m back in Virginia with years of geologic training behind me I can look at these rocks in a new light. Last Friday, my father and I spent the day driving around Botetourt and Craig Counties, looking at rocks. Near Webster, VA we stopped at a railroad trestle close to the Blue Ridge Fault, with deformed Cambrian Rome Formation exposed in the trestle foundation:

The concrete used to build the foundation also had large chunks of Conococheague Formation embedded in it (this bridge is only a couple of miles from the Boxley Blue Ridge Quarry):

The concrete used to build the foundation also had large chunks of Conococheague Formation embedded in it (this bridge is only a couple of miles from the Boxley Blue Ridge Quarry): Moving into Craig County, we followed Stone Coal Road into the mountains (although I’m using the term “road” in its broadest sense):

Moving into Craig County, we followed Stone Coal Road into the mountains (although I’m using the term “road” in its broadest sense): We came across several roadcuts of interbedded shales and fine-grained sandstones:

We came across several roadcuts of interbedded shales and fine-grained sandstones: These rocks are from the Devonian Chemung Formation (apparently redescribed as the Foreknobs Formation). They are tilted nearly 90 degrees, which is especially clear where the rocks intersect with the road (the lines leading toward the truck):

These rocks are from the Devonian Chemung Formation (apparently redescribed as the Foreknobs Formation). They are tilted nearly 90 degrees, which is especially clear where the rocks intersect with the road (the lines leading toward the truck): In a few places the Chemung was rippled:

In a few places the Chemung was rippled: And eventually we found some examples of the fossil crinoid and brachiopod molds that are common in this unit:

And eventually we found some examples of the fossil crinoid and brachiopod molds that are common in this unit: Returning to my father’s house in Botetourt County I took a look at the rocks exposed under his house and storage shed. The exposures are pretty limited:

Returning to my father’s house in Botetourt County I took a look at the rocks exposed under his house and storage shed. The exposures are pretty limited: Even so, there were some interesting bits, including this contact between a cross-bedded sandstone and a limestone:

Even so, there were some interesting bits, including this contact between a cross-bedded sandstone and a limestone: According to the Geologic Map of Virginia the mountain where Dad’s house is located includes both the Rome and Elbrook Formations (both Cambrian); I think this rock may expose the contact between them (with the Elbrook being the lighter-colored limestone at the top).

According to the Geologic Map of Virginia the mountain where Dad’s house is located includes both the Rome and Elbrook Formations (both Cambrian); I think this rock may expose the contact between them (with the Elbrook being the lighter-colored limestone at the top).

The role of museums

Inspired by Brian Switek’s recent article in Aeon, I was reminded of a post I wrote several years ago for “Updates from the Paleontology Lab” about different types of institutions that describe themselves with the term “museum”. What follows is an updated and edited version of that post.Over the course of my career I’ve had the opportunity to visit numerous natural history museums for a variety of reasons, as a researcher, a public lecturer, a tourist, and, of course, as an employee. The institutions are highly diverse in terms of their missions, and it’s instructive to reflect on those differences. The points I’m going to make are largely anecdotal, but should serve to give a general idea of the different types of natural history museums.During my time in Virginia, I made several visits to the Science Museum of Virginia (SMV), located in Richmond. SMV has a very large exhibit area and I was always impressed with the range and quality of hands-on interactives in their exhibits, but there were very few specimens on display.

Inspired by Brian Switek’s recent article in Aeon, I was reminded of a post I wrote several years ago for “Updates from the Paleontology Lab” about different types of institutions that describe themselves with the term “museum”. What follows is an updated and edited version of that post.Over the course of my career I’ve had the opportunity to visit numerous natural history museums for a variety of reasons, as a researcher, a public lecturer, a tourist, and, of course, as an employee. The institutions are highly diverse in terms of their missions, and it’s instructive to reflect on those differences. The points I’m going to make are largely anecdotal, but should serve to give a general idea of the different types of natural history museums.During my time in Virginia, I made several visits to the Science Museum of Virginia (SMV), located in Richmond. SMV has a very large exhibit area and I was always impressed with the range and quality of hands-on interactives in their exhibits, but there were very few specimens on display. Extinction exhibit at the Science Museum of Virginia.SMV is an excellent example of a science education center. These institutions generally have few (if any) collections, and usually what collections they have are used in education rather than research. They are generally staffed by educators, with few if any active research scientists. The primary audiences are families with school-age children or schools themselves, especially elementary and middle schools, and this is reflected in the types of exhibits that are selected. This is not to say that adults can’t benefit or enjoy these exhibits - just that they are not the primary audience.A number of colleges have campus museums; two that I’ve visited recently are the Joseph Moore Museum at Earlham College and the Museum of Earth Science at Radford University. While it used to be fairly common for small colleges to maintain museums, they fell into disfavor in recent decades; fortunately they may be experiencing a bit of a renaissance.

Extinction exhibit at the Science Museum of Virginia.SMV is an excellent example of a science education center. These institutions generally have few (if any) collections, and usually what collections they have are used in education rather than research. They are generally staffed by educators, with few if any active research scientists. The primary audiences are families with school-age children or schools themselves, especially elementary and middle schools, and this is reflected in the types of exhibits that are selected. This is not to say that adults can’t benefit or enjoy these exhibits - just that they are not the primary audience.A number of colleges have campus museums; two that I’ve visited recently are the Joseph Moore Museum at Earlham College and the Museum of Earth Science at Radford University. While it used to be fairly common for small colleges to maintain museums, they fell into disfavor in recent decades; fortunately they may be experiencing a bit of a renaissance. Allosaurus cast on display at the Joseph Moore Museum.Campus museums are almost as eclectic as the colleges that run them, but they do tend to have a few things in common. Collections at these museums are primarily for teaching (although there are exceptions; we’re including several Joseph Moore Museum specimens in the “Mastodons of Unusual Size” project). Most of these museum have few or no paid full-time staff, and often are run part-time by a faculty member. Most of the museums’ operational activities, including their programs, are conducted by students. Often these institutions serve as teaching museums, and are where many career museum professionals got their initial exposure to museum operations.

Allosaurus cast on display at the Joseph Moore Museum.Campus museums are almost as eclectic as the colleges that run them, but they do tend to have a few things in common. Collections at these museums are primarily for teaching (although there are exceptions; we’re including several Joseph Moore Museum specimens in the “Mastodons of Unusual Size” project). Most of these museum have few or no paid full-time staff, and often are run part-time by a faculty member. Most of the museums’ operational activities, including their programs, are conducted by students. Often these institutions serve as teaching museums, and are where many career museum professionals got their initial exposure to museum operations. Collecting mastodon data at the Joseph Moore Museum.Finally, there are research museums such as the Western Science Center. Many research museums are operated by federal, state, or local governments (I previously worked at the Virginia Museum of Natural History, a state-funded research museum). Some, such as the Florida Museum of Natural History, are departments within research universities, which are also often state government-supported. A few, such as the American Museum of Natural History and Western Science Center, are stand-alone non-profit institutions operated in most cases by private foundations. While research museums may have different origins and associations, they all share a common feature: a permanent collection of research specimens. The primary function of these museums is to preserve the specimens and associated data that form the basis of natural science. These museums will usually have a written collections policy that defines the scope of the collection, how specimens are acquired, and how they are made available for study. The collections supersede any particular staff member; the curators and collections staff are there primarily there to support and maintain the collections, not the other way around.

Collecting mastodon data at the Joseph Moore Museum.Finally, there are research museums such as the Western Science Center. Many research museums are operated by federal, state, or local governments (I previously worked at the Virginia Museum of Natural History, a state-funded research museum). Some, such as the Florida Museum of Natural History, are departments within research universities, which are also often state government-supported. A few, such as the American Museum of Natural History and Western Science Center, are stand-alone non-profit institutions operated in most cases by private foundations. While research museums may have different origins and associations, they all share a common feature: a permanent collection of research specimens. The primary function of these museums is to preserve the specimens and associated data that form the basis of natural science. These museums will usually have a written collections policy that defines the scope of the collection, how specimens are acquired, and how they are made available for study. The collections supersede any particular staff member; the curators and collections staff are there primarily there to support and maintain the collections, not the other way around.  Dr. Katy Smith working in the collections repository at the Western Science Center.Specimens in a research collection are selected for their scientific value. Many of these specimens may be visually appealing, but that’s not the reason they’re acquired. In fact, the majority of a research museum’s collections are rarely if ever viewed by anyone except specialists who incorporate the data from those specimens into their research. In this respect, research museums stand apart from science education centers and teaching museums.Of course, these are broad categories that tend to merge into one another. Many museums have a close relationship with colleges, even if they aren't actually operated by a college. Some science education centers have small but significant research collections (the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery is a science education center where we collected mastodon data). Nearly all museums put a lot of effort into public education, regardless of their primary focus. Nevertheless, I'd suggest that most natural history museums tend to fall closest to one of these three categories.With such a range of missions and holdings, why are all these disparate institutions called museums? There is one feature that they all tend to share: exhibits. Even though the primary function of a research museum is maintaining collections, exhibits are a critical supporting part of that mission. To extend an analogy that a friend once suggested to me, why does a football stadium or a theatre have seats? Why do we have art galleries? All the players, actors, or artists require is a field, stage, or easel. The seats in a stadium or theatre are for everyone else – those who aren’t athletes or actors. The theatre, art gallery, and playing field are venues for non-specialists to experience these activities. Likewise, museums are the stages that scientists use to present their work to others. The vast majority of scientific research is funded, in one way or another, by the public. We have an obligation to make the fruits of our scientific endeavors available to as many people as we can, and particularly to those who pay for them.With exhibits serving as one of the significant public faces of research, it’s easy for the public to become misled about the function of museums and exhibits, particularly when the term “museum” is used for a variety of institutions. It can seem to a visitor that the only reason museums exist is to have exhibits. In the case of a science education center such as SMV, this is actually the case; they are an institution that exists to provide science education, primarily through exhibits. But the knowledge that’s imparted in SMV’s exhibits came from somewhere; someone had to collect and interpret the raw data that led to those discoveries. That was done in university and government research facilities…and in research museums. Institutions such as WSC don’t just provide the scientific knowledge described in our own exhibits, but also for the exhibits in other venues that don’t perform research or maintain collections. For research museums, we don’t acquire collections in order to supply the exhibits; rather, the exhibits exist to teach the public about the significance of our collections. All these different types of museums may share exhibits as a common point, but they perform different, yet complimentary, roles in the advancement of science.

Dr. Katy Smith working in the collections repository at the Western Science Center.Specimens in a research collection are selected for their scientific value. Many of these specimens may be visually appealing, but that’s not the reason they’re acquired. In fact, the majority of a research museum’s collections are rarely if ever viewed by anyone except specialists who incorporate the data from those specimens into their research. In this respect, research museums stand apart from science education centers and teaching museums.Of course, these are broad categories that tend to merge into one another. Many museums have a close relationship with colleges, even if they aren't actually operated by a college. Some science education centers have small but significant research collections (the Boonshoft Museum of Discovery is a science education center where we collected mastodon data). Nearly all museums put a lot of effort into public education, regardless of their primary focus. Nevertheless, I'd suggest that most natural history museums tend to fall closest to one of these three categories.With such a range of missions and holdings, why are all these disparate institutions called museums? There is one feature that they all tend to share: exhibits. Even though the primary function of a research museum is maintaining collections, exhibits are a critical supporting part of that mission. To extend an analogy that a friend once suggested to me, why does a football stadium or a theatre have seats? Why do we have art galleries? All the players, actors, or artists require is a field, stage, or easel. The seats in a stadium or theatre are for everyone else – those who aren’t athletes or actors. The theatre, art gallery, and playing field are venues for non-specialists to experience these activities. Likewise, museums are the stages that scientists use to present their work to others. The vast majority of scientific research is funded, in one way or another, by the public. We have an obligation to make the fruits of our scientific endeavors available to as many people as we can, and particularly to those who pay for them.With exhibits serving as one of the significant public faces of research, it’s easy for the public to become misled about the function of museums and exhibits, particularly when the term “museum” is used for a variety of institutions. It can seem to a visitor that the only reason museums exist is to have exhibits. In the case of a science education center such as SMV, this is actually the case; they are an institution that exists to provide science education, primarily through exhibits. But the knowledge that’s imparted in SMV’s exhibits came from somewhere; someone had to collect and interpret the raw data that led to those discoveries. That was done in university and government research facilities…and in research museums. Institutions such as WSC don’t just provide the scientific knowledge described in our own exhibits, but also for the exhibits in other venues that don’t perform research or maintain collections. For research museums, we don’t acquire collections in order to supply the exhibits; rather, the exhibits exist to teach the public about the significance of our collections. All these different types of museums may share exhibits as a common point, but they perform different, yet complimentary, roles in the advancement of science.

Fossil Friday - Stories from Bones exhibit

For Fossil Friday this week, I want to highlight Western Science Center's new exhibit "Stories from Bones", which opens tomorrow.While WSC has excellent paleontology exhibits, as with any museum with a large collection many of the specimens are not on public display. There are a variety of reasons for this. Of course, the biggest obstacle is money; cases, information panels, interactive, floor space, and other requirements for an effective display are all expensive, and even the healthiest museums operate on a shoestring budget. Besides money issues, many specimens are just not suitable for display. Perhaps they're too fragile to risk moving around too much, or too fragmentary to interpret for the public (a specimen that visually looks like a piece of junk can still produce valuable scientific data). Even with all these limitations, we strive to make as much of our collections accessible to the public as possible. "Stories from Bones" is a result of that effort.

For Fossil Friday this week, I want to highlight Western Science Center's new exhibit "Stories from Bones", which opens tomorrow.While WSC has excellent paleontology exhibits, as with any museum with a large collection many of the specimens are not on public display. There are a variety of reasons for this. Of course, the biggest obstacle is money; cases, information panels, interactive, floor space, and other requirements for an effective display are all expensive, and even the healthiest museums operate on a shoestring budget. Besides money issues, many specimens are just not suitable for display. Perhaps they're too fragile to risk moving around too much, or too fragmentary to interpret for the public (a specimen that visually looks like a piece of junk can still produce valuable scientific data). Even with all these limitations, we strive to make as much of our collections accessible to the public as possible. "Stories from Bones" is a result of that effort.

Mammoth jaw display in "Stories from Bones".

Mammoth jaw display in "Stories from Bones".

An important aspect of planning an effective exhibit is developing a theme. An exhibit is telling a story, and you need to be aware of what that story is as the exhibit is being designed. The theme might be "We have a bunch of stuff!", but while that was a common theme in museums a century ago (and one I personally appreciate), it does not generally make for the most informative exhibit experience for the majority of visitors.Once the theme is established, it's important to stick to it, so that the exhibit story remains coherent. Imagine reading a mystery novel in which three chapters are devoted to a history of the development of the gunpowder used in the crime, and an additional chapter describes the etymology of the last name of the victim, when neither is important to the outcome of the story. Each of these things might be individually interesting, but if you try to talk about all of them then you risk obscuring everything. There is a real risk of this "mission creep" in an exhibit based on a data-rich field such as paleontology. We might talk about evolutionary relationships, paleoenvironmental indicators, biogeographic information, site-specific descriptions, or an array of other things. Talking about any of these might be a good idea; talking about all of them is a bad idea.The permanent paleontology exhibit at WSC does this very well. The exhibit is basically a review of the Diamond Valley Lake Local Fauna; what was here, how does it compare to the rest of Southern California, and (as a secondary point) what does it tell us about the local Pleistocene paleoenvironment. In contrast, "Stories from Bones" asks "What do these fossils tell us about the lives and deaths of these individual animals?".To that end, "Stories" has a series of displays that talk about how paleontologists determine how old an animal was when it died. We have several cases that look at tooth replacement in proboscideans, horses, and bison, such as the two mammoth jaws above (they're close to the same size, but one animal was about 30 years older than the other), or the three bison dentaries shown below that represent young, middle-aged, and elderly animals.

Bison jaw display in "Stories from Bones".

Bison jaw display in "Stories from Bones".

We have several examples of bones that were broken and healed, evidence of events that took place during an animal's life:

Broken and healed bones in "Stories from Bones".

Broken and healed bones in "Stories from Bones".

We also have several cases that describe taphonomic features, looking at what happened to an animal at or immediately after death.We designed and built a number of interactive displays for this exhibit. The most prominent is a cast and video of the CT scans of Max the Mastodon's lower jaw, taken back in August.

Max's CT-scan station in "Stories from Bones" during installation, under the watchful eye of @MaxMastodon.

Max's CT-scan station in "Stories from Bones" during installation, under the watchful eye of @MaxMastodon.

We're proud of the fact that several of our interactive displays ask visitors to map or measure specimens and reach conclusions based on their data:

A more extensive version of the bison tooth display shown here is also available as a guided activity for school groups visiting the museum, and as a kit available for purchase.If you're a regular reader of this blog, you'll find that "Stories from Bones" draws heavily from my past "Fossil Friday" posts. For most of those specimens, this is the first time they've ever been on public display, so if you're near Southern California make sure to stop by the museum. "Stories from Bones" opens on October 31, and will remain open into May 2016.

A more extensive version of the bison tooth display shown here is also available as a guided activity for school groups visiting the museum, and as a kit available for purchase.If you're a regular reader of this blog, you'll find that "Stories from Bones" draws heavily from my past "Fossil Friday" posts. For most of those specimens, this is the first time they've ever been on public display, so if you're near Southern California make sure to stop by the museum. "Stories from Bones" opens on October 31, and will remain open into May 2016.

SE GSA meeting Day 2

I'm on my way back home from the SE GSA conference, and I finally have a chance to write about the second day of the meeting. Things got very busy at the WSC booth (we sold most of our inventory of casts!), and as a result I missed the entire morning session of talks except for single poster.That poster was by Nickacia Young and Rowan Lockwood on the effects of cementation on the preservation of fossil shells in Late Miocene deposits on the Virginia Coastal Plain. These deposits, called the Eastover Formation, are extremely rich in fossil shells. They are usually unlithified, meaning that the sediments are soft and can be dug out with a pick and shovel, such as in the image above. But in a few places the Eastover is lithified, meaning that it has fused into solid rock, as with the orange blocks in the image below:

I'm on my way back home from the SE GSA conference, and I finally have a chance to write about the second day of the meeting. Things got very busy at the WSC booth (we sold most of our inventory of casts!), and as a result I missed the entire morning session of talks except for single poster.That poster was by Nickacia Young and Rowan Lockwood on the effects of cementation on the preservation of fossil shells in Late Miocene deposits on the Virginia Coastal Plain. These deposits, called the Eastover Formation, are extremely rich in fossil shells. They are usually unlithified, meaning that the sediments are soft and can be dug out with a pick and shovel, such as in the image above. But in a few places the Eastover is lithified, meaning that it has fused into solid rock, as with the orange blocks in the image below: According to Young and Lockwood the number of species of shells (the diversity) in the lithified Eastover is much lower than in unlithified samples. This could have implications in estimating biodiversity in other deposits in which the entire deposit is lithified; if it behaves like the Eastover we may only be seeing a small subset of the species that were originally present.In the afternoon I pick up a couple of talks in a session on faults and shear zones in the Appalachians. John Hickman discussed deeply buried fault zones beneath Kentucky, and suggested that they form part of a Precambrian rift system associated with the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia in the Late Proterozoic Eon.The next talk was presented by Chuck Bailey, on which I was one of four coauthors. This was on the presence of Mesozoic faults in the Hylas Fault Zone at the edge of the Virginia Coastal Plain and their effect on younger Cenozoic sediments. I was involved in this talk because one of the study sites was the Carmel Church Quarry, a marine fossil site that I have been excavating for more than 20 years. During and excavation I led at Carmel Church in 2014 we discovered a boulder field buried in the Miocene sediments along with whales and other marine fossils:

According to Young and Lockwood the number of species of shells (the diversity) in the lithified Eastover is much lower than in unlithified samples. This could have implications in estimating biodiversity in other deposits in which the entire deposit is lithified; if it behaves like the Eastover we may only be seeing a small subset of the species that were originally present.In the afternoon I pick up a couple of talks in a session on faults and shear zones in the Appalachians. John Hickman discussed deeply buried fault zones beneath Kentucky, and suggested that they form part of a Precambrian rift system associated with the breakup of the supercontinent Rodinia in the Late Proterozoic Eon.The next talk was presented by Chuck Bailey, on which I was one of four coauthors. This was on the presence of Mesozoic faults in the Hylas Fault Zone at the edge of the Virginia Coastal Plain and their effect on younger Cenozoic sediments. I was involved in this talk because one of the study sites was the Carmel Church Quarry, a marine fossil site that I have been excavating for more than 20 years. During and excavation I led at Carmel Church in 2014 we discovered a boulder field buried in the Miocene sediments along with whales and other marine fossils: I suspected that structural activity might be responsible for the presence of these boulders, and since Chuck was working on faults in this region I asked him to take a look at the boulder field. Based on work by Chuck and his students it appears that the boulder field was most likely formed by the reactivation of a Triassic fault in the Miocene.As soon as Chuck's talk was finished I raced to another lecture hall to catch the end of a session on teaching evolution in the southeast, organized by Patricia Kelley and Christy Visaggi. This was actually an all-day session with 16 talks, and while the booth kept me away from the morning session Brett was able to attend. I had to attend the afternoon session, though, because Brett and I were jointly presenting a talk on teaching activities for getting students used to making hypotheses based on limited data. This included a description of the cast-based teaching kits that Brett and I have been developing based on specimens housed at the Western Science Center, as well as the adaptation of online lessons for courses in historical sciences.The last talks at SE GSA were Friday afternoon. There were also several post-meeting field trips on Saturday, but with long drives ahead of us Brett and I had to start heading back to Virginia and California, respectively. This was a fun and productive meeting, and I have to say that, having attended conferences in dozens of cities, Chattanooga was one of the nicest conference cities I've ever seen.

I suspected that structural activity might be responsible for the presence of these boulders, and since Chuck was working on faults in this region I asked him to take a look at the boulder field. Based on work by Chuck and his students it appears that the boulder field was most likely formed by the reactivation of a Triassic fault in the Miocene.As soon as Chuck's talk was finished I raced to another lecture hall to catch the end of a session on teaching evolution in the southeast, organized by Patricia Kelley and Christy Visaggi. This was actually an all-day session with 16 talks, and while the booth kept me away from the morning session Brett was able to attend. I had to attend the afternoon session, though, because Brett and I were jointly presenting a talk on teaching activities for getting students used to making hypotheses based on limited data. This included a description of the cast-based teaching kits that Brett and I have been developing based on specimens housed at the Western Science Center, as well as the adaptation of online lessons for courses in historical sciences.The last talks at SE GSA were Friday afternoon. There were also several post-meeting field trips on Saturday, but with long drives ahead of us Brett and I had to start heading back to Virginia and California, respectively. This was a fun and productive meeting, and I have to say that, having attended conferences in dozens of cities, Chattanooga was one of the nicest conference cities I've ever seen.

WSC's Fossil Preparation Exhibit

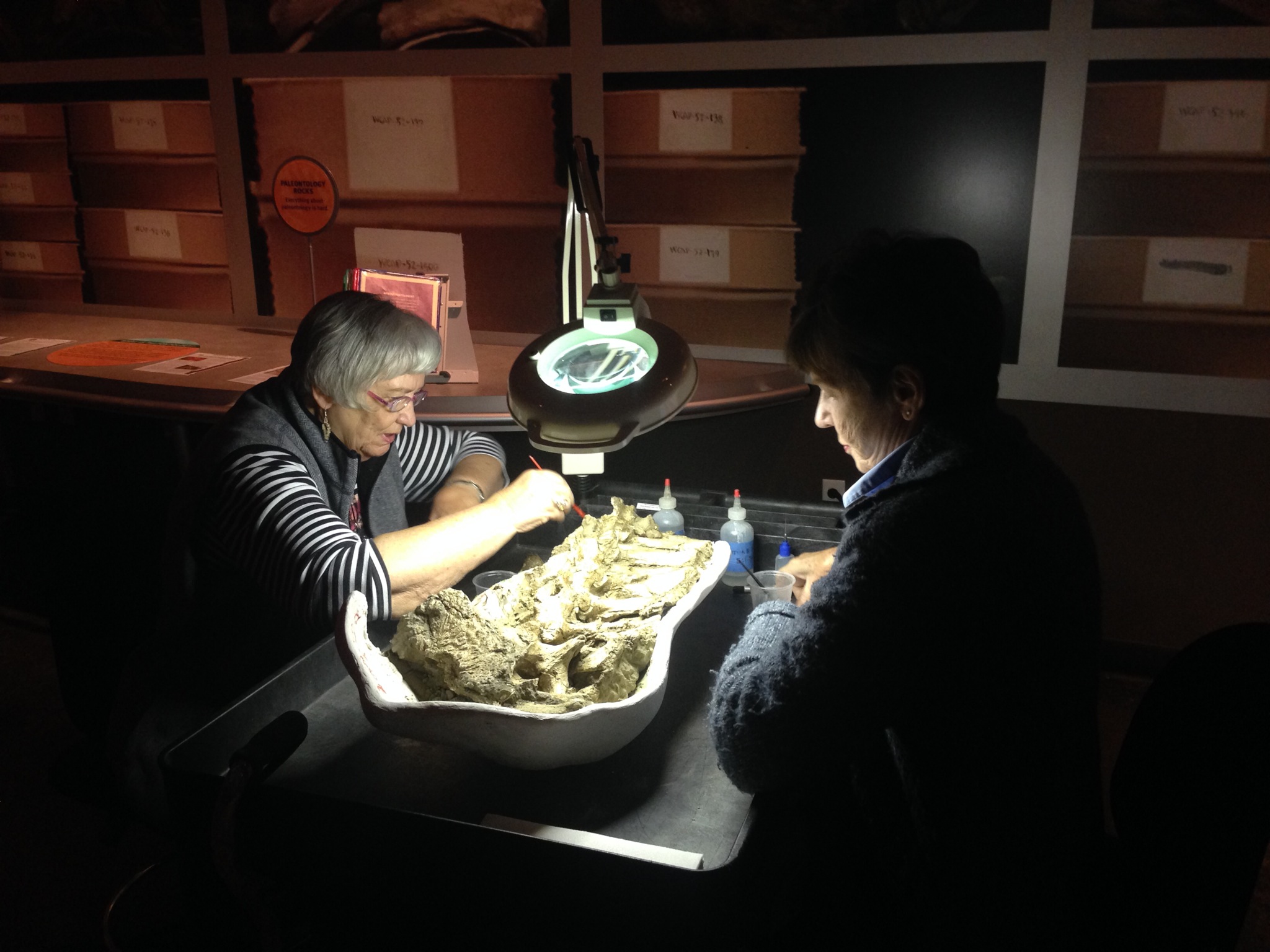

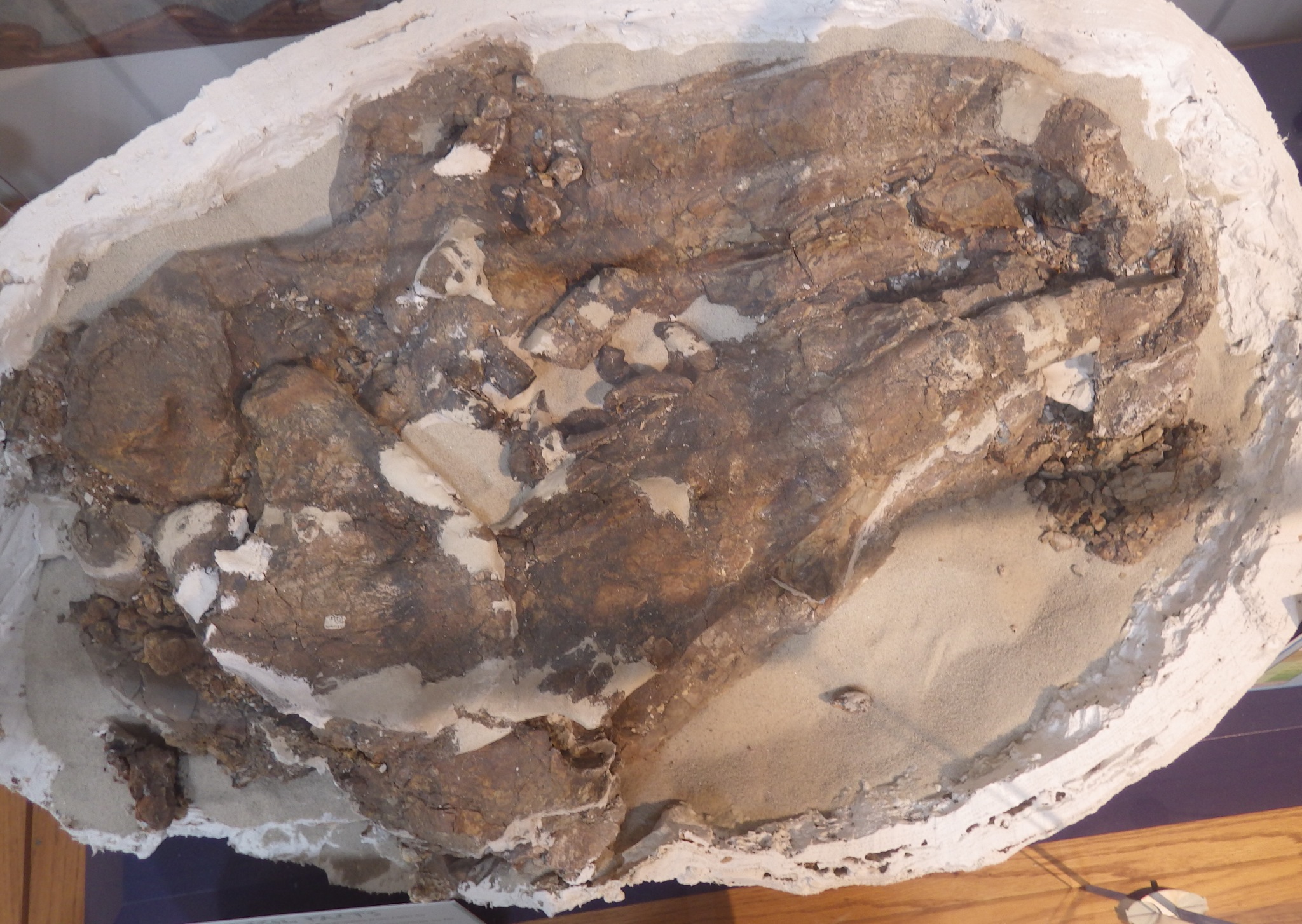

Like most collections-based museums, the Western Science Center has far more specimens than we could ever put on exhibit. We want to make our collections and procedures accessible to as many people as we can, but there are all kinds of technical, financial, and security hurdles. Even so, we're always exploring new ways to accomplish this, and today we're launching our latest effort — a fossil preparation demonstration area on the exhibit floor.Many natural history museums now have "fish-bowl"-style preparation labs so that visitors can observe staff and volunteers cleaning specimens. We hope to open such a lab one day at WSC, but that will take a lot of time and money and I'm not willing to wait. So we've put together a rolling preparation cart that our lab volunteers can take to the exhibit floor to do their work while answering questions and giving visitors an up-close look at the fossils.Two of our lab volunteers, Phyllis and Margit, have agreed to help us test out this new system by doing their prep work on the exhibit floor. Their initial specimen is an articulated series of seven Bison vertebrae that were partially prepared but are still in their field jacket.

Like most collections-based museums, the Western Science Center has far more specimens than we could ever put on exhibit. We want to make our collections and procedures accessible to as many people as we can, but there are all kinds of technical, financial, and security hurdles. Even so, we're always exploring new ways to accomplish this, and today we're launching our latest effort — a fossil preparation demonstration area on the exhibit floor.Many natural history museums now have "fish-bowl"-style preparation labs so that visitors can observe staff and volunteers cleaning specimens. We hope to open such a lab one day at WSC, but that will take a lot of time and money and I'm not willing to wait. So we've put together a rolling preparation cart that our lab volunteers can take to the exhibit floor to do their work while answering questions and giving visitors an up-close look at the fossils.Two of our lab volunteers, Phyllis and Margit, have agreed to help us test out this new system by doing their prep work on the exhibit floor. Their initial specimen is an articulated series of seven Bison vertebrae that were partially prepared but are still in their field jacket.

We're going to be testing and refining this system over the next few months. The preparation cart will be on the exhibit floor whenever we have staff or volunteers available to do preparation work, initially on Tuesdays from 10:00-12:00 but with additional hours to be added later.

We're going to be testing and refining this system over the next few months. The preparation cart will be on the exhibit floor whenever we have staff or volunteers available to do preparation work, initially on Tuesdays from 10:00-12:00 but with additional hours to be added later.

Prehistoric OC

I spent several hours yesterday at Prehistoric OC, a science festival organized by The Cooper Center and held at Ralph B. Clark Regional Park in Buena Park. Over 25 different information booths and attractions were available for visitors, as well as lectures throughout the day.

I spent several hours yesterday at Prehistoric OC, a science festival organized by The Cooper Center and held at Ralph B. Clark Regional Park in Buena Park. Over 25 different information booths and attractions were available for visitors, as well as lectures throughout the day.

There is also a small museum at the park that focuses on fossils from Orange County, many of which we're found in the park itself. Among the specimens on display are a large, essentially complete baleen whale. Below is part of the ventral side of the cranium and the lower jaw:

There is also a small museum at the park that focuses on fossils from Orange County, many of which we're found in the park itself. Among the specimens on display are a large, essentially complete baleen whale. Below is part of the ventral side of the cranium and the lower jaw:

One of the more unusual specimens is a skull of Paleoparadoxia, a member of the enigmatic marine mammal order Desmostylia:

One of the more unusual specimens is a skull of Paleoparadoxia, a member of the enigmatic marine mammal order Desmostylia:

There were also plenty of land mammals, including this partial bison skeleton:

There were also plenty of land mammals, including this partial bison skeleton:

Thanks to The Cooper Center for putting on such a fun and educational event!

Thanks to The Cooper Center for putting on such a fun and educational event!

Repost – The making of a scientist

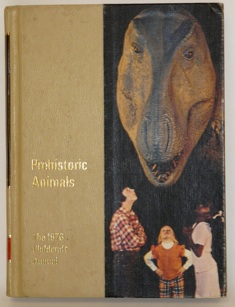

This morning Anthony Martin published a beautiful tribute at his blog Life Traces of the Georgia Coast, describing the importance of parental support and maximizing childhood opportunities in becoming a scientist, especially when growing up poor. Seemingly small acts of kindness and support can have dramatic and lasting effects. Reading his post, I was inspired to republish a post from my old blog, Updates from the Paleontology Lab. This was originally published in March 2011, on my 42nd birthday.I turned 42 years old today. According to Douglas Adams in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, 42 is the answer to life, the universe, and everything – clearly an opportunity for self reflection if there ever was one. And since 42 is, after all, the answer to a question, it seems appropriate to address a question that I’m frequently asked by museum visitors (especially parents with young children) – why did I become a scientist?A full answer to that question would require much more than a blog post. (In fact, it would probably need a book, written by psychiatrists). But there are factors that are easily examined, including the information I was exposed to as a child.As I look at the breadth of resources available today online, it’s jarring when I consider how far information technology has come in my lifetime, and I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that the personal computer and the internet are the most significant human inventions since the printing press.I grew up poor in rural Virginia. The nearest natural history museum was the Smithsonian, 200 miles away; by the time I started high school I had managed to visit there twice. We lived too far from the city to get good PBS reception, although I did get to watch it when we visited my grandmother in Roanoke. So initially I depended on libraries for information. Even this was a challenge; Stewartsville Elementary School was 15 miles away, and the nearest public library was 30 miles away in Vinton, so I couldn’t exactly walk there whenever I wanted. But I found enough science-themed books to apparently influence me for life, and by the 1st or 2nd grade I knew I wanted to be a scientist. Three books in particular that I read around that time (1976-78) were very influential:Childcraft Worldbook 1976 Annual – Prehistoric AnimalsMy grandmother had a complete Worldbook Encyclopedia set, as well as the Childcraft “How and Why” Library. Included with that was a subscription to the Childcraft Annuals, which were on a different topic each year. In 1976, the topic was Prehistoric Animals.The Prehistoric Animals issue was wonderful. It went through all kinds of amazing creatures, including eurypterids, trilobites, and crinoids like the ones I collected as a child in the mountains of Botetourt and Craig Counties. I was introduced to the Geologic Time Scale for the first time. There were dramatic paintings that I would stare at for hours, and later attempt to copy; Dunkleosteus, Dimetrodon, all kinds of dinosaurs and mammals. Over the next few years I probably read the book cover to cover at least a dozen times.

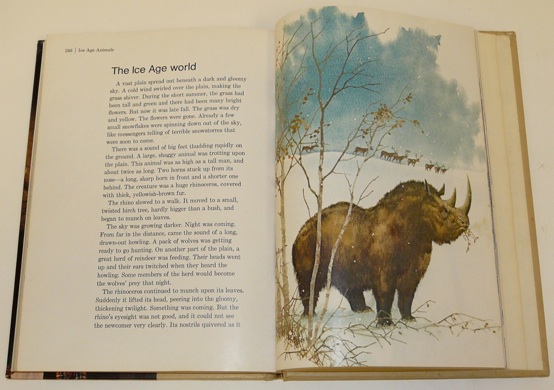

This morning Anthony Martin published a beautiful tribute at his blog Life Traces of the Georgia Coast, describing the importance of parental support and maximizing childhood opportunities in becoming a scientist, especially when growing up poor. Seemingly small acts of kindness and support can have dramatic and lasting effects. Reading his post, I was inspired to republish a post from my old blog, Updates from the Paleontology Lab. This was originally published in March 2011, on my 42nd birthday.I turned 42 years old today. According to Douglas Adams in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, 42 is the answer to life, the universe, and everything – clearly an opportunity for self reflection if there ever was one. And since 42 is, after all, the answer to a question, it seems appropriate to address a question that I’m frequently asked by museum visitors (especially parents with young children) – why did I become a scientist?A full answer to that question would require much more than a blog post. (In fact, it would probably need a book, written by psychiatrists). But there are factors that are easily examined, including the information I was exposed to as a child.As I look at the breadth of resources available today online, it’s jarring when I consider how far information technology has come in my lifetime, and I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that the personal computer and the internet are the most significant human inventions since the printing press.I grew up poor in rural Virginia. The nearest natural history museum was the Smithsonian, 200 miles away; by the time I started high school I had managed to visit there twice. We lived too far from the city to get good PBS reception, although I did get to watch it when we visited my grandmother in Roanoke. So initially I depended on libraries for information. Even this was a challenge; Stewartsville Elementary School was 15 miles away, and the nearest public library was 30 miles away in Vinton, so I couldn’t exactly walk there whenever I wanted. But I found enough science-themed books to apparently influence me for life, and by the 1st or 2nd grade I knew I wanted to be a scientist. Three books in particular that I read around that time (1976-78) were very influential:Childcraft Worldbook 1976 Annual – Prehistoric AnimalsMy grandmother had a complete Worldbook Encyclopedia set, as well as the Childcraft “How and Why” Library. Included with that was a subscription to the Childcraft Annuals, which were on a different topic each year. In 1976, the topic was Prehistoric Animals.The Prehistoric Animals issue was wonderful. It went through all kinds of amazing creatures, including eurypterids, trilobites, and crinoids like the ones I collected as a child in the mountains of Botetourt and Craig Counties. I was introduced to the Geologic Time Scale for the first time. There were dramatic paintings that I would stare at for hours, and later attempt to copy; Dunkleosteus, Dimetrodon, all kinds of dinosaurs and mammals. Over the next few years I probably read the book cover to cover at least a dozen times. Danny Dunn and the Fossil Cave, by Raymond Abrashkin and Jay Williams

Danny Dunn and the Fossil Cave, by Raymond Abrashkin and Jay Williams The Danny Dunn books were a series of science-themed children’s novels in which three children (Danny Dunn, Irene Miller, and Joe Pearson) became involved in various science and technology adventures. Danny’s mother was a live-in housekeeper for Professor Bullfinch, who was a kind of generic scientist/inventor, while Irene’s father was an astronomer. Fossil Cave was the first Danny Dunn book I read (although it was the sixth in the series). In the story they discovered a dinosaur skeleton buried in a nearby cave using what was essentially a portable CT scanner. I was enthralled (the fact that I totally had a crush on Irene probably helped), and immediately checked out all the Danny Dunn books I could find. I eventually found and read six of the 15 books in the series. The Nine Planets, by Franklyn M. Branley

The Danny Dunn books were a series of science-themed children’s novels in which three children (Danny Dunn, Irene Miller, and Joe Pearson) became involved in various science and technology adventures. Danny’s mother was a live-in housekeeper for Professor Bullfinch, who was a kind of generic scientist/inventor, while Irene’s father was an astronomer. Fossil Cave was the first Danny Dunn book I read (although it was the sixth in the series). In the story they discovered a dinosaur skeleton buried in a nearby cave using what was essentially a portable CT scanner. I was enthralled (the fact that I totally had a crush on Irene probably helped), and immediately checked out all the Danny Dunn books I could find. I eventually found and read six of the 15 books in the series. The Nine Planets, by Franklyn M. Branley This was a non-fiction science book, again aimed at children. I was already interested in dinosaurs from the Childcraft books. But upon discovering that they were extinct it occurred to me that maybe they were only extinct on Earth, and could still be living on other planets (give me a break, I was in 2nd grade!). I checked out and read The Nine Planets in order to find out.Some of the concepts in The Nine Planets were a bit beyond me at that age, but it was enough to confirm that dinosaurs were unlikely on other planets, and to get me interested in astronomy. That interest has continued, and I didn’t choose between astronomy, paleontology, and field biology until I was in college. All About Whales, by Roy Chapman Andrews

This was a non-fiction science book, again aimed at children. I was already interested in dinosaurs from the Childcraft books. But upon discovering that they were extinct it occurred to me that maybe they were only extinct on Earth, and could still be living on other planets (give me a break, I was in 2nd grade!). I checked out and read The Nine Planets in order to find out.Some of the concepts in The Nine Planets were a bit beyond me at that age, but it was enough to confirm that dinosaurs were unlikely on other planets, and to get me interested in astronomy. That interest has continued, and I didn’t choose between astronomy, paleontology, and field biology until I was in college. All About Whales, by Roy Chapman Andrews When I first read this book I had no idea that Roy Chapman Andrews was one of the most famous of all paleontologists. Year later, while in graduate school I saw a copy in a library discard sale and I finally made the connection. Andrews’ children’s books are fun reads. All About Whales has some chapters that go into a fair amount of detail about whale skeletal anatomy and others in which he talks about accompanying whalers on a hunt and having to fight off sharks after ending up in the water. This book actually influenced me twice; as a child it reinforced the idea of science as an adventure in learning, and as an adult it helped me realize the influence a scientist could have by making their research accessible to everyone.By the end of the 2nd grade I was completely hooked on science. I read every paleontology and astronomy book I could find in my school’s library and the public library in Vinton (we started driving out there every few weeks). This broadened my reading selection considerably. The Lost World, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

When I first read this book I had no idea that Roy Chapman Andrews was one of the most famous of all paleontologists. Year later, while in graduate school I saw a copy in a library discard sale and I finally made the connection. Andrews’ children’s books are fun reads. All About Whales has some chapters that go into a fair amount of detail about whale skeletal anatomy and others in which he talks about accompanying whalers on a hunt and having to fight off sharks after ending up in the water. This book actually influenced me twice; as a child it reinforced the idea of science as an adventure in learning, and as an adult it helped me realize the influence a scientist could have by making their research accessible to everyone.By the end of the 2nd grade I was completely hooked on science. I read every paleontology and astronomy book I could find in my school’s library and the public library in Vinton (we started driving out there every few weeks). This broadened my reading selection considerably. The Lost World, by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle I believe I first read Doyle’s famous book after checking a copy out of the public library. I found myself wishing for the characters to have more encounters with the dinosaurs so I could read more detailed descriptions. It bothered me greatly that there was almost no description of the aquatic creatures in the Central Lake. It’s probably also informative that I found the scientists vastly more interesting than either Roxton or Malone and that, while I found Professor Challenger impressive and amusing, the character I most identified with was Professor Summerlee.Starting around 1980 I found another source of books; flea markets. Paperback books and magazines would generally sell for somewhere between a nickel and a quarter, and while rural Virginia flea markets were not exactly hotbeds of scientific literature, there were some things to choose from.For many decades Isaac Asimov wrote a monthly science column for the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. A subscription to F&SF was way out of my financial league, but many of Asimov’s essays were republished in paperback compilations; these would sometimes turn up at the flea markets, and I ended up with perhaps 8-10 different compilations. While the majority of these essays were on astronomy topics, Asimov was a biochemist and an eclectic writer, and the topics often involved chemistry, biology, physics, and science history.

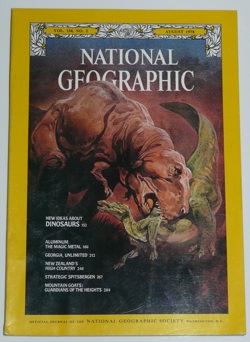

I believe I first read Doyle’s famous book after checking a copy out of the public library. I found myself wishing for the characters to have more encounters with the dinosaurs so I could read more detailed descriptions. It bothered me greatly that there was almost no description of the aquatic creatures in the Central Lake. It’s probably also informative that I found the scientists vastly more interesting than either Roxton or Malone and that, while I found Professor Challenger impressive and amusing, the character I most identified with was Professor Summerlee.Starting around 1980 I found another source of books; flea markets. Paperback books and magazines would generally sell for somewhere between a nickel and a quarter, and while rural Virginia flea markets were not exactly hotbeds of scientific literature, there were some things to choose from.For many decades Isaac Asimov wrote a monthly science column for the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction. A subscription to F&SF was way out of my financial league, but many of Asimov’s essays were republished in paperback compilations; these would sometimes turn up at the flea markets, and I ended up with perhaps 8-10 different compilations. While the majority of these essays were on astronomy topics, Asimov was a biochemist and an eclectic writer, and the topics often involved chemistry, biology, physics, and science history. The other thing that frequently showed up at the flea markets were back issues of National Geographic. Almost every issue would include at least one article related to science in some way, and I would dig through boxes picking out the ones that looked most promising (at 5 or 10 cents each, I could only afford a few at a time). Then one year, around 1980, I hit the jackpot. Someone had been selling a huge collection of Nat Geos, perhaps 150-200 issues. They were asking 25 cents for each one, which was out of my price range. But at the end of the day, they took everything they hadn’t sold (nearly all of them) and threw them in the dumpster. My sister spotted them as we were leaving, and Mom stopped the car while I climbed in the dumpster and pulled out 10 boxes of Nat Geos.Four National Geographic issues in particular always stood out for me.August 1978New Ideas about Dinosaurs, by John Ostrom

The other thing that frequently showed up at the flea markets were back issues of National Geographic. Almost every issue would include at least one article related to science in some way, and I would dig through boxes picking out the ones that looked most promising (at 5 or 10 cents each, I could only afford a few at a time). Then one year, around 1980, I hit the jackpot. Someone had been selling a huge collection of Nat Geos, perhaps 150-200 issues. They were asking 25 cents for each one, which was out of my price range. But at the end of the day, they took everything they hadn’t sold (nearly all of them) and threw them in the dumpster. My sister spotted them as we were leaving, and Mom stopped the car while I climbed in the dumpster and pulled out 10 boxes of Nat Geos.Four National Geographic issues in particular always stood out for me.August 1978New Ideas about Dinosaurs, by John Ostrom By the time I obtained this issue, I had read dozens of children’s books on dinosaurs. I also loved watching Land of the Lost on Saturday mornings. All of these sources portrayed a very consistent image of dinosaurs as little more than giant, spiky lizards that hung out in swamps all day (although the Tyrannosaurus in Land of the Lost was remarkably quick and agile). In other words, the stuff I was reading in the 1970’s was based on the science of the 1950’s, or even earlier. Ostrom’s article was the first thing I had read that showed paleontology as a dynamic science that was discovering more than just new species. Some of the things in my books could be wrong, and there were still lots of new things to discover.December 1976The Imperiled Giants, by William Graves and Exploring the Lives of Whales, by Victor SchefferJanuary 1979Humpbacks: The Gentle Giants, by Sylvia Earle and Humpbacks: Their Mysterious Songs, by Roger Payne

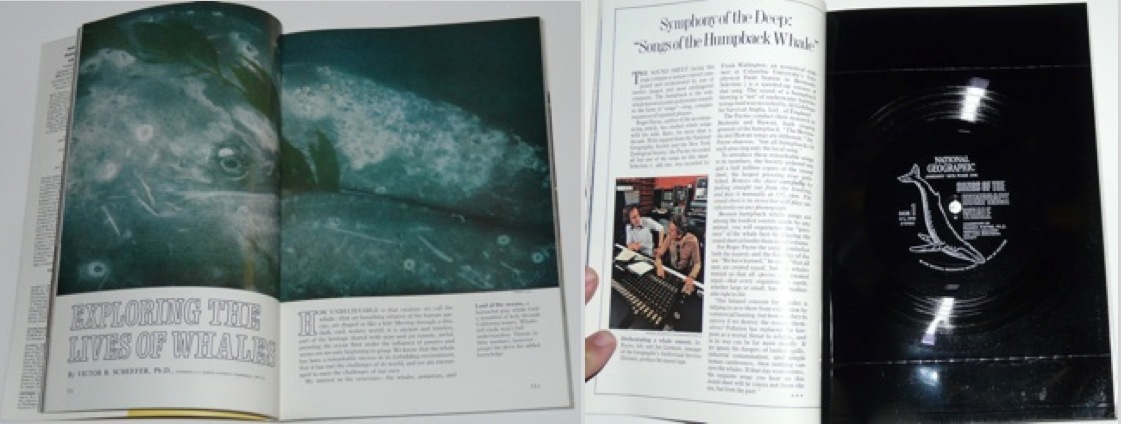

By the time I obtained this issue, I had read dozens of children’s books on dinosaurs. I also loved watching Land of the Lost on Saturday mornings. All of these sources portrayed a very consistent image of dinosaurs as little more than giant, spiky lizards that hung out in swamps all day (although the Tyrannosaurus in Land of the Lost was remarkably quick and agile). In other words, the stuff I was reading in the 1970’s was based on the science of the 1950’s, or even earlier. Ostrom’s article was the first thing I had read that showed paleontology as a dynamic science that was discovering more than just new species. Some of the things in my books could be wrong, and there were still lots of new things to discover.December 1976The Imperiled Giants, by William Graves and Exploring the Lives of Whales, by Victor SchefferJanuary 1979Humpbacks: The Gentle Giants, by Sylvia Earle and Humpbacks: Their Mysterious Songs, by Roger Payne For many years National Geographic seemed to have a special relationship with whale research, and they published numerous articles on whales in the 1970’s. These two issues really stood out for me. One presented an overview of all different species of whales, and I realized that even among living animals there was much greater diversity than I had realized. The other focused on humpback whales, and is the issue that included the famous whale song record as a plastic insert (I think this is the only record Nat Geo ever released). This got into some of the nitty-gritty of whale research, and emphasized that a lot things were still unknown. I should emphasize that these articles (and Andrews’ book) didn’t directly lead to me working on fossil whales, but they probably helped me make that transition more easily years later.January 1980What Voyager Saw: Jupiter’s Dazzling Realm, by Rick Gore

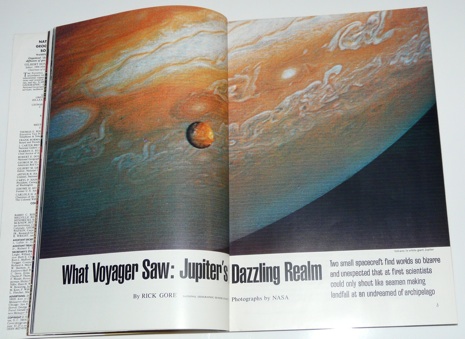

For many years National Geographic seemed to have a special relationship with whale research, and they published numerous articles on whales in the 1970’s. These two issues really stood out for me. One presented an overview of all different species of whales, and I realized that even among living animals there was much greater diversity than I had realized. The other focused on humpback whales, and is the issue that included the famous whale song record as a plastic insert (I think this is the only record Nat Geo ever released). This got into some of the nitty-gritty of whale research, and emphasized that a lot things were still unknown. I should emphasize that these articles (and Andrews’ book) didn’t directly lead to me working on fossil whales, but they probably helped me make that transition more easily years later.January 1980What Voyager Saw: Jupiter’s Dazzling Realm, by Rick Gore I can’t remember the Voyager spacecraft being launched, and in fact I don’t remember seeing a single news broadcast about their encounters (although there must have been some). So when I read the Nat Geo summary of the Jupiter encounters it was completely new to me. It seemed like practically everything I had read about the Solar System was terribly incomplete if not outright wrong. I also read that the Voyager probes were still going, with more encounters yet to come. I couldn’t wait!I can’t emphasize enough the impact Voyager had on me. After Jupiter revealed what Voyager could find, it was like getting science on a schedule. All we had to do was wait for Voyager to reach Saturn, and new discoveries were all but guaranteed. It seemed like all the efforts of all the scientists through the centuries had barely scratched the surface, and for me, emphasized science as an ongoing endeavor, not a body of facts.My interest in science was no secret among my family by the time I was in upper elementary school. Several of my relatives really supported this, including my parents, my grandmothers, and some of my father’s sisters. Around 1980, my Aunt Virginia joined some type of “Book of the Month” club. For several years, she used her club credits to buy me a science book each Christmas.

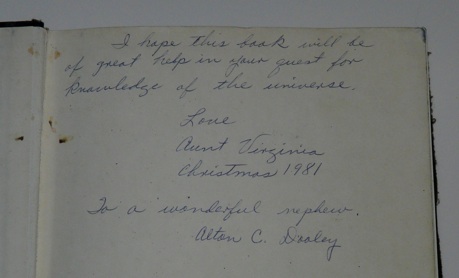

I can’t remember the Voyager spacecraft being launched, and in fact I don’t remember seeing a single news broadcast about their encounters (although there must have been some). So when I read the Nat Geo summary of the Jupiter encounters it was completely new to me. It seemed like practically everything I had read about the Solar System was terribly incomplete if not outright wrong. I also read that the Voyager probes were still going, with more encounters yet to come. I couldn’t wait!I can’t emphasize enough the impact Voyager had on me. After Jupiter revealed what Voyager could find, it was like getting science on a schedule. All we had to do was wait for Voyager to reach Saturn, and new discoveries were all but guaranteed. It seemed like all the efforts of all the scientists through the centuries had barely scratched the surface, and for me, emphasized science as an ongoing endeavor, not a body of facts.My interest in science was no secret among my family by the time I was in upper elementary school. Several of my relatives really supported this, including my parents, my grandmothers, and some of my father’s sisters. Around 1980, my Aunt Virginia joined some type of “Book of the Month” club. For several years, she used her club credits to buy me a science book each Christmas. Cosmos, by Carl Sagan

Cosmos, by Carl Sagan I read the book Cosmos before seeing the video series of the same name. Sagan did a great job emphasizing the depth of geologic time and the scale of the universe. He also frequently paid homage to early scientists. I was particularly taken with his description of Eratosthenes’ calculation of the circumference of the Earth, using nothing more than two sticks, careful observation, and relatively simple math. The fact that such a major discovery could be made so simply made my goal of becoming a scientist seem that much more attainable.Another important concept in Cosmos was the distinction between science and pseudoscience. Remember that most of my resources were coming from school libraries and flea markets. Other than a few trips to the doctor, by the time Cosmos was published in 1980 (when I was 11) the only people I had ever met with college degrees were my elementary school teachers; I had never met anyone with a science degree. That made it very difficult to evaluate the other books I would find in the libraries and flea markets, on astrology, the Bermuda Triangle, alien visits to Nazca, or Bigfoot and Nessie, among others. Admittedly, I had begun to have doubts about some of these things (“Why did the characteristics of my astrological sign seem to match me so poorly? With so many people looking for Nessie in a small lake, why couldn’t anyone get a good picture? Couldn’t the Navy TBMs just have gotten lost and run out of gas?”). So far as I know, Cosmos was the first popular science book that took on pseudoscience en masse and tried to define how science was different.There were many other influences for me along the way, and I’m sure I’ve since forgotten many of them. But these books all stand out from my early childhood. It’s not that all of them contained the best scientific information, even for the time (how much accurate science was there in Danny Dunn and the Fossil Cave, really?). But all of them opened my mind to new concepts, and led me to seek out additional sources of information. As far as I can determine, these books were the genesis of and the major guiding influences in my interest in science.

I read the book Cosmos before seeing the video series of the same name. Sagan did a great job emphasizing the depth of geologic time and the scale of the universe. He also frequently paid homage to early scientists. I was particularly taken with his description of Eratosthenes’ calculation of the circumference of the Earth, using nothing more than two sticks, careful observation, and relatively simple math. The fact that such a major discovery could be made so simply made my goal of becoming a scientist seem that much more attainable.Another important concept in Cosmos was the distinction between science and pseudoscience. Remember that most of my resources were coming from school libraries and flea markets. Other than a few trips to the doctor, by the time Cosmos was published in 1980 (when I was 11) the only people I had ever met with college degrees were my elementary school teachers; I had never met anyone with a science degree. That made it very difficult to evaluate the other books I would find in the libraries and flea markets, on astrology, the Bermuda Triangle, alien visits to Nazca, or Bigfoot and Nessie, among others. Admittedly, I had begun to have doubts about some of these things (“Why did the characteristics of my astrological sign seem to match me so poorly? With so many people looking for Nessie in a small lake, why couldn’t anyone get a good picture? Couldn’t the Navy TBMs just have gotten lost and run out of gas?”). So far as I know, Cosmos was the first popular science book that took on pseudoscience en masse and tried to define how science was different.There were many other influences for me along the way, and I’m sure I’ve since forgotten many of them. But these books all stand out from my early childhood. It’s not that all of them contained the best scientific information, even for the time (how much accurate science was there in Danny Dunn and the Fossil Cave, really?). But all of them opened my mind to new concepts, and led me to seek out additional sources of information. As far as I can determine, these books were the genesis of and the major guiding influences in my interest in science.